winter 1998 issue

Kerry James Marshall by Calvin Reid

For Kerry James Marshall, 1997 was a good year: a MacArthur Fellowship, the Whitney Biennial and Documenta X. He spoke with Calvin Reid about the future of painting.

January 1, 1998

The past year has been a good one for Kerry James Marshall. His large sumptuous paintings were featured in both the Whitney Biennial and in Germany’s Documenta X; he has been awarded a MacArthur “Genius” grant to boot. Long before I ever saw his work, his name usually prompted admiring responses from artists who had. Marshall paints large, allegorical, allusive paintings invigorated by a complex conceptual weave of personal and social history, African American popular culture, African diasporan folk material, and a refreshing sense of awe and challenge in the face of Western painting’s daunting historical legacy. Born in 1955 in Birmingham, Alabama, Marshall grew up in LA. and made his reputation in Chicago; perhaps his work embodies something of the symbolic weight of those locations-the powerful social presence of the civil rights movement and their diffuse ethnic, social and urban legacies. In our telephone conversation Marshall pointed out the support he received from family and teachers (the late distinguished African American artist Charles White was both a professor and later a close friend), but he was quick to emphasize his own dogged, single-minded fascination with developing himself into a serious painter. His conversation is expansive—full of painterly analysis, but marked by a contagious delight in the daily prosaic labors of the studio, in art’s rarefied conceptual goals, and in the earned opportunity to bring the experiential lessons of his own life to the world of contemporary painting and art.

Calvin ReidYou grew up in Birmingham, Alabama. Was art a part of your life then? And what kind of influence did your family have on you as an artist?

Kerry James MarshallThat’s a complicated question to answer. In a lot of ways I was one of those fortunate people who consciously knew that being an artist was what I wanted to do with my life. I didn’t know at the time that it was called being “an artist!”

CR That’s fascinating that you recognized it so early.

KJMYeah, I’ve been single-minded since then. So when it comes to my family’s support, on one level it really didn’t matter. Not that they discouraged me, but my decision to go to art school was my decision. At the same time, it seemed like there were signposts all over the place saying, “Artists this way. . .” Everywhere I went I met the perfect person to get me to the next level.

CR For instance?

KJM Well, my family moved from Birmingham to California in 1963, and my teacher, Mrs. Foley, was in charge of all the holiday art decorations. She enlisted my aid, and I would stay after school and help her, and in between the turkeys and pumpkins she would show me technical things—how to paint flower petals, how to hold the brush. Stuff I really needed to know. And I used to watch this television program, John Nagy’s Learn to Draw, which was also highly influential in my development. Nagy was interested in more than just superficial forms of representation. He started with fundamentals, with the notion that everything you see is made up of three basic components: circles, squares and triangles; and once you learn to break things down and then put those shapes in perspective, you can draw anything. He showed me how to build forms, not just copy forms. Watching that program was the foundation for my search for the formal foundations of making art. And then there was Mrs. Clark, who was the head of the junior high school art department, she had competitions among the kids to see whose drawings got in the showcases.

CR So you’ve been showing since a very early age. (laughter)

KJM The irony was that there were lots of kids who were more talented than I was, in terms of copying things, like Marvel Comics’ images. . .

CR Sure, I certainly did that.

KJM Yeah, Marvel Comics was the godsend. My images tended to get overworked really fast, and had a lot of lines, erasures and scratches. I didn’t get a drawing into the case that often.

CR It’s interesting, you almost seem to be hinting toward some of the techniques that you use now in the floral patterns. Reworking and reworking…

KJM In a way. I latched on to process as an integral part of the overall appearance of the piece. Seeing that was just as important as having the piece look finished and slick. Maybe falling back on process was a way to compensate for my inability to be slick.

CR What was the Otis Art Institute in LA like?

KJM It was 1977 when I went to school full time, but I had been hanging around there from the time I was fourteen, taking summer classes in drawing and painting. I took a painting class with Sam Clayberger. And then a figure drawing class with Charles White in the evening after school.

CR What was it like taking a class with Charles White?

KJM I was fifteen and I was scared of him. He was somebody in a book, and for a kid, if you’re in a book. . .

CR You’re a godlike figure. . .

KJM Yeah. I had a little notepad, and I snuck into the room and hid way back in the corner, trying to be inconspicuous. He saw me and came over and said, “You can’t see anything from the back, get your chair and come up front!” So he took my stool and sat me in the front row and told me to draw. He talked to me, and showed me some demonstrations on how to draw heads, how to get the right proportions, and then he told me I could come back anytime I wanted to. That actually was the beginning of what became a long friendship.

CR It seems like you were embraced by the art fraternity at Otis.

KJM In a way. All of the adults invited me to be a part of what they were doing. One of the most amazing things about being at Otis, and hanging out in Charles White’s classes in particular, was in the evenings when they took their breaks, the lunch wagon would come and everybody would retire to the student lounge and have these round table discussions about philosophical and historical and political issues. I felt so out of place because I was so young. I couldn’t contribute to the conversation, but I wanted to more than anything. I thought, “If I want to be an artist too, I’ve got to be able to do that. I’ve got to know something!”

Kerry James Marshall, Our Town, 1995, acrylic and collage on canvas, 100 × 144 inches.

CR Do you feel that you reached a serious level of art-making, beyond apprenticeship, while you were at Otis?

KJM In a way I had reached it before I got there. I had an unwavering desire to be like a lot of these artists I admired from art history books. In fifth grade I wanted to paint paintings like Goya’s black paintings. My whole developmental period was geared toward trying to know what they knew, whatever it was that made their work look the way it looked. I was struggling with simply trying to master the materials and the methodologies of making work. Periodically I tried to say something with the work I was doing, but I knew I wasn’t equipped to use the medium or use the tools the way they could be used effectively. So I didn’t worry too much about being self-expressive. That will come later, I figured. It takes half a lifetime, really, to develop to a point where you can start to speak effectively with whatever the tools are you’re trying to master. I don’t think that started happening to me until about six years ago. Then I felt I had sufficiently mastered the forms and the materials of art-making, and the ideas that govern it, to be able to say something with it that was worthwhile.

CR And to be able to bring in, I assume, what you think about the world and what you’d found out about the world.

KJM Right. It takes time to internalize the things that you’ve experienced. Before then, you can only deal with surface issues. Until you’ve internalized certain experiences, you don’t have access to how complex those things are. You can’t filter them through your personality the way you need to to make the work speak in your own voice.

CR What was your work like at the time of the Studio Museum residency?

KJM When I graduated from Otis in ‘78, I was doing collages exclusively with found materials. I didn’t start drawing and painting again until 1980.

CR What were the collages like, were they figurative works?

KJM At first. They started out as small, cut paper collages reminiscent of Bearden’s collages, but a little more austere, not so syncopated as Bearden’s. Not so many fragments of figures and things.

CR Austere in terms of color as well?

KJM Yeah, they’re dominated by blacks. So there’s a sharp contrast between the images and their ground. The ground was almost always flat black, and then I would put my narrative imagery on top of that ground. They were more figurative at first, but then they turned abstract.

CR No narrative imagery at all?

KJM None. In 1980 I started painting again. After doing those abstract works the first figurative painting I did was called A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self. A small, egg tempera painting. It was the first time I used what eventually became these black figures that I’m currently using. So from 1980 until ’84, when I applied to the Studio Museum, I was developing that.

CR What was the Studio Museum like?

KJM It was great. I had wanted to go to New York to live—I had this idea that you had to go to New York at some point. Allison Saar had done the residency at the Studio Museum, and she encouraged me to apply. There were a lot of people from the Brockman Gallery scene who had left LA and gone to New York—the Brockman Gallery was one of the first black-owned galleries in LA. But coming to New York, being at the Studio Museum, was an introduction to the black New York arts scene. And New York was great for me. I felt welcome all the time.

CR It’s interesting, because there are also people who feel they have to be in New York, but they don’t really have a good experience here for one reason or another.

KJM Maybe the difference is that I didn’t go to New York to show work. I went to New York just to be in New York. I’ve never been that anxious to show work. I’m always focused on making it. I know a lot of people who took their work around and beat the pavement and had horrible experiences. But I didn’t want anything from anybody.

CR You just wanted to work.

KJM I was going to work, nobody could stop me from doing that. And what I was interested in, nobody else could help me with. Development is your own responsibility. I show when opportunities are offered to me, but I don’t go out looking for shows. Because in the end the only thing I can do anything about is how well I’m doing my work: If I do it to my satisfaction, then everything else is what it is.

CR What was it like moving to Chicago?

KJM It was rough at first because I didn’t know anybody except my future wife and her family. And, I came in the dead of winter.

CR Did you have a studio?

KJM No, I had a six-by-nine room at the “Y.” I started working there, making small paintings and prints. It was while I was at the “Y” that I first started collaging sheets of paper onto canvas to make a grid, and then I started painting on those. Those first ones were Harlequin Romance novel covers.

CR When were you able to move into doing larger things?

KJM We got married in ‘89 and moved into an apartment in Hyde Park, and there I started painting again on a larger scale. I used those paintings to apply for an NEA grant, and through that grant I got a studio, the same space that I’m in now. That’s when the paintings got really big.

CR Let me ask you about the paintings. One of the things I find really fascinating about your work is the tension between your figuration, the symbolism, and the flat painting field. You juggle the two. Could you talk a little about that?

KJM I see these latest paintings as a synthesis of all the things that I have been studying over the years. Each of those aspects you were just describing, I had been doing in very isolated, discreet forms. There was a period when I was doing flat, decorative paintings; a period when I was doing classical drawings; abstract paintings; monoprints and woodblock prints; and then there was a period when I did a lot of collage. The paintings now are an exact synthesis of all of those things happening simultaneously in one visual field. I’ve always been interested in the formal issues of works, from medieval paintings all the way to de Kooning and Warhol. Once you have mastered the language of art-making, then you have to try to find ways to speak eloquently with it, and do so with complete control of how much tension you are putting on the spring. You should be able to tweak it, even a millimeter, to get it fine-tuned, and you can’t do that unless you are completely conscious of the devices you’re using all the time. I finally got to the point where I understood why medieval painting looked the way it looked; why Giotto’s paintings worked the way they worked; why Michelangelo’s painting’s appealed to me, de Kooning, Pollock, and Warhol. . . Then I could employ the devices they used to support meaning in my work.

CR I’m also interested in how you use what I would describe as symbolic perspective. You bring in a volumetric space, but then there’s that flat painting space. There’s a great tension there.

KJM These paintings are loaded with contradictions. That’s what makes work exciting. Taking it to the edge, where it’s so full of contradictions that in some way there’s no reason why these works should hold together formally, but somehow they do.

CR That’s the magic of art.

KJM That is. I’m one of those people who still believe in the idea of mastery. And I don’t care if it’s video, or painting, or drawing. What really matters most is how masterfully you manipulate processes. Painting has been the stepchild of art for a while now, largely because of the mastery question.

CR Some people would say to some extent it still is.

KJM Yeah, but I would say that many of the people who say that couldn’t make engaging paintings if they wanted to. It’s not the form that’s the problem, it’s the users of the form. There are so few people who have the level of mastery that’s required to make compelling work in any medium, let alone painting, which takes a long time to learn how to do well. The issue for me has never been whether it’s possible to paint, but how to find a way to make painting exist powerfully in the face of all of the other options artists have available to them. And to understand if it can, not because somebody said so, but because you’ve tested the possibilities.

CR As a painter you have this extraordinary history looming over you.

KJM Right, which is so magnificent. In the face of that it’s hard to do anything. But if you’re making art, you want to be tested against the best. You don’t want to succumb to the authority of previous masters, but you want to see if you can find a place to get up next to them. For me, it’s more interesting and more exciting to do that than to simply admit that some area is exhausted, because that admission to me simply says that you lack the imagination or capacity to find some area of value in that form.

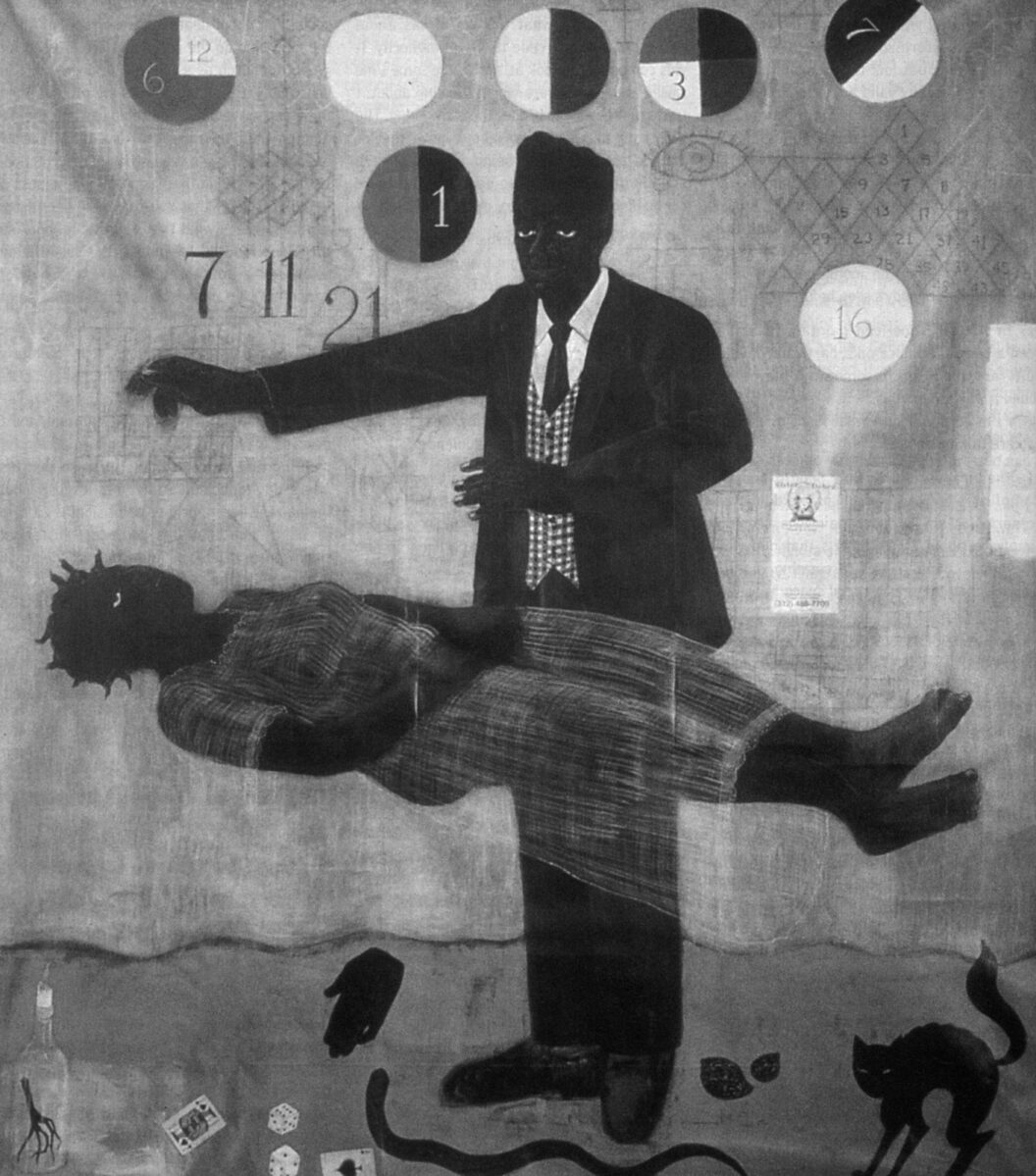

Kerry James Marshall, When Frustration Threatens Desire, 1990, acrylic and collage on canvas, 80 × 72 inches.

CR One painting I’m really interested in of yours is When Frustration Threatens Desire. Can you talk about how you begin a painting and use that one as an example?

KJM The title of that painting is a quote from Paul Garon’s book, Blues and the Poetic Spirit: "Magic is evoked when frustration threatens desire." It’s talking about the moments when voodoo and things like that are employed as devices to win over somebody, somebody that you usually want but can’t get. And a lot of blues songs are built around…

CR What you can’t get.

KJM Yeah. I had a friend in LA who taught folklore and theater at UCLA. They did a folk-life festival for South Central, LA, and I helped with some of the research. We went around to see a lot of things, one of which was the Bombay Candle Company on Central Avenue. I had passed that place all the time going to and from school and never thought about what was going on in there. Until I was doing this research and found out that people would go there to get their candles dressed and to get spiritual readings. There was Santería going on in my neighborhood for decades, and I didn’t even know it. All of these people were going in to find a solution to the frustration of their desire. They needed that “Lover-Come-Back-To-Me” spray or the "Money-In-Your- Palm" grease. And there were not just a few people going there, there were lots of people. So that painting came out of knowing about the Bombay Candle Company. And also partly out of my love for country blues music, the really rural delta blues. If you take all of those things and put them together, you end up with a painting like When Frustration Threatens Desire.

CR I’m fascinated by its symbolic elements. There are certain things I intuitively recognize as folk, country, and voodoo symbolism, and there are other things, the circular forms, that I don’t know about. The composition is magical, comical, and kind of eerie.

KJM Look at how complex the African American cultural experience is in the United States, there are all of these ways in which black people synthesize Western traditions with African traditions. So in that painting, those circular shapes are symbolic representations of the seven African powers from the Yoruba pantheon. Those circles are divided into that particular guise as color, and that number on those circles is their magic number. But then you also have these cabalistic symbols floating around, and some ve-ve from Haitian Voodun. All of that is mixed into a Western magical tradition, like the woman floating, sawing her in half, stuff like that. The question is, what part of this is hocus-pocus, and what part is really powerful? What also started to crystallize in that painting was a way to bring together not only Western traditions of pictorial representation, but folk traditions of painting that have an equally valid authority. I don’t see much difference between using Giotto or Bill Trayler as a point of reference. To me they’re the same. Their work has a certain power. The same thing with somebody like Sam Doyle. Why can’t Sam Doyle be brought into the mix? Who says Brancusi is more powerful than Sam Doyle? I don’t. It’s all up for grabs, it’s all material that can be combined to make something that nobody’s seen before.

CR In African American painting there has been a certain reliance on a particular kind of cultural symbolism. In some ways maybe you found a way around this.

KJM I’m not quite sure what kinds of symbols you are talking about.

CR The images of the Cub Scouts and the Campfire Girls, very ordinary middle-class scenarios. Many of your paintings seem to simply be about love-there’s that depiction of a black couple in this fascinating room, a painting that captures a social space as well as a psychological space.

KJM Black people occupy a space, even mundane spaces, in the most fascinating ways. Style is such an integral part of what black people do that just walking is not a simple thing. You’ve got to walk with style. You’ve got to talk with a certain rhythm; you’ve got to do things with some flair. And so in the paintings I try to enact that same tendency toward the theatrical that seems to be so integral a part of the black cultural body. When you talk about this obligation to articulate some socially relevant issue, a lot of that has everything to do with where I came from. You can’t be born in Birmingham, Alabama in 1955 and not feel like you’ve got some kind of social responsibility. You can’t move to Watts in ’63, and grow up in South Central near the Black Panthers headquarters and see the kinds of things that I saw in my developmental years, and not speak about it. That determined a lot of where my work was going to go.

But also, I came into contact with Charles White at the Otis Institute, and his work always seemed to be about something. It was never about him, it was always about something larger than he was. It had something to do with the black cultural body as a whole. And so from him I also got this feeling that your work had to mean something to people. I really was turned on by Goya’s paintings; just looking at that work affected me. And then seeing Käthe Kollwitz’s work—what the work was about socially didn’t supercede its visual authority. It was compelling to look at, and at the same time raised issues that were worth thinking about. I try to make work that does the same thing. The paintings are as much about how they’re painted as about what’s being painted. They’re equally important, and so each one has to be compelling enough to carry interest by itself.

CR That seems to be an organic thing for you: how they’re made, and what they may be saying.

KJM I actually don’t think art is very important. In some ways I don’t think artists should be given the benefit of the doubt under any circumstance. You still have to earn your audience’s attention every time you make something. Whenever I come into the studio I’m struggling first to clarify my idea, and then win the attention of multiple audiences.

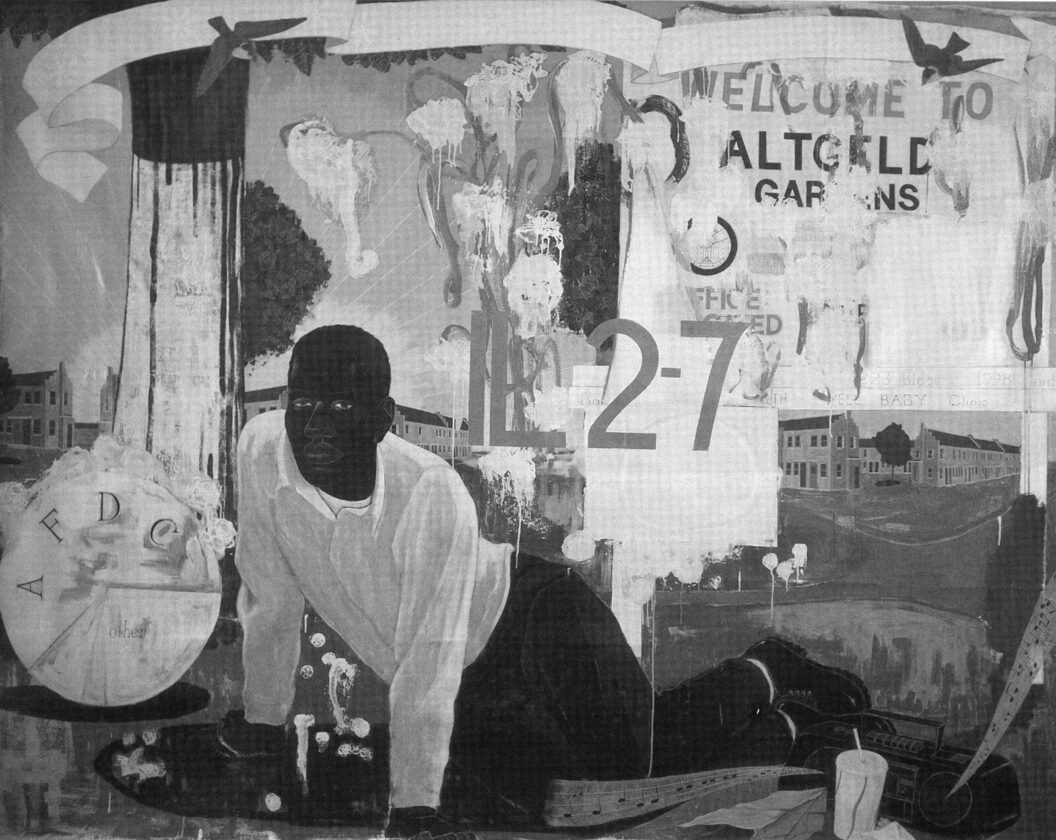

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Altgeld Gardens), 1995, acrylic and collage on unstretched canvas, 78 × 103 inches.

CR Some of the things I’ve read about your work talk about the irony in the Projects Paintings. I’m curious to hear you discuss those paintings, because you in fact lived in the projects in Watts. . .

KJM Yeah, Nickerson Gardens.

CR At that time, they were very different from the vision we have of projects today. That had to be a part of these paintings too, both the irony and perhaps some sense of personal memoir?

KJM Yeah, what I wanted to show in those paintings is that whatever you think about the projects, they’re that and more. If you think they’re full of hopelessness and despair, you’re wrong. There are actually a lot of opportunities to experience pleasure in the projects. There are people whose idealism hasn’t been completely eradicated just because they’re in the projects. A lot of people who live in the projects have a Disney-esque view of the world, in spite of everything else that’s going on there. I wanted to try and communicate in those paintings how much more complex those projects and the people who live there actually are.

That painting, Many Mansions, tries to say something about death and resurrection. All of the guys who do the gardening are dressed for going to church or a funeral. And the plots in which they’re planting flowers are proportioned to be like grave plots. You could say that they’re digging their own graves. Also, those Easter baskets—Easter is a celebration of resurrection. If there’s anything that suggests hopefulness it is the possibility that you can come back from anything. That’s what that suggests to me. And the bluebirds and happiness, the sun shining so bright—all of those things are a fantasy of happiness. A fantasy of happiness that’s not necessarily an impossibility.

CR These paintings all have rich, painterly effects in them. Is that something that you need to add, rich, almost abstract markings?

KJM In the end, I’m making a painting, and I don’t care what it’s about, it’s got to be a good painting first. A lot of that stuff is so that it’s interesting to look at. Sometimes it’s just about the paint, where a drip of paint signifies a drip of paint, and that has some art historical significance. It lets you know that I understand exactly what the language of the paint is, and how to use it when it’s appropriate. But it also gives me a chance to disrupt the narrative flow, so that it doesn’t present these things in a seamless, holistic way, but a vision that has complex overlays that somehow seem unrelated, but have everything to do with the way you ought to read this situation.

CR Let me skip to a couple of things that I want to get your comments on. Obviously, I have to ask you about the ‘95 Biennial. What was the effect, or non-effect of that oft-discussed encounter with Klaus Kertess in the New York Times? I know you’ve probably had to answer this question many more times than you ever wanted.

KJM Maybe we’ll put it to rest. For me, it wasn’t really that big a deal. The truth is certainly more complicated than what was described, the impression that piece ended up creating was: Here’s this black man who is an outsider, struggling to get in and become part of the mainstream. They did everything they could to paint that picture of me, including choosing the one photograph out of eight rolls of film that placed me outside the studio in what looked like an alley. When Klaus Kertess came to see me, I was working on paintings for the “About Place” show at the Art Institute. And I was committed to a show at the High Museum and a show in Berlin. I was actually quite busy. He said to me, “I would like for you to be in the Biennial.” I said, “Thank you. I would like to be in it, but how much work would you want? Because I have all of these other things that I’m committed to?” He said two paintings, and I said, “I’ll start two more paintings, and then I’ll send you Polaroids of them and you can tell me whether they work for you or not.” So I took that as a challenge, to see what the limit of my capacity to produce good work was.

CR And they took that Polaroid, that was framed in the Times story. . .

KJM Yeah, it was like I just started sending the Whitney Polaroids. But we had agreed I’d send them from the start so that Kertess could get some sense of what I might be thinking about trying to do for the Biennial. We had a little bit of correspondence for a while, and at a certain point it started to look like I wasn’t going to be able to do it and I told him that in a letter. After that letter, I never heard from him again. The crazy irony is that I could have sold one of those paintings I started for the Whitney to the Whitney after the last Biennial.

CR Well, you know. . . (laughter) Maybe your way is the best way, you just do the work and it comes around in the end…

KJM In the end all I could do was do the work.

CR But your experience in this Biennial?

KJM I was pretty pleased with the response. I had been committed for a long time to proving that there was still some possibility for painting to exist in a contemporary context and hold its own, maybe more than hold its own. Being in that Biennial, being in Documenta, getting the Herb Alpert award, and then the MacArthur grant, that says that there is still something left to be done with an archaic medium like painting. I know there are a lot of people who paint who were heartened by my success. There are no authorities out there who can determine what’s valid and what’s not valid. And if anything, the course to take is certainly not the popular course at any moment in history. If art is supposed to be about anything, it’s supposed to be about an independent spirit and creative possibilities. And if you’re focused on that, then you’ll be fine.