My German grandmother lived in Berlin during the war and saw through all but one of the Nazis. Minna Niemann poured scorn on the man she called Herr Hitler and lambasted his odious deputies: “That Goebbels is a gangster!” she would declare indignantly. Within four walls, the woman who was adored by all who knew her carried out private acts of resistance. On the birth of her fourth child, she was awarded the Mutterkreuz (Mother’s Cross) to mark her achievement in producing Aryan offspring. She threw her medal straight into the bin. Every winter, the family was sent a candle that was meant to be lit in a shrine, a kind of Nazi alternative to Christmas. Minna expressed her contempt and loathing for this affront to her Lutheran faith by disposing of it at once.

Men in dirty striped uniforms came to the house, bringing furniture they had made, fitting bunk beds for the children, building an air-raid shelter and carrying out general repairs. These were concentration camp inmates from Sachsenhausen and its satellite camps. Though it was strictly verboten, Minna spoke to them and brought coffee and cake. My dad remembered the poor, half-starved men telling her how much they liked coming to their house.

My grandmother’s antipathy towards the regime boiled over in the last months of the war, at a time when the merest whiff of dissent saw offenders hanged from lampposts in the streets. She spoke out often, and loudly. Her daughter Anne wrote a worried “What are we going to do about Mother?” letter to her boy soldier brother, Dieter. The family began to fear that their phone was tapped.

For all her evident opposition to the Nazis, there was one man who escaped Minna’s wrath and condemnation, her husband, Karl. Less than three years ago, I found out the truth about my grandfather – he was a committed member of the Nazi party, an SS officer, a manager of slave labour in Auschwitz, Dachau, Buchenwald and other concentration camps. How was it possible for my grandmother to live a life of glaring contradictions?

My grandmother, a seamstress, met Karl Niemann, a bank clerk, in the pied piper town of Hameln (Hamelin)in 1912. Their relationship would last 48 years, though it would be marked by long periods of separation. The first came in August 1914, when Karl went off to fight. Wounded and captured by the French, he remained in a prisoner of war camp until March 1920. Minna waited six years for her fiancé to return – they married the following year.

In the weeks after Minna gave birth to Anne, the couple’s first child, Karl brought home his wages in a wheelbarrow. Germany was in financial meltdown, with rampant hyperinflation. The economy recovered, and shortly after the birth of their son, Dieter, Karl took a job as an auditor in a private company and the family moved to Dortmund.

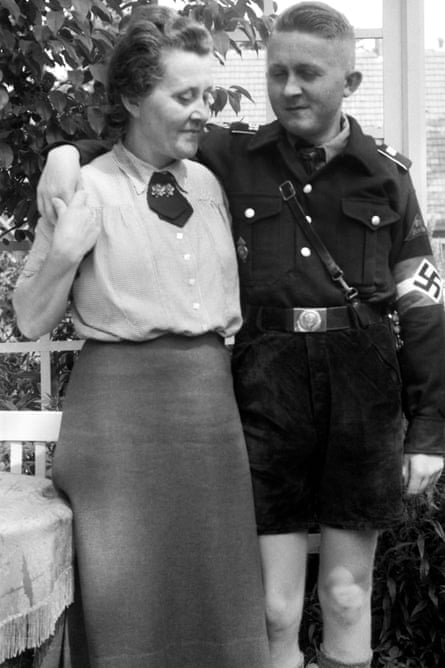

Three years later, in 1929, came the Wall Street crash. In the midst of soaring unemployment and pitched battles between factions on the right and left, Karl joined the Nazi Party, immediately becoming a minor official. In the year Hitler came to power, Minna, pregnant with my dad, was pictured with her uniformed husband, an Oliver Hardy lookalike wearing swastikas. There was nothing funny about a man who was under instructions to inform the Gestapo about people who showed suspect political views.

The couple had three young children to feed when Karl, the only Nazi in the company, fell out with his boss and was sacked. They were now in desperate straits. Their landlord knew an influential man who had gone to the same school as Karl and could perhaps find him a job. He happened to be Heinrich Himmler’s deputy.

I do not know what Minna thought of her husband going to work for the SS. Perhaps it was enough for her that he had a job again, and a fairly well-paid one at that. Karl went on ahead to Bavaria to be inducted into the SS, settle into his new post and find accommodation. Minna stayed behind with her children and wrote to Karl that Anne had a new friend and visited her often at home. The order came back – Anne was not to speak to Jews.

My uncle told me that his mother did not want him associated with the town where she took her family to live in early 1936: Dachau. She went to a hospital in the next town to make sure that he would not have Dachau on his birth certificate. My uncle was christened Ekart Josef, after Karl’s colleague (and presumably friend) Josef Spacil, a dubious character who made off with much of the Reich’s gold bullion at the end of the war.

Initially, Karl worked as an auditor for an SS complex next door to the concentration camp, but his job morphed into managing slave labourers from the camp itself. SS officers and their families were expected to socialise freely. Minna went on day trips to the Alps with her husband’s colleagues and their wives.

A year before war broke out, Karl’s job relocated to Berlin and Minna brought the children to live on an estate purpose-built for SS families. She played the subordinate, domestic role that Hitler’s Germany demanded, an ideology that reduced women’s role to Kinder, Küche, Kirche (children, kitchen, church). Karl, meanwhile, had become a business manager for the SS, travelling through occupied Europe to inspect his concentration camp “factories”, undoubtedly witnessing scenes of unimaginable brutality.

How much of what he saw did he bring home to his wife? My dad remembered his father guarding an inner world: “He was very much his own man.”

As a child of 11, my dad witnessed – and remembered – a telling conversation between his parents. In April 1945, as Russians closed in on Berlin, the men in Karl’s office were redeployed with their families to the Alps. The entourage halted for two or three days at Dachau, sleeping in the bunks of former guards. My father watched as Karl and Minna looked out at a low building with tall chimneys. There was smoke rising from the chimneys. “You know what they’re doing there?” asked Minna. “They’re killing the Jews and burning the bodies.” Karl was quick in his denial: “No, they wouldn’t do that.”

“Yes, they would,” replied his wife. “Can’t you smell the flesh?”

So Minna knew, as many in Berlin did, something of what was happening in the Holocaust. Either she believed her husband didn’t know or she was testing his level of knowledge. When the family reached their dead end, an isolated lodge at the top of an Alpine valley, Minna said bitterly: “Look where your Herr Hitler has got us now.”

The day after Germany surrendered, American soldiers came for Karl: he served three years’ internment in former PoW camps. Minna took her children back to Hameln, where she proceeded to delete the past. All of the photographs of old Nazis disappeared. She hung up a picture of her dead soldier son, Dieter, after carefully obliterating the SS flashes on his uniform with a pencil. And, in common with millions of other Germans, they did not talk about what had happened.

None of the family had ever seen the papers from Karl’s tribunal until I tracked them down in a Hannover archive two years ago. They drew out the remarkable story of the man who came to dinner. My dad recalled his mother saving the family’s meat ration to share with a thin guest who came on Sundays late in the war. He was a former concentration camp inmate, whom Karl had had released from Dachau to work for him. And, it transpires, there were others. Karl emerged as a man of complex motivations, fixing deals with the Gestapo to have inmates freed. Some of those inmates testified in his favour at his tribunal. My dad had always clung to a story, garbled in family mythology, that his father was “the only one who treated inmates like human beings”.

Even so, the judge condemned Karl for expressing no remorse about exploiting people reduced to slavery. I had assumed that the broken man who returned from prison was overwhelmed with guilt. Was that the case? I simply don’t know.

As for Minna, the historian Katharina von Kellenbach said of the wives of Holocaust perpetrators: “We can safely assume that many of them knew enough of their husbands’ assignments to conclude that they would be better off not knowing more of the sordid details.” And so I imagine the couple lived out the rest of their lives with a giant barbed wire elephant in the room.

I cannot question my grandmother, who died before I was born. I would love to believe that her little acts of resistance and kindness within a Nazi enclave represented some kind of heroism. But I have come to accept that, like millions of other Germans, she put her own family’s welfare first and shut her eyes and ears to what was going on outside her home. My dad and uncle said their parents were mutually devoted to the end. But did Minna ever look at Karl and wonder about the dark things that remained in his head?

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion