(click to enlarge photos)

In 1919, the California candy maker Pig’N Whistle opened in Seattle what it advertised in the Times as “the largest investment in a confectionary business which has ever been made anywhere in the world.” A year after Frederick and Nelson moved out, the block-long Rialto Building was ready for its new tenants, and the Pig got what had been the department store’s grand entrance on the west side of Second Avenue, centered between Madison and Spring Streets.

The elegant pig above the sidewalk was surely both big and dear. And it moved. Outlined in lights, two of its three hind legs were alternately lit to keep the animated leg kicking to the whistling flute the musical swine held to its snout with its hoofs. For thirteen years, and through the full length of Seattle’s “urban canyon” from the Smith Tower to the Washington Hotel, the dancing pig could be seen kicking time to its music.

The Pig N’ Whistle was packed from the start. Many of the stores nearby, like Meves Cafeteria, Rochester’s Men’s store, and Millers Luggage, promoted the pig as the landmark to find for their own services as well. Repeated society and club reports of lunch and dinner meetings at the Pig’N Whistle gave this maker of Viennese candies and “dainty sandwiches” frequent and free promotions in the local dailies.

Days after the California confectionary opened, King Bros. Co., another men’s store nearby, described the pig as “a thing of beauty, and we trust will be a joy forever to the people of our growing city.” Many years after it closed, Margaret Young, in a 1966 Times feature on the nostalgic lure of old Post Cards, professed to loving neon and wishing there were more of it, “but even more we miss something we never saw.” She meant this dancing pig. A victim of the Great Depression, the last listings for the Pig’N Whistle are from 1932.

Next week we will cross Second Avenue to the Palace Hip Theatre a half block north at Spring Street. The theatre, of course, treated the pig well, with many among it’s audiences consuming the Pig’N Whistle’s confections and dancing to its live music before and after the Hip’s shows.

WEB EXTRAS

Anything to add, Paul?

Merely two related features Jean – one from long ago, 1986, and the other nearly new from 2009 and so here its encore.

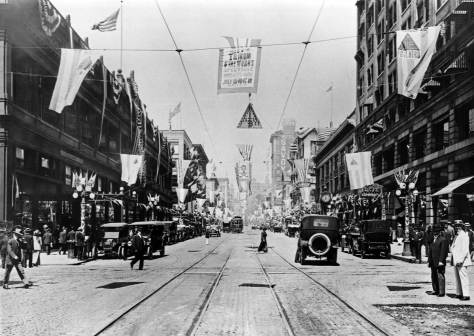

Looking northwest through the intersection of Madison Street (left to right) and Second Avenue to the Frederick and Nelson Department Store filling the half block on the west side of Second between Madison and Spring. Note above the cable car heading for the waterfront on the far left.

FREDERICK & NELSON DEPARTMENT STORE

(First appeared in Pacific, Oct. 28, 1986)

D. E. Frederick and Nels Nelson opened a second-hand store in Seattle in 1890. Soon they found it easier to buy unused merchandise than ferret out the old. So they discarded the nearly new trade, and in time their store became the largest and finest department store west of the Mississippi and north of San Francisco.

In 1897, in the first flush of the Klondike gold rush, the store was moved into the two center storefronts of the new Rialto building at Second Avenue and Madison streets. In 1906 the partners bought out the block, and Frederick & Nelson stretched their name the length of an entire city block – the Rialto block. This week’s historical scene shows Seattle’s first grand emporium during, or some time after, 1906.

Shopping at Frederick & Nelson was a different experience from today’s sometimes mad-rush shopping. At Frederick’s, you were invited to take classes, visit an art gallery, chat with friends over tea or just ride the hydraulic elevator. A big center room with a high ceiling for hanging tapestries and Persian rugs was a kind of sanctuary for consumption. Years later, you might not remember what was purchased but you would recall the experience of having really bought something significant – its aura.

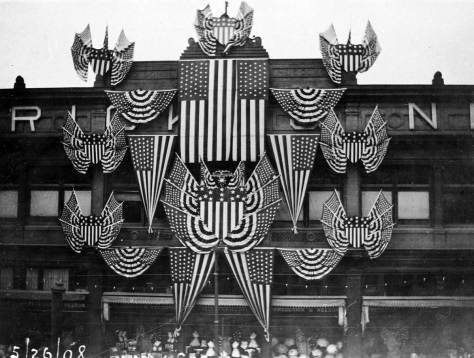

Above and below, scenes from a Golden Potlatch summer celebration (1911-1914).

This touch of class also was found in the elaborately decorated show windows along Second Avenue, and even in the street itself. Every morning, Frederick and Nelson’s 16 heavy teams of horses paraded from their stables down the length of Second Avenue.

Nelson died in 1906, but Frederick continued to make the right moves, including the one in 1918 that took him “out of town” – all the way north to Sixth Avenue and Pine Street. In 1929, Frederick retired to his home in the Highlands and sold his grand emporium to Marshall Field & Co. of Chicago. After his death 20 years later, his old golfing crony, 95-year-old Seattle Times columnist C.T. Conover, recalled Frederick as a kind of heroic capitalist saint who “left a record of straight shooting, fair play, honorable dealing, enlightened vision, common sense, civic enterprise, noble spirit and generous support of every worthy cause.”

=====

Above: A century ago – roughly – Engineer Leo Snow took this candid photograph of a single Native vendor set up at the northwest corner of Second Avenue and Madison Street. Thanks much to Dale and Eric Cooley for sharing this view. Below: Appropriately, for the contemporary repeat Jean Sherrard recorded Cassie Phillips, a Real Change salesperson, showing her fare at the same corner.

SIDEWALK SALES

(First appeared in Pacific, June 21, 2009)

Clearly the northwest corner of Second Avenue and Madison Street was good for sales both inside an out. In 1906 Frederick and Nelson’s expanded from its mid-block quarters in the block-long Rialto building to both corners, at Madison and Spring Streets. While the corner sign does not promote baskets it does list carpets and its sidewalk “competitor,” the basket vendor recorded here by amateur Leo Snow, also offers mats. Snow’s snapshot is wonderfully unique for its bright-eyed candor.

As confirmed by many other less lively photographs, including a 1911 postcard printed in “Native Seattle,” historian Col Thrush’s nearly new book from U.W. Press, this was a popular corner for both selling Native crafts and recording them doing it. Thrush’s postcard shows not one but three of what the postcard’s printed caption calls “Indian Basket Sellers” huddled at this corner.

When I began giving illustrated talks on Seattle history long ago I often included a native vendor slide in my show. Many were the times seniors in the audience would recall having been with their mother while buying a basket from Chief Seattle’s daughter, and often off this very sidewalk. Since the 86 year-old Princess Angeline died in 1896, this “princess claim” was more than unlikely, it was impossible – I gently explained. Still, however slanted, the memory of sidewalk meetings with Native Americans was still cherished in 1975. Do any readers still retain such memories in 2009?

Sometime after the farm boy Leo Snow got an engineering degree from Ohio University in 1902, he carefully folded a 3-piece suit in his duffle bag and hopped a freight train to Seattle. Scrubbed, adorned and qualified he was soon on the streets of this city looking for a job. In 1945 Leo D. Snow retired after working 37 years for Puget Power, and along the way took many more sparkling snapshots with his foldout Kodak.