In 2008, artist Kerry James Marshall was the subject of an oral history interview with the Smithsonian Institute where he recalled his childhood memory of the Watts riots of 1965. He remembered hearing sirens and seeing smoke, miles away coming from where he used to live in Nickerson Gardens. Over the course of the afternoon he started seeing people run by his home. At first there was one, then two or three, then dozens of people were running in the streets. As the chaos, looting and fires began to migrate from Avalon and 116th Street, the intensity of the confusion grew. Toward the end of the first evening of the rebellion, the sky was pitch black from a power outage and Marshall remembered seeing a Jack in the Box sign down the street.

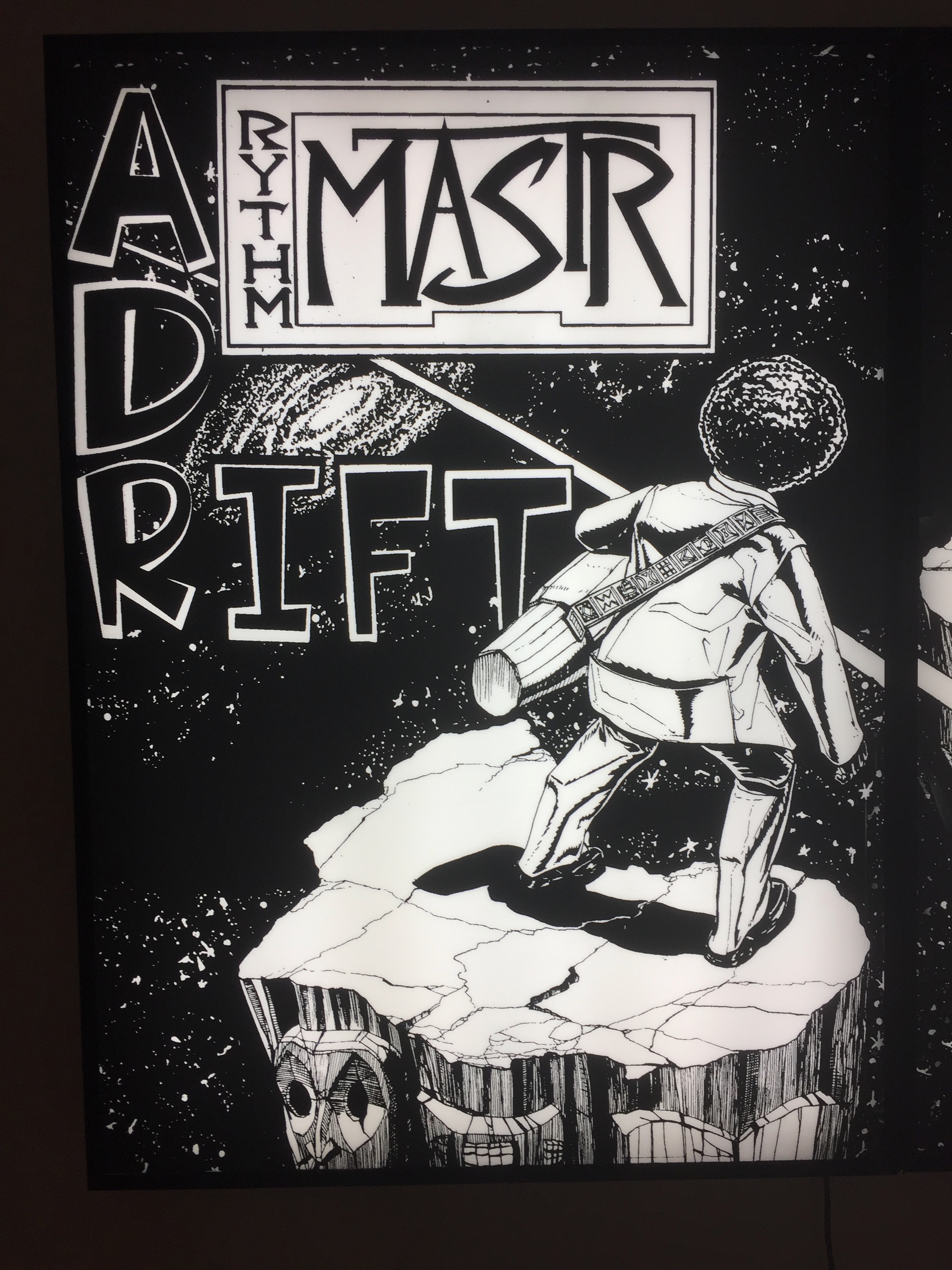

At the time the restaurant chain’s storefront sign featured a jester’s head popping out of a music box—the artist noticed the sign enveloped in smoke and illuminated by a hazy orange light– the Jack in the Box head was slowly rotating in the glow of the fires. This juxtaposition of the frivolity of the jester’s head looming high above the macabre chaos unfurling in the streets below it was not lost on the artist-it was an image that was seared in his memory. Marshall always wanted to find a way to paint this image, but never found a way to portray the outrageous irony that he associated with the scene that unfolded in front of him. After experiencing Mastry, Marshall’s triumphant 3 city retrospective now showing at MOCA, I see how those conflicting images inform the narratives contained in his work. Kerry James Marshall has chosen a layered artistic practice that represents a far more complex rendering of life that’s steeped in contradictions that challenge our understanding of the images that are placed in front of us and how we consume the messages contained within them. This is a juxtaposition that is interrogated at the core of Mastry and addresses a time when the artist first realized that black images weren’t hanging on the walls in museums. As much as Mastry breaks down those barriers and offers a glimpse of the complexities of black life that defy its narrow representation in popular culture, media and art, it also forces us to confront the systems that have constructed those physical and psychological barriers. The 80 works in the show reflect life, love, loss, visibility and identity while challenging us to consider the institutions that are complicit in sustaining the hyper-invisibility of the black body.

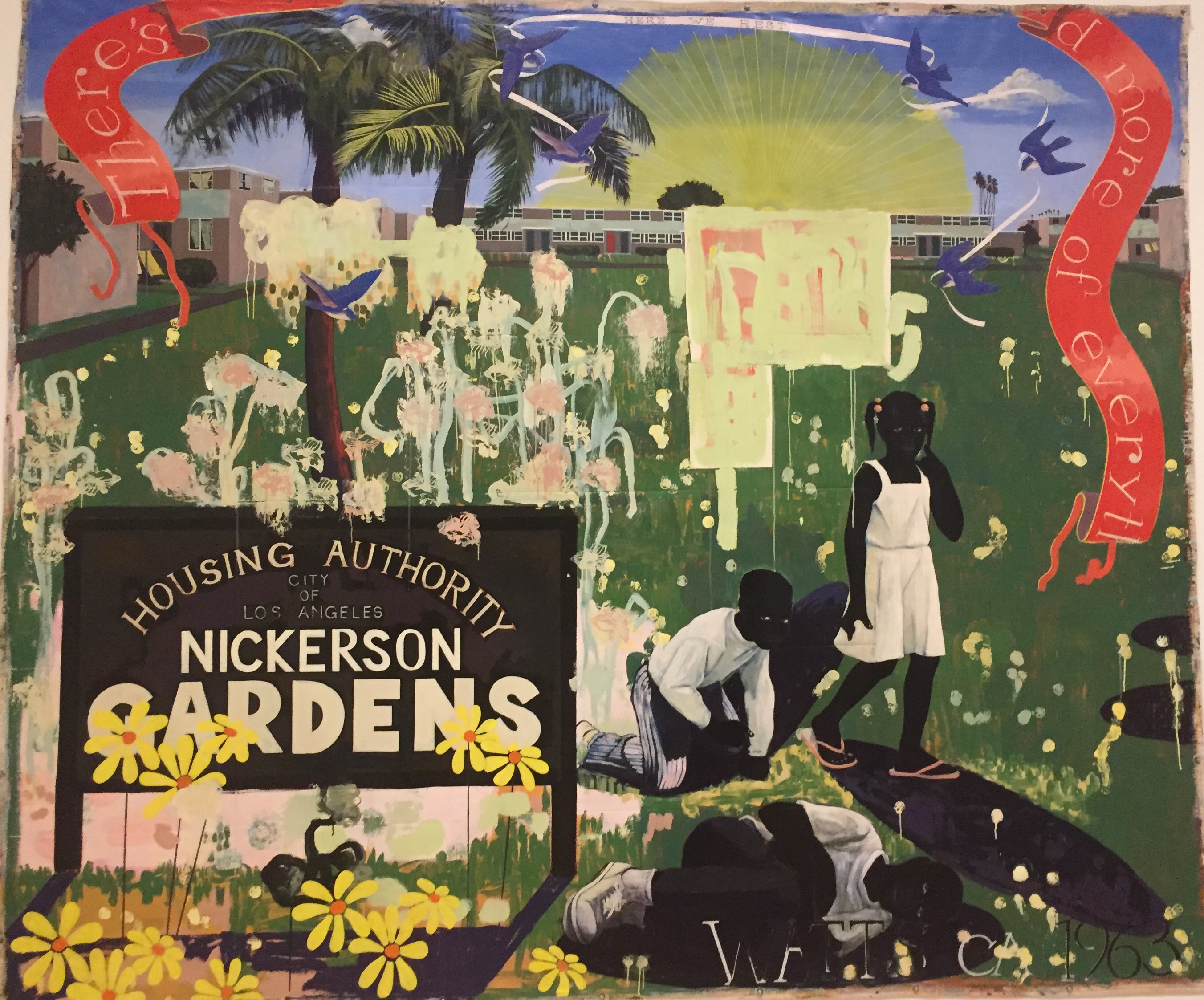

While Marshall never painted that depiction of the Jack in the Box, two works in Mastry touch on the disconnect between perception and reality. The first is from a series of 5 paintings from Marshall’s Garden Project series. Marshall’s “Watts, 1963” is a large mural on an unstretched canvas that features kids on a bright summer day playing in the grass wearing a sundress, shorts, and flip-flops. Behind them in the distance sits a row of low profile buildings with the radiating rays of a bright yellow sun rising behind the structures; flying bluebirds hover at the top of the canvas with ribbon banners in their beaks. Sitting prominently in the foreground of the painting is a sign freckled with bright sunflowers that reads, “Nickerson Gardens”. The scene is counter to everything we know about public housing in Los Angeles–this space between our perception contrasted with new information that challenges that perception is the space where Marshall likes to operate. According to Helen Molesworth, chief curator at MOCA Marshall’s paintings “are really good at containing information that’s contradictory” and in this work we see a fragmented juxtaposition between memory and current reality.

For Kerry James Marshall who moved to Los Angeles from Birmingham, Alabama in 1963 at the age of 8, the terror of institutionalized racism in a segregated Jim Crow south prompted Marshall’s family to join the second wave of the Great Migration to move west for better, more equitable opportunities. Within the same year that Marshall moved to Los Angeles, 4 girls were killed in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church. The Marshalls settled into public housing in Los Angeles and were some of the first residents of Nickerson Gardens, a public housing project that lauded an ethos of community building and quality of life. In Marshall’s Nickerson Gardens mural, we see an idyllic scene of a vibrant promise of orderly, neat, communal living punctuated by manicured lawns, palm trees, and well-attended resident gardens. The ribbon banner that’s held by the bluebirds is inscribed with the message “Here We Rest”; this is a proclamation that reaffirms that the new residents have been delivered from the harsh conditions of the south. However, in reality, the overt forms of discrimination and persecution manifested themselves in more covert, systematic forms within California in a slow boil of discriminatory housing practices, educational inequities, employment discrimination and police brutality that led to the Watts riots within two years. Decades later, the legacy of Nickerson Gardens became one of rampant crime, gang infestation, and poverty. In “Watts, 1963”, Marshall is not trying to paint a revisionist history of public housing, rather he is capturing a specific moment that remains overshadowed by its troublesome legacy. This forces the viewer to think beyond what they think they know about public housing as portrayed in the media, literature and popular culture. The compressed timeframe between 1963 and 1965 left an indelible mark on Marshall and on the other side of the gallery wall where “Watts, 1963” hangs is another work from Marshall’s Mementos and Souvenirs series that’s a nod to the Civil Rights movement and the events of Birmingham, Alabama.

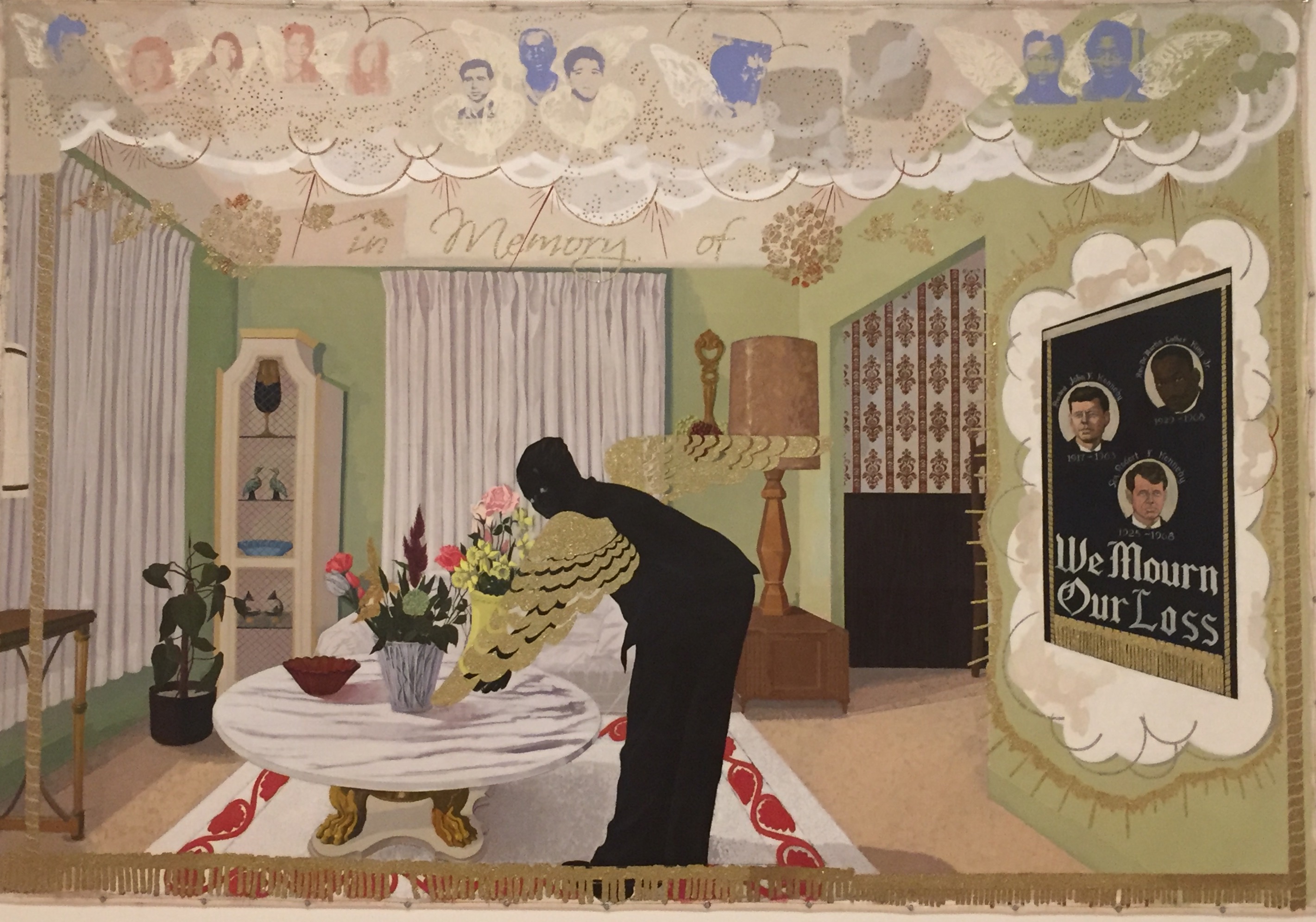

In “Souvenir 1”, another large unstretched canvas features a 1960’s style living room that feels like my grandmother’s Oakland house. In this painting, a woman with the gilded wings of an angel is carefully arranging items on a marble table. In a visual tableau that many black grandparents featured in their homes, portraits of MLK, JFK and Bobby Kennedy hang on a wall behind the woman. Looming above her appearing as thought clouds are the portraits of 11 slain civil rights icons including Malcolm X, Fred Hampton, Medgar Evers, Mississippi Civil Rights workers Cheney, Schwerner and Goodman along with Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson and Denise McNair who were the 4 little girls killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham. In gold cursive, the words “In Memory Of” are scripted below the portraits. As much as the work is in honor of the dead, it is also in reverence to the women who quietly led the civil rights movement and continue to be stewards of the movement’s legacy.

So much has been written about Marshall’s monumental 3 city retrospective (Mastry was previously shown at the MCA in Chicago and the Met), that I was reluctant to write about it. Of course it is a powerful show and Marshall cements himself into artistic canon with his work. There is no question of the importance of seeing black men, women and children on the gallery walls of our most revered contemporary art institutions. This is not just one work in a museum’s collection, or a group show featuring black artists, but Mastry was comprehensive, unapologetically black presentation. This is also a show filled with unexpected images that offer Marshall’s rendering of the past along with his vision of the future. There was a section of the show featuring hundreds of photographs, clippings, postcards and other pictures lying on the ground alongside ottomans and pillows that invite viewers to sit and pore over the pictures.

As an obsessive collector of images, Marshall is deliberate about how they are connected and presented. The artist famously loves to tell the story of when he was 5 years old and his Kindergarten teacher had a scrapbook of pictures containing old Valentine’s cards, magazine clippings, etc. He would love to thumb through the pages to ingest the images. Every day the teacher would give the best behaved child the book to read through during nap time. This kept Marshall motivated and behaved, but more importantly, his compulsion for collecting images and the connections these seemingly disparate visual messages is an obsession that has stayed with him.

He’s fixated on semiotics, symbolism, and signifiers which is apparent from the moment you are in a room with his work. Marshall’s large murals contain detailed images that reveal an infinite array of symbols, details, and messages that are at once familiar and yet completely new. When you want to learn more after you’ve seen a work of art you are onto something. This is what keeps me coming back to Marshall’s work and it’s a feeling that I chase whenever I experience art. In an Art 21 interview, Marshall explains how his practice is informed by Roland Barthes’ “semiotic challenge”, the practice of deciphering the hidden narratives in art, culture, music and how those hidden meanings may be obscured from us out of our desire to reflexively accept maxims based purely on their surface value. As he quotes both Ray Bradbury and Roland Barthes their influence is clear.

Marshall recounts an excerpt from Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 and says “‘Stuff your eyes with wonder . . . live each day as if you’d drop dead in ten seconds.’ And Barthes says, that in embarking on the semiotic challenge, the first moment in a semiotic challenge is the moment of amazement—that moment when you encounter a thing that is simply dazzling and fascinating to you, and that fascinating component compels you to want to know more about it. So, when I make work as an artist, I am essentially trying to make work that affects people that way… And so, what I try to do with my work is create that same sense of amazement, that same sense of wonder, that same sense of authority, that same kind of presence—so that things seem at once familiar and indecipherable, at the same time. And that familiarity and indecipherability can be called beauty.”

I originally saw Mastry back in March and concluded that I would need to see this show at least 3 times. I managed to see it twice, and both were equally powerful experiences. So all I can do here is encourage you to experience the show for yourself. This isn’t about making a case for Marshall. Nearly every written publication of this show has justified his place in the artistic canon. This is about sharing an experience it may be one that is not familiar to you, or it could be one that feels like home. Either way, you will walk out of his show with a better appreciation of beauty in all its forms.

Mastry at MOCA Los Angeles is in its final few days and closing on July 3. During this limited time admission to the museum is free.

Sources:

Leave a comment