-

Introduction

‘A is for Adolf’ exhibition in situ outside UNESCO headquarters in Paris, 27 January 2016 The following is an online version of an exhibition on display at the UNESCO headquarters in Paris from 25 January 2016 to 28 February 2016. This exhibition was chosen in accordance with the theme of the 2016 International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust, (observed 27 January): “From Words to Genocide: Antisemitic Propaganda and the Holocaust.”

The original 2011 exhibition A is for Adolf showed the Library’s unique collection of Nazi children’s books, games and toys to the public for the very first time. This propaganda collection’s history dates back to the early work of the Library’s founder, Dr Alfred Wiener, a German-Jewish refugee. At the time when this collection was first begun, Wiener and several colleagues were based at the Jewish Central Information Office in Amsterdam, working to counter Nazi propaganda and to raise global awareness of the true nature of Hitler’s regime. The Wiener Library’s propaganda collection still has an important role to play today, providing a rare insight into the complex relationship between the Nazi regime and those it sought to indoctrinate. We are grateful to the Ernest Hecht Charitable Foundation for their grant which enables us to acquire new rare items relating to the indoctrination of children in the Nazi era.

The display has four themes: School, Experiences of Jewish Children, The Hitler Youth and Beyond School. Each theme displays images of original materials held by the Wiener Library in London, accompanied by explanatory texts. The aim is to show various ways that the Nazis tried to influence German children both at school and in other contexts. Nazi propaganda sought to shape every aspect of young people’s thoughts, especially their perception of the self and the ‘other,’ the ‘German’ and the ‘Jew.’

The Wiener Library is pleased to have been able to contribute to UNESCO’s activities marking the International Day of Commemoration of the Holocaust in 2016.

-

-

Group of young girls giving the ‘Hitler Salute’ during a Nazi parade 1930s

From Children of SS, 1976; Source: USIS; Image WL7260Introduction

From the earliest stage of the development of the Nazi movement, the youth in Germany were seen as a crucial political target by leading Nazi propagandists.

After Hitler’s rise to power, National Socialist ideology permeated all aspects of German society. Gradually the law and all state organisations were brought into line with Party beliefs. The Nazis created National Socialist alternatives to existing organisations, such as trade unions and sports associations. Nazism even transformed children’s lives: National Socialist rituals were incorporated into school routines and the new doctrine shaped teaching and school books.

-

School

A class in uniform in Nazi Germany, late 1930s

From Nazi Culture, 1966; Source: NSDAP Standarten Kalender 1939; Image WL5714

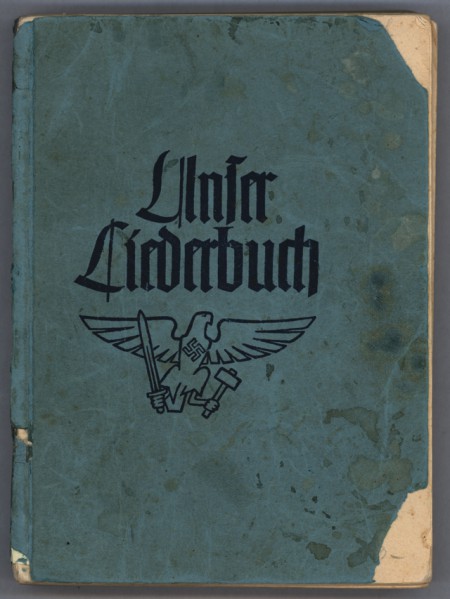

Nazi picture book for children in the form of a horse, containing patriotic songs / WL1242 Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 changed the world for children as well. Before long, schools were adapting to the doctrines of the new regime, with class instruction moving in step with National Socialist ideology. National Socialist ideas began to gradually alter school routine. Like on the street, Nazism was also omnipresent in the schools: portraits of Hitler and swastika signs were visible in the schools, classrooms and textbooks. There were also Nazi flags in the school yards.

Left: “Germany, Germany above all/Above all in the world/When always, for protection, we hold together as brothers/From the Maas to the Memel/From the Etsch to the Belt/Germany, Germany above all/Above all in the world”

-

School

In the early years of the regime much of the organisation and teaching within schools was allowed to remain mostly unchanged, but pressure to adopt Nazi ideas and practices grew over time. A central focus of National Socialist pedagogy was the ‘leader principle’, which required submission to authority and a culture of hero worship. In general, teaching in Nazi Germany showed a very strong bias towards the deed rather than towards thought.

-

Westermanns Handwriting Guide for Greater Berlin: first reading book for children Illustrator: Eugen Osswald Author: Otto Zimmermann 1935 / Image WL1027 -

Westermanns Handwriting Guide for Greater Berlin: first reading book for children Illustrator: Eugen Osswald Author: Otto Zimmermann 1935 / Image WL14637

-

-

The ABC of Race

Author: Franz Lüke

1935

Image WL14640School

Introduction to Genetics, Genealogy, Ethnology and Population Policy Author: L. Trinkwalter 1934 / WL14640 Indoctrination within schools covered a number of issues and paved the way for the youth’s acceptance of Nazi policies: among them, the superiority of one race over the other, the ‘leader principle’, the ‘blood and soil’ dogma, and the ‘a people without space’ tenet.

Below: From a textbook discussing ‘racial sciences’. The vast majority of the ‘race science’ taught in schools was later disproven, but at the time the Nazis saw it as an ‘objective’ and ‘modern’ way to reinforce their ideas about society.

-

School

Arithmetic book for elementary schools: Districts North and South Westphalia. Editor: Adolf Schiffner, 1941

Image WL3044The Ministry for Education stipulated, for example, that mathematical problems should be based on the tenets of ‘race science’ – and it is in maths’ school books of the period that the Nazi ideology shows itself most clearly.

Right: The title of the diagram reads ‘What does it cost to care for people with hereditary illnesses?’

When teaching history, teachers had to emphasise the importance of race for the course of human history. History was to be explained as a struggle of races; the success of one race over another was to be explained by the ‘natural laws of race’ and the Northern races were presumed to be naturally superior. All Western culture was to be presented solely as an achievement of the Northern races.

Below: ‘Germany’s Neighbours in Arms’ Educational rotating disc used to teach children about German military strength relative to other European countries. The reverse side of the disc shows a student timetable.

-

-

From a copy of a school book which belonged to Doris Kahn, a Jewish pupil in Cologne, 1933-1934. The contents of the book were dictated by the teacher and consist of notes on the racial characteristics of the various Germanic ethnic groups.

Image WL 14635Experiences of Jewish Children

As early as 25 April 1933 only a restricted number of Jews were admitted to German universities and schools. As long as their numbers did not exceed a certain level, Jewish pupils were still allowed to attend state schools. Five years later, on 15 November 1938, Jewish children were banished by law from attending state and non-Jewish private schools altogether. On a local level, even the right of Jewish children to attend Jewish schools was often restricted.

Below: From a copy of a school book which belonged to Doris Kahn, a Jewish pupil in Cologne, 1933-1934. The contents of the book were dictated by the teacher and consist of notes on the racial characteristics of the various Germanic ethnic groups.

-

The Poisonous Mushroom / Illustrator: Phillip Ruprecht, Author: Ernst Hiemer, c.1938 Image WL7214 Experiences of Jewish Children

Illustration from the book Race as a Law of Life / Author: Richard Eichenauer, 1934 / WL3998 Very soon, those German teachers who supported the Nazis or had been converted to Nazism began to develop new daily rituals and routines. As many as 32 per cent of teachers became Nazi Party members, and many would wear their uniform to school. All teachers had to swear an oath of allegiance to Hitler and teach in accordance with Nazi ideas and values. All Jewish teachers were dismissed, as were teachers who refused to support the Nazi Party’s ideals.

Right: ‘The Jewish nose is bent at its tip. It looks like a number six’

-

A school project by a non-Jewish girl, Gerda Nabe, depicting a family tree defining who was Jewish according to the Nuremberg Laws.

Image WL14584

Der Pudelmopsdackelpinscher und andere besinnliche Erzählungen / Author: Ernst Hiemer, 1940 / WL14645 Experiences of Jewish Children

Pupils were to be taught how they themselves had the duty to adhere to the principles of eugenics when they got married and had children. They were also taught of the importance of avoiding hereditary diseases among the German people. Like anybody else, children want to belong and not be marked as outsiders. After 1933 this was no longer possible for Jewish children.

Below: Front page of a story book about a ‘crossbred’. The story was intended to discourage racial intermarriage.

-

Trust no fox on the green heath and no Jew on his oath: a picture book for big and small / Author: Elvira Bauer, 1936

Image WL992Experiences of Jewish Children

Anti-Jewish restrictions affected the lives of Jewish children at home, at school and at play. Jewish children had to leave public schools and attend Jewish schools, until these, too, were closed. Exclusion from German society was only the beginning: the persecution of Jewish children and their parents steadily mounted over time.

Below: “In E. the 64-year-old very renowned lawyer F. was arrested and the entire furnishings of his villa were smashed to pieces. Later hundreds of children were led through the house for days by adults, perhaps teachers, apparently to show them in what manner revenge is being taken on the ‘enemies of the people’.” Report of an eyewitness to the November Pogrom, author unknown, Doc 1375/1 [B120], Wiener Library.

SA-man and children look on as piled-up synagogue furnishings are burned during the November Pogrom, 1938 / WL870 -

The Hitler Youth

The hearts of Germany’s children belong to him. From a Nazi propaganda photography book (Deutschlands Kinderherzen gehoeren mir), 1935. Image WL4082 The Hitler Youth was organised like a military unit, its members, trained in drills and shooting, wore uniform. The organisation offered a number of possibilities to rise in rank; this was also rewarded by cordons and badges which were worn on the uniform, thereby offering additional incentives to perform in accordance with ideology.

-

The Hitler Youth

The Hitler Youth was made up of local cells, with its biggest annual gathering usually taking place during the party rallies at Nuremberg.

-

Klaus, the Hitler Youth / Authors: Bernhardt and Ilse Wende, c.1933 / WL4057 -

The nations youngest drummer boys,

Propaganda picture taken at a Nazi party rally.

From Adolf Hitler Sammelwerk Nr 15; Image WL 8772

-

-

The Hitler Youth

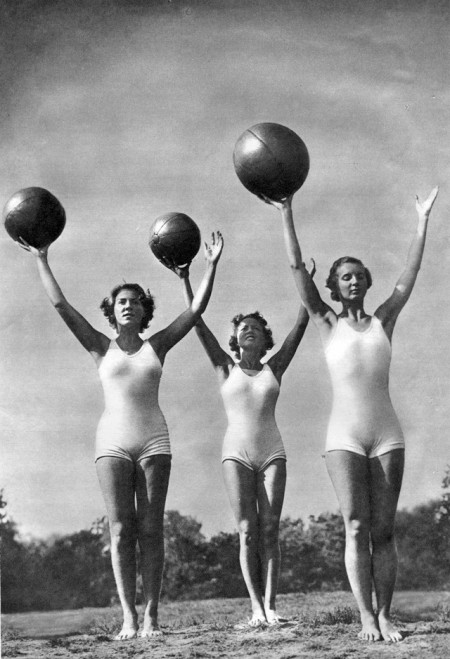

The Bund Deutscher Mädel (League of German Girls) was part of the Hitler Youth and was aimed at indoctrinating all girls and young women between ages 10 and 21. As with the Hitler Youth, its pedagogical goal was to educate girls according to Nazi ideology which, for girls, meant to prepare them for their future role as ‘German mothers’.

-

Women from the BDM (League of German Girls) during a gymnastic performance.

Image WL8 -

Ulla, a Hitler girl / Author: Helga Knoepke-Joest, c.1933 / WL8

-

-

The Hitler Youth

They carry the flags to Nuremberg. From a 1938 Nazi propaganda photography book, Jugend und Heimat.

Image WL4012Membership of the Hitler Youth was promoted through a variety of incentives such as hikes and camps. As well as activities offering adventure in the outdoors, Hitler Youth activities included marching bands and amateur theatricals. Strong emphasis was placed on the group experience. Events such as seasonal celebrations were aimed at enforcing a spirit of community.

-

-

The Hitler Youth

Hitler Youth ‘duty’ was usually performed twice a week, always on Saturdays, but often also on Wednesdays. Those between 10 and 14 years old joined the junior branch ‘Jungvolk’ were known as ‘Pimpfe’. In order to be allowed to wear the Hitler Youth pocket knife and the shoulder strap, aspirants had to take an exam which included physical tests and, at times, the biography of Adolf Hitler. Boys between 14 and 18 were organised in the Hitler Youth proper.

-

Two members of the Hitler Youth with a swastika flag. From a 1935 Nazi propaganda publication, Jugend um Hitler.

Image WL4100 -

Colouring book with Hitler Youth pictures. These figures were supposed to be coloured and cut out to create a cardboard scene / WL4122

-

-

Beyond School

Children became well acquainted with Nazi symbols from a very early age. The swastika symbol, the marching Hitler Youth, or SA men in uniform could be found in painting and colouring books and were depicted on other toys. Racial doctrine was also introduced at an early age and found its way into picture and painting books.

-

Mother, tell me about Adolf Hitler! / Author: Johanna Haarer, 1939 -

My Book for Looking, Drawing, Reading and Writing / Author: Hans Brückl, 1941 / WL4068

-

-

Beyond School

The swastika gradually became an ever-present image in the lives of German schoolchildren, but to many its exact meaning remained mysterious. The Nazis strove to encourage children to draw connections between this symbol and the values of the Third Reich, and above all with the personality of its Leader. Nazi card games also built on Germany’s strong military traditions and linked Hitler to a tradition of German war heroes.

-

Adolf Hitler block puzzle. The aim of this game was to rearrange letters spelling Hitler into the shape of a swastika / WL4042 -

Adolf Hitler block puzzle. The aim of this game was to rearrange letters spelling Hitler into the shape of a swastika / WL7702 -

The game is played by collecting four-card sets. One set showed four examples of Hitlers leisure pursuits.

Image Fuhrer Quartett

-

-

Jews Out!, Antisemitic board game

c.1938 Image WL14634Beyond School

“Juden Raus!” is probably the most infamous German anti-Semitic board game. The purpose of the game is that every player tries to remove ‘Jews’ from society, by collecting them in areas outside of the city walls drawn on the board. The ‘Jew’ is represented by a yellow hat with a drawing of a stereotypical Nazi image of a Jew. The players play with representations of the German police. The game’s tagline was: ‘The topical and outstandingly jolly multiplayer game for grown-ups and children’.

-

Beyond School

Some teachers used antisemitic books as reading material in their classes, and parents were also encouraged to use such books in the home. The book shows scenes from everyday life portraying Jews in a negative light. The narrative in The Poisonous Mushroom is loosely held together by the story of Franz, a young boy who is warned by his mother of mushrooms that appear good but are actually dangerous. In the book the poisonous mushroom clearly stands as a metaphor for the Jews.

-

Trust no fox on the green heath and no Jew on his oath: a picture book for big and small / Author: Elvira Bauer, 1936

Image WL7030 -

The Poisonous Mushroom / Illustrator: Phillip Ruprecht Fips, Author: Ernst Hiemer, c.1938 / WL10

-

-

Beyond School

Playtime as well as school was permeated by Nazi propaganda. Games and toys were used to help bring up children in the spirit of Nazi ideology and to orient them towards the ‘Führer’ and the Nazi party.

Below: Nazi war hero Lieutenant-Commander Joachim Schepke showing a model of a German submarine to Horst Plenk, son of the celebrated skier Tony Plenk.

-

Westermanns Handwriting Guide for Greater Berlin: first reading book for children / Illustrator: Eugen Osswald, Author: Otto Zimmermann, 1935

Image WL4067 -

The big and the small submarine sailor / French language edition of magazine Signal, April 1941 / WL4110

-

A is for Adolf: Teaching German Children Nazi Values

Exhibition Type: Online Exhibition