The Elizabeth Peyton of the Palazzo Barbaro set, the painter John Singer Sargent had a way with white. From voluminous Bedouin robes to frothing Alpine streams, the sun-bleached marble steps of Santa Maria della Salute to the spotless cashmere shawl on a bloodless Boston socialite, the painter’s whites are perhaps the most socially nuanced in the history of watercolor. A show of nearly a hundred of his expert late watercolors (and a few middling oil paintings), mostly painted between 1901 and 1912, is well worth a visit.

Sargent was an inveterate expatriate: an Italian-born American who lived in London, he learned to paint in Paris. Best known for his massive oil portraits of society women, his watercolors capture what he saw during the travels he made after he had earned his fortunes as a painter and shuttered his studios at the start of the 20th century, when he was in his 50s. “Above all things, get abroad, see the sunlight, and everything that is to be seen,” he advised his friends back in Boston. Set free in an exotic place, he found himself at home. Here he’s rediscovered amateurism—painting his travels for love, rather than painting faces for money—and it shows. (The one exception here to his focus on landscapes over portrait painting is his The Cashmere Shawl from 1911, which has some of the showy ballroom drama of his famous 1884 Portrait of Madame X at the MFA in Boston.)

A technological innovation made Sargent’s peripatetic painting practice possible: watercolor boxes and tubes made for fast work outdoors. (As can be seen in a painting Sargent made of his sister, the top flap of a watercolor tin would open to become a palette; the paper was placed on a portable tripod made from a hiking stick.) Mountain Fire (1906-7) captures wispy smoke rising off mountains. A branch heavy with red pomegranates set against dense green leaves was a souvenir of Majorca.

Women are the stars of this show: giant pale bells of fabric among the Alpine landscape, all parasols, petticoats and sweaters. They are not sexy (Sargent was a “confirmed bachelor”) but sisterly travel companions, and they are incongruously and thoroughly American as they contemplate the Bridge of Sighs, dress up as Biblical characters, or laze on the perpetual vacation their class afforded them on the Greek island of Corfu.

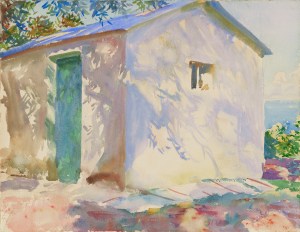

By using both opaque and translucent watercolors, Sargent achieved unusual effects, like pearly highlights made by dragging a loaded brush of wet paint across his translucent painted washes—techniques we associate more with Spanish oil painting than watercolor. His surfaces are so thick they sometimes crack. Tracks of graphite and areas of wax resist lie under these layers of paint. The paintings are light things, but they push technique. The white of paper is sometimes the bare highlight left from fast painting; sometimes the white is opaque watercolor brushwork.

Sargent could capture tone and mood, but he wasn’t a brilliant colorist. Chemical analysis shows that his colors were, surprisingly, often straight from the tube. His skies: straight cobalt; his

But put him in front of melon boats in Palestine and he gets the swell and movement of wind in waxed canvas sails. In White Ships (1908) the impastoed watercolor rigging is translucent above an awesome opaque anchor, and the white ships have bits of reflected pink and green on their hulls. You’ll get his American watercolor lightness: it’s the predecessor of Elizabeth Peyton’s pretty and ambivalent frosted lines. The neurasthenic Mrs. William James is a prim wash of blues and greens. He got around, too: Roman villas, Moroccan deserts and Florentine gardens. When the Brooklyn Museum bought most of these paintings in 1909, they were being sold as a group to conjure the classic grand tour.

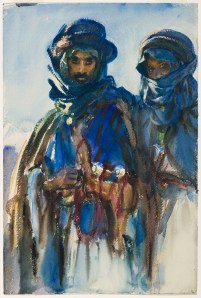

There are a handful of oil paintings in the show, most of them with exotic subjects like turbaned men. They are overworked and unexceptional compared with Sargent’s lightness and speed in the more casual medium. Co-curators Teresa A. Carbone of the Brooklyn Museum and Erica E. Hirshler of the MFA Boston have done well to focus on the watercolors.

In the exhibition’s last room, there are almost no people. Instead Sargent paints white marble quarries, Alpine streams and the white stone walls of Venetian palaces. You can almost hear the