Professional athletes are shooting stars: they burn bright as they flame across the sky, then suddenly fade into quiet darkness. Movie stars, best-selling authors, and platinum musicians can stay affixed in the firmament of celebrity for decades, twinkling on our Twitter feeds and Entertainment Weekly covers. But years of physical abuse of our bodies through training and competing wears down athletes – and our importance – to stiff, aching, Advil-popping appendages. The useless appendix of the entertainment business. How are we to stay relevant in society beyond yakking endlessly about our glory days?

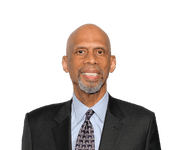

Those glory days for most pro athletes are short. The average career in the NFL is a little over three years. In the NBA, the average it is 4.8 years, and in MLB, it’s 5.6. Most of these athletes have trained for 10 or more years to get to the pros – and for most it’s over quickly. They’ve had a quick taste and are out the door before they become addicted. But for athletes who have managed to beat the odds and stay in the sports spotlight for many years, our final bow can feel a little too final. Kobe Bryant (20 years), Derek Jeter (19 years), John Stockton (19 years), Jack Nicklaus (25 years), Mark Messier (26 years), Nolan Ryan (27 years), Gordie Howe (34 years), Pele (22 years), me (20 years) and many others with double-digit years in the gladiatorial arena are relatively young when we retire, usually in our 30s or 40s. Which is when we ask ourselves the existential question: who am I now?

America does not suffer the aging gladly, even less so the aging athlete. Yes, we are revered for our past accomplishments, praised by fans seeking our autographs, hauled out on camera to compare current players with those from our era. Even with the respectful fuss and sincere deference shown to us, we still feel frozen in time, like frail veterans recounting D-Day, or an old chipped high school trophy lifted from the top shelf and dusted off from time to time for a sentimental flashback. Yet, once we were kings. Microphones were shoved in our faces to record our every word. Children collected our image, wore our player numbers. We were heroes in our ethnic communities as symbols of hope for success and cultural ambassadors to white America. We weren’t just successful, we were significant.

Being significant doesn’t mean being rich. Some athletes retire with millions of dollars, profitable business investments, and a stock portfolio to allow them and their family to live comfortably for generations to come. Some athletes lose millions of dollars and retire to bankruptcy. But almost all end their sports career with a wealth of goodwill from fans that is, to borrow from Proverbs, a price far above rubies. Most of us use that abundance of goodwill for monetary gain in business or entertainment. Some of us will become coaches or commentators, tycoons (Magic Johnson) or movie stars (Dwayne Johnson). Nothing wrong with that. None of us want to end up like Jesse Owens, racing horses for a few bucks, or Joe Louis, broke and collapsing from cocaine use. We are professional competitors, and sometimes winning can be measured in dollars.

But financial success shouldn’t be our end goal. We have the opportunity to use our celebrity to reshape society rather than just entertain it. Some may choose politics: the NBA’s Kevin Johnson and Dave Bing went on to serve as mayor of Sacramento and Detroit respectively while NFL quarterback Jack Kemp served in the House of Representatives for 17 years (there are many other examples). Holding political office isn’t the only way to alchemize celebrity into social change: speaking out and lending your name or presence to social causes you believe in doesn’t diminish your celebrity, but rather gives it meaning because now your name isn’t only related to how well you handled a ball, a bat, or a stick, but how committed you are to a community.

We must remember that the world is not necessarily receptive to athletes – retired or active – speaking out on current events, just ask Colin Kaepernick who finds himself out of a job in the NFL. “Shut up and dribble” reflects the reluctance of some to listen when we express our outrage at police shooting unarmed people of color, bias against immigrants, attempts to block minorities and the poor from voting, and other issues so vital to our society. That’s why it’s important for us to be informed about the topic before we speak on it. We cannot squander the currency of our remaining celebrity by tossing out provocative comments just for entertainment value. We owe our fans, our communities, and ourselves better.

In WB Yeats’ famous poem Sailing to Byzantium, he describes aging into uselessness perfectly: “An aged man is but a paltry thing,/A tattered coat upon a stick…” But he follows that depressing diagnosis with an inspiring remedy: “…unless/Soul clap its hands and sing…” If we tap into the energy and commitment in our souls, we can invigorate ourselves, inspire others, and improve the world we all live in. Then we are more than great athletes, we are worthy human beings.