Fed raises rates, keeps forecast for 3 hikes in 2018

Paul Davidson

Paul Davidson

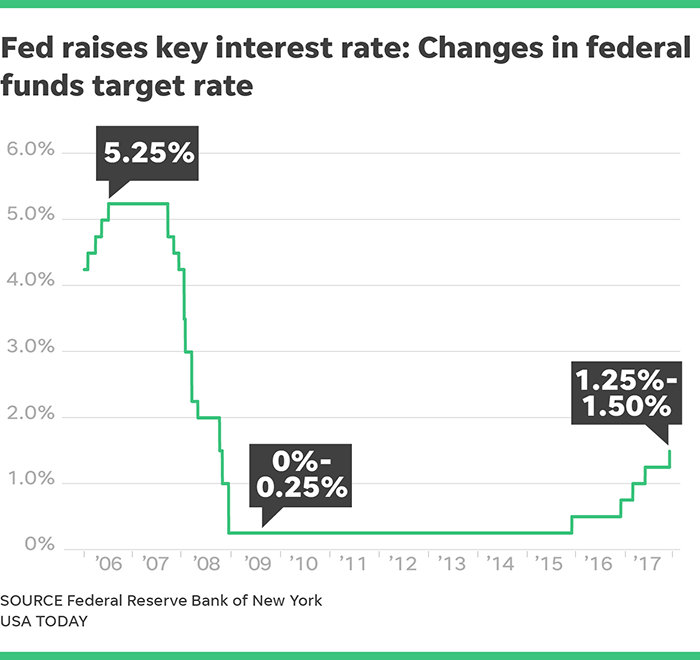

WASHINGTON — With a notable upgrade to its economic outlook for 2018, the Federal Reserve agreed to raise its key interest rate Wednesday and maintained its forecast for three hikes next year despite sluggish inflation.

As widely expected, the Fed’s policymaking committee lifted its benchmark short-term rate by a quarter percentage point to a range of 1.25% to 1.5%. It marked the central bank’s third such rate increase this year and a vote of confidence in an economy that has perked up in recent months. Still, it was just the fifth hike since the recovery from the Great Recession began in 2009.

More:How the Fed interest rate hike could affect your wallet

More:Will a Fed interest rate hike mean more interest in your savings account?

Learn more: Best mortgage lenders

More:How a Fed rate hike could impact your auto loan

The move is expected to ripple across the economy, nudging up rates, most noticeably for credit cards, adjustable-rate mortgages and home-equity lines of credit. The effect on fixed-rate mortgages is likely to be less pronounced.

The Fed marginally pushed up its economic growth forecast for 2017 to 2.5%, but sharply raised it for 2018 — to 2.5% from its 2.1% estimate in September, in an apparent nod to the Republican tax-cut stimulus.

Policymakers also increased their growth estimate to 2.1% in 2019 and 2% in 2020, up from 2% and 1.8% respectively. They now expect the 4.1% unemployment rate to fall to 3.9% by the end of next year, below their prior forecast.

"We see changes in tax policy as supportive of a modestly stronger economic outlook," Fed Chair Janet Yellen said at her final news conference.

She added: "At the moment, the U.S. economy is performing well. The growth that we're seeing is not on the back of ... an unsustainable run-up in debt (as occurred during the housing bubble). There's much less to lose sleep over than there has been in quite some time."

The Fed is also shrinking the $4.5 trillion portfolio of assets it amassed after the financial crisis, an initiative that could push long-term rates slightly higher.

The Fed's two-day meeting took place against a backdrop of imminent changes in its leadership. Yellen, a Democrat, is expected to step down in February when chairman nominee Jerome Powell takes the helm.

Powell, a Fed governor and Republican, is likely to continue the cautious interest-rate policy advocated by Yellen. On Wednesday, the Fed left its forecast for the federal funds rate intact, projecting three quarter-point increases in 2018 and two in 2019, based on policymakers’ median estimate. The Fed also left unchanged its estimate that the rate will be 2.7% at the end of 2019 and 2.8% over the longer run. However, it bumped up its estimate of the rate at the end of 2020 to 3.1% from 2.9%.

Fed officials maintained their forecast for core inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy items, at 1.5% this year, 1.9% in 2018 and 2% in 2019.

In a post-meeting statement, the Fed noted that inflation has been running below its 2% target. But it reiterated that it expects it to drift toward that level “over the medium term.” It added that “the labor market has continued to strengthen” and “economic activity has been rising at a solid rate.” The Fed said hurricane related disruptions and rebuilding will continue to affect the economy in the near-term but are unlikely to alter the economy’s course.

Yet with inflation still scant, Chicago Fed President Charles Evans and Minnesota Fed chief Neel Kashkari dissented from Wednesday’s decision to raise rates.

Ian Shepherdson, chief economist of Pantheon Macroeconomics, believes unemployment will fall faster than the Fed projects, sparking sharper inflation and more rate hikes. "The Fed forecasts an endless expansion, with minimal inflation pressure," he wrote to clients, a view he called "hopelessly unrealistic."

Fed policymakers are struggling to respond to conflicting economic signals. On the one hand, growth picked up to a better than 3% annual pace in the second and third quarters, its best six-month stretch in three years. The 4.1% unemployment rate marks a 17-year low. And the economy has added an average 174,000 jobs a month so far this year, a sturdy total considering that low unemployment is making it harder for employers to find workers.

The Republican tax-cut plan, which Congress is expected to pass, is projected to further juice the economy. That could trigger faster wage and price increases, forcing the Fed to hike rates more rapidly to offset the tax stimulus and keep inflation in check.

Yellen said any rise in economic growth spurred by the tax cuts would be "very welcome," as long as they're consistent with the Fed's employment and inflation objectives. But she added that she worries about their effect on the deficit. "Taking a significant problem and making it worse is a concern to me," she said.

At the same time, inflation so far has remained surprisingly weak. The Fed’s preferred measure of core inflation was at 1.4% in October, well below the Fed’s annual 2% target. And the Labor Department said earlier Wednesday that a different reading of core inflation ticked down in November.

Some Fed officials have chalked up meager inflation to temporary factors and expect it to pick up as employers boost pay more rapidly amid intensifying struggles to find workers. Others say inflation is suppressed by longer-term forces, such as discounted online shopping and feeble gains in productivity, or output per worker, that are constraining paychecks.

That leaves Fed policymakers with a dilemma: Continue to raise rates gradually to avoid disrupting the recovery or quicken the pace to be better positioned for an eventual spike in inflation. So far, the Fed has stuck to the gradual approach.

Besides Powell’s ascendance to the chairman role in February, President Trump also must fill what will soon be four vacancies on the Fed’s seven-member board of governors. The policymaking committee is made up of those governors as well as 17 regional Fed bank presidents.