Cabeza Prieta national wildlife refuge, which includes 56 miles of Sonoran Desert along the US-Mexico border, is a stunningly beautiful wilderness. There are saguaros, endangered Sonoran pronghorn, petroglyphs, and jagged mountain ranges.

It is also where in the past year alone, humanitarian workers have discovered the bodies of 32 people. These remains were found by volunteers from No More Deaths and other humanitarian aid organizations that work to reduce deaths and suffering along the US-Mexico border.

If you go to Cabeza Prieta and walk along its arroyos, chances are you’ll find human remains too. While volunteering for No More Deaths, I’ve come across scattered rib bones, a femur, and a skull resting beneath a mesquite tree, 10 shades whiter than anything else around it.

On 17 January, No More Deaths released a report documenting the systematic destruction by border patrol of water and food supplies left in the desert for migrants. Over a nearly four-year period, 3,856 gallons of water had been destroyed. The report linked to video showing border patrol kicking over gallons and pouring them out onto the ground.

Hours after the report was released, Scott Warren, a volunteer with No More Deaths, was arrested and charged with a felony for harboring migrants after Border Patrol allegedly witnessed him giving food and water to two migrants in the west desert near Cabeza Prieta.

If convicted, he could face five years in prison.

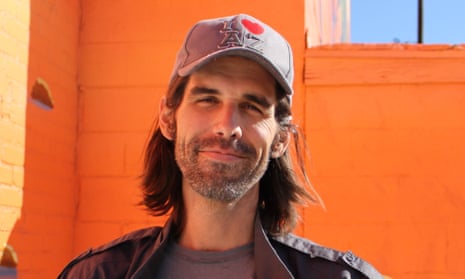

Scott is lanky and soft spoken. He wears worn jeans and a long-sleeve shirt that’s faded from the desert sun. His hands are red with psoriasis and he uses them to tuck an old bandana under his baseball cap to shade his face. He works as a professor of geography at Arizona State University, and he spends the rest of his time here in the borderlands, doing humanitarian aid.

I first met Scott in December of 2016, when I came out to the desert to volunteer. Every day that month, on our trips on rutted jeep roads to put out water for border crossers, things would go wrong; trucks would break down, logistics would unravel, best laid plans would go awry. Through all of these tiny crisis, Scott stayed calm, and full of good humor.

He was so calm that I often didn’t know, until afterwards, how sketchy a situation had really been – how close we’d come to disaster. I learned to appreciate Scott’s inexplicably calm goodwill as the sort of eye in a hurricane- when it felt as though everything was spiraling into chaos, I only had to look at Scott to be reminded that somehow, some way, everything would turn out fine.

Scott talked to me after I found my first set of human remains, and was so upset that I couldn’t stop crying. He told me that once he’d walked out into the desert at night, just to see what border crossers saw. He’d been overcome with the loneliness of that great emptiness, and he’d looked up at the stars and thought about how these same stars were the last thing that many people saw before they died, in an arroyo or under a palo verde tree, hundreds or thousands of miles away from the people that they loved. Then he’d laid down in the dirt, in the dark desert, and he’d wept for a long time.

Cabeza Prieta is possibly the most remote and inaccessible area in which No More Deaths provides humanitarian aid. Its inaccessibility is also one of the reasons why the area is so deadly – if one walks north through the Growler valley, in which the bulk of the human remains have been found, it is 20 miles as the crow flies from a rough dirt road in the south, known as the Devil’s Highway, to the next exit point, a rutted four-wheel drive road at Charlie Bell Pass.

In between these two remote tracks, there is only the flat, baking Growler Valley, where summer temperatures soar above 115F (46.1C), and winter nights are cold enough to give a person hypothermia. Running north-south alongside the Growler valley are the Growler mountains, whose impassible ridgeline prevents escape to the Childs valley to the east.

Once you’re in the Growler valley, you’ve committed – there is no way out, no water, and no way to be rescued should you need help.

One’s journey through this area can be interrupted for all sorts of reasons: a sprained ankle from falling into an arroyo while hiking at night, delirium from heat exhaustion, border patrol scattering your entire group via helicopter and leaving you lost and alone. And if you stop walking in the Growler valley, you’ll die.

In the last year, No More Deaths has been slowly increasing their efforts to get water into Cabeza Prieta. This is no easy feat. You can walk five miles from the nearest public road carrying six gallons of water in the heat, and still be barely within the perimeters of this vast desert wilderness.

It was on these forays that Scott, as well as other No More Deaths volunteers, began to find the human remains. What seemed an anomaly at first soon showed itself to be a crisis of epic proportions: the volunteers were routinely stumbling on human remains.

As No More Deaths stepped up their efforts, so too did Border Patrol and the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Not to prevent death or to recover human remains, but to criminalize humanitarian aid.

In the summer of 2017, eight volunteers were charged with federal misdemeanors related to No More Deaths providing humanitarian aid in this area. Many more volunteers had their permits to Cabeza Prieta revoked indefinitely.

Around the same time, a new clause appeared on the permit application for access to Cabeza Prieta. Clause 13 states that the holder of the permit will not leave food or water in the desert, effectively preventing humanitarian aid in Cabeza Prieta entirely.

Border Patrol policy has turned the desert into a weapon. This specific policy is called “prevention through deterrence”, and was enacted in 1994. Before the policy, a person could cross the US/Mexico border relatively safely, from an urban area into an urban area. With prevention through deterrence, urban areas were walled off, forcing border crossers into the harshest and most remote parts of the desert. Checkpoints were placed on roads as far as 100 miles north of the US/Mexico border, so that once in the waterless desert wilderness, those crossing were made to walk for weeks in order to get around these checkpoints.

The US/Mexico borderlands had been restructured as a deathtrap, and it worked – while the number of people crossing went down, death in the desert soared, and continues to rise each year. In the last two decades since prevention through deterrence was enacted, more than 7,000 thousand sets of human remains have been recovered in the US borderlands.

When I last talked to Scott he was in good spirits, in spite of his felony charge and pending trial. Scott puts water and food in the desert where people might die without it otherwise, and he knows that this is the right thing to do.