How Important Is Lead Poisoning to Becoming a Legendary Artist?

For masters who used lead paints, such as Michelangelo and Goya, art was literally pain.

In 1713, Italian physician Bernardinus Ramazzini described in his De Morbis Artificum Diatriba a mysterious set of symptoms he was noticing among artists:

“Of the many painters I have known, almost all I found unhealthy … If we search for the cause of the cachectic and colorless appearance of the painters, as well as the melancholy feelings that they are so often victims of, we should look no further than the harmful nature of the pigments…”

He was one of the first to make the connection between paint and artists' health, but it would take centuries for painters to switch to less-harmful materials, even as medicine gradually clued into the bodily havoc “saturnism” could wreak.

The 1834 London Medical and Surgical Journal describes sharp stomach pains occurring in patients with no other evidence of intestinal disease, thus leading the authors to suspect that this “painter’s colic” was a “nervous affection” of the intestines that occurs when lead “is absorbed into the system.”

Paints weren’t the only source of lead overdose in past centuries, though. Through the 1500s, lead was a common sweetener in wine, in the form of “litharge,” causing periodic outbreaks of intestinal distress throughout Europe. Occasionally, lead was even used as a medicine; the 11th-century Persian physician Avicenna’s Canon mentioned its usefulness in treating diarrhea. In the Middle Ages, lead could be found in makeup, chastity belts, and spermicides.

Though typesetters, tinkers, and drinkers of lead-poisoned wine fell victim to saturnism, the disease was perhaps most widespread among those who worked with paint.

The symptoms of this “colic” ranged, but they often included a “cadaverous-looking” pallor, tooth loss, fatigue, painful stomach aches, partial paralysis, and gout, a buildup of uric acid that causes arthritis—all of which resemble the symptoms of chronic lead poisoning seen today. In fact, the ailments that many renowned artists experienced didn't just prompt their gloomy works—they might have been caused by them, too.

Lead poisoning among historical figures is famously difficult to prove, in part because the condition was not known or recognized in most of their lifetimes. We can’t know whether the delusions, depression, and gout many Renaissance masters experienced can be attributed to their paint or just their physiologies.

Julio Montes-Santiago, and internist in Vigo, Spain, recently evaluated the existing evidence of lead poisoning among artists across five centuries for a new paper in Progress in Brain Research. Based on the available descriptions of their materials and symptoms, history’s most famous sufferers of lead poisoning, he argues, likely included Michelangelo Buonarroti, Francisco Goya, Candido Portinari, and possibly Vincent Van Gogh.

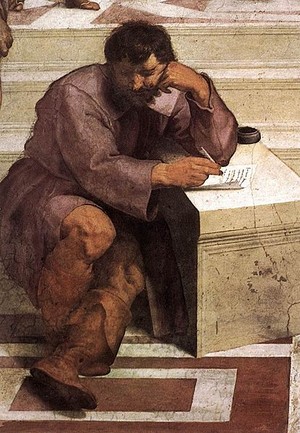

(Wikimedia Commons)

Michelangelo, for example, was painted into Raphael's fresco, The School of Athens, with a deformed, likely arthritic knee, according to the author. That, combined with letters from Michelangelo in which he complains of passing stones in his urine, suggests to Montes-Santiago that he might have suffered from paint- and wine-induced gout.

Many art historians think Van Gogh might have suffered from epilepsy and bipolar disorder, but Montes-Santiago argues that lead poisoning likely contributed to his delusions and hallucinations. The artist was known to have sucked on his brushes, possibly because lead has a sweet aftertaste. Meanwhile, other scholars have disputed the lead poisoning hypothesis, arguing that the root of Van Gogh’s distress was porphyria, malnutrition, and absinthe abuse.

Goya occasionally applied his paints directly to the canvas with his fingers, which Montes-Santiago argues is one reason he experienced problems like constipation, trembling hands, weakness of the limbs, blindness, vertigo, and tinnitus. In his famous 1820 self-portrait, Goya painted himself being embraced by his doctor.

Musicians Beethoven and Handel also might have been afflicted with saturnism, but not because of the nature of their craft. Samples of Beethoven’s hair examined by the Pfeiffer Research Center in Illinois showed high lead concentrations, possibly as a result of the “high content of lead in the Hungarian wines that the musician drank, the repeated biting of his lead pencils, and lead-rich medicines prescribed by his doctor,” Montes-Santiago notes.

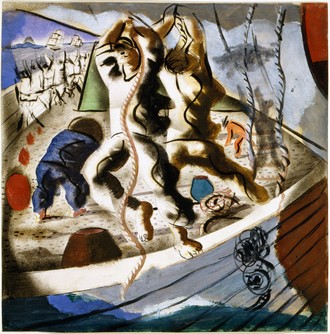

The best evidence for lead poisoning, though, exists for Candido Portinari, the 20th-century Brazilian painter of massive, neorealist murals. Portinari used paints that were similar to those used by Van Gogh and was diagnosed with saturnism after digestive hemorrhages prompted a hospitalization in 1954.

He was advised by doctors to switch materials, and he tried, but he ultimately returned to his old paints. He died at age 58 in 1962 after a bout of severe digestive bleeding.

Though some of the earlier artists may not have known about the connection between their materials and their health, Portinari certainly must have.

By the mid-1800s, the health impacts of lead had become clear. An 1836 book notes, for example, “The business of a Painter or Varnisher is generally, and not without reason, considered an unhealthy one. Many of the substances which he is necessarily in the habit of employing are of a nature to do injury both to the nerves and the inside.”

According to Montes-Santiago, though, Portinari seemed to strongly prefer working with the lead paints, reportedly saying “They forbid me to live,” about the doctors who urged him to give them up.

“Sometimes, art hurts,” Montes-Santiago writes. “But it also can save.”