Jarvis Kennedy watched two stories unfold on the news on Thursday night: the surprise acquittal in Oregon of seven members of the armed militia that occupied the Malheur wildlife refuge and the mass arrest of Native American activists protesting the Dakota Access oil pipeline.

“Those guys are unarmed,” said Kennedy of the Native American protesters in North Dakota, “but these cowboys who came in with guns – they got off.”

Kennedy, the sergeant-at-arms of the Paiute Indian tribal council in Burns, Oregon, was a vocal opponent of the militia’s 41-day occupation of land that includes Paiute burial grounds.

“I was in shock and disbelief, mad, and pissed off,” Kennedy said of his reaction to the verdict.

Kennedy was not alone in his dismay at the acquittal of Ammon and Ryan Bundy and five other defendants. The news stunned many across the country, leaving them to wonder how the government failed to convict members of an armed militia that brazenly occupied federal property and then broadcast it live on social media.

“I had to pull over, I was so shocked,” said S Amanda Marshall, a former US attorney in Oregon who is now in private practice. “I had already decided that the case was over. I thought I heard it wrong.”

“I thought this would be a slam dunk for the government,” said Tung Yin, a professor at Lewis & Clark Law School in Portland, Oregon, who watched the case closely. “When the occupation was winding down, I assumed [the defendants] would all plead guilty because I didn’t see any defense.”

One of the jurors told the Oregonian that the government had failed to prove a key part of the conspiracy charge – that the defendants had the “intent” to keep federal employees from doing their jobs.

“It should be known that all 12 jurors felt that this verdict was a statement regarding the various failures of the prosecution to prove ‘conspiracy’ in the count itself – and not any form of affirmation of the defense’s various beliefs, actions or aspirations,” Juror 4 wrote in an email to the Oregonian.

“That is always the hardest thing to prove in any criminal case,” Marshall said. “You almost never have direct evidence of intent. As prosecutors, we always struggle with how we’re going to be able to explain intent to the jury.”

Angie Bundy, Ryan’s wife, who sat through many of the court proceedings, said she thought the prosecution’s case was undermined by the fact that the US government had relied heavily on more than a dozen paid informants who were present at the refuge.

Defense lawyers had repeatedly raised concerns about how those confidential informants may have influenced the actions of the defendants during the protest.

“That really backfired on them,” Angie said.

The mother of eight also argued that the government had failed to make a case that her husband and their supporters had any “intent” to impede the government.

Robert Salisbury, defense attorney for defendant Jeff Banta, who was one of the final holdouts at the refuge, said that the government might have been more successful if prosecutors had filed “criminal trespassing” charges in state court.

He noted that police officials essentially allowed the occupation to go on for weeks, during which time law enforcement stayed away and failed to order the activists to leave in any formal manner.

Ammon’s lawyers, for example, noted in court that he was able to leave the refuge and eat at a local Chinese food restaurant without facing law enforcement or arrest. The fact that he and others could move freely in and out of the occupation suggests that the government was not forcibly blocked from carrying out its duties at the refuge, the defense argued.

“The government was very arrogant in the way they brought this whole case,” Salisbury said. “The jurors picked up on that.”

That analysis was backed up by Juror 4’s email to the Oregonian, in which he wrote: “The air of triumphalism that the prosecution brought was not lost on any of us, nor was it warranted given their burden of proof.”

Salisbury also noted that the firearm charges were dependent on the conspiracy claims, meaning once the government failed to prove there was a coordinated effort to block federal workers, it no longer mattered whether the defendants had brought guns to the refuge.

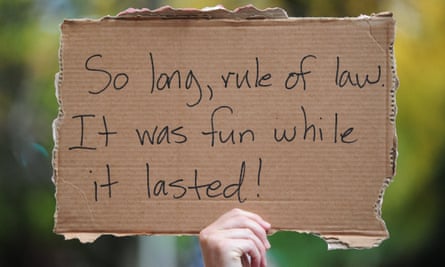

The acquittal has raised concerns that it will encourage other militias to take action against the federal government.

Ryan Lenz, editor of the Hatewatch blog for the Southern Poverty Law Center, who has closely studied the Bundys and rightwing militias, said the decision could have dangerous ramifications.

“It’s a disaster. It emboldens the anti-government movement that grew as a result of the Bundys’ actions.”

Lenz argued that the accusation that the Bundys were conspiring to impede government workers may have missed the mark.

“That wasn’t what they intended to do,” he said. “It was not about preventing anybody from going to work. It was essentially about altering the law of the land through threats, intimidation and force.”

But Yin said that he thought the prosecutors’ decisions were reasonable.

“Conspiracy is actually a favorite tool of prosecutors because usually it is fairly easy to prove,” he said. “I don’t think they made a mistake in charging it.”

Still, Yin added, the outcome should serve as a warning to prosecutors preparing for the upcoming trial over the Bundy family’s 2014 armed standoff with the government over grazing fees.

“It’s something I would be concerned about if I was the US attorney in Nevada,” he said.

Peter Walker, a professor of geography at the University of Oregon, was outraged by the verdict – and by the charges prosecutors had chosen to pursue.

“The community suffered horribly as a consequence of the militia presence,” Walker said. “The conspiracy charge captured one small part of what happened in Harney County, and the community was frustrated by that in first place. Then, to have lost on those narrow charges basically means that there was zero accountability on the occupiers for the suffering that they caused.”

Kennedy said the verdict was typical: “We as native people, we don’t know what justice is. We never had it before. We hope for the best and expect the worst, and this time we got the worst.”