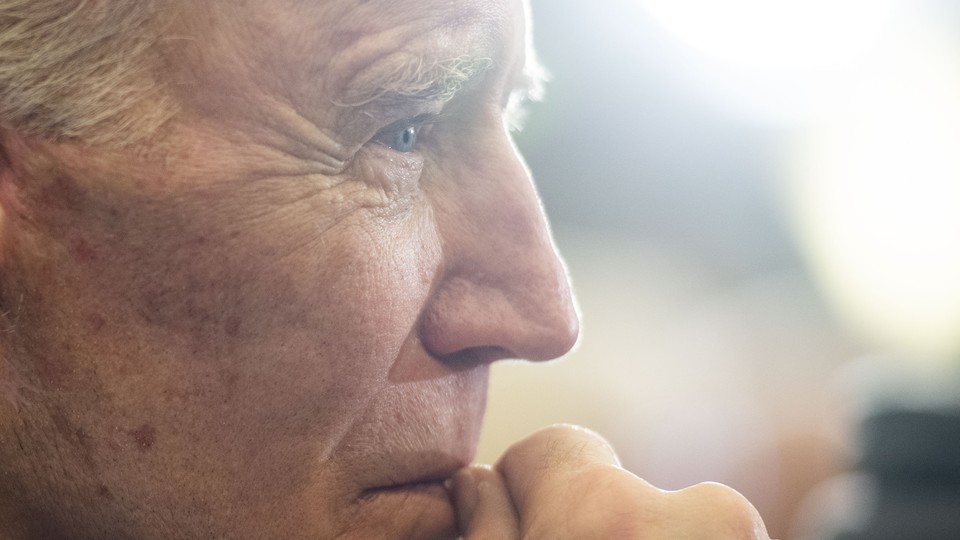

WEST DES MOINES, Iowa—The Friday night before the Iowa caucus, John Kerry was standing on the sidewalk in front of Joe Biden’s campaign headquarters, wearing a bomber jacket and a pale-blue scarf, insisting that everything was about to snap into place for the former vice president. That’s why so many people were going into the caucus saying they were undecided, he argued.

“Some people have been torn between the idea of, you know, new, fresh, whatever, versus somebody with experience, and they're trying to wrestle with it,” he told me. “But I think in the end, people are now coming to the conclusion Joe Biden is best situated to win, best situated to contest in areas where we need to bring congressmen and senators with us.”

Two days later, Kerry was caught musing on a telephone call about what it would take to get him to jump into the race himself. The voting hadn’t even happened yet.

Biden and his aides have long insisted that they were totally fine with how few people were showing up to see him. They were not. They tried to fill the rooms. It didn’t work. They learned to accept that the crowds would never come, and tried to build a campaign around never getting them.

They failed.

Neither the disaster of the Iowa Democrats’ caucus app nor the reporting delays change the reality: The former vice president of the United States and the front-runner in nearly all the national and Iowa polls came in a distant fourth, behind Bernie Sanders, Pete Buttigieg, and Elizabeth Warren. Now he must struggle to reassert himself and hope for a magical underdog story (hey, Bill Clinton turned himself into the Comeback Kid after placing second in the 1992 New Hampshire primary). But forget about advertising and campaign staff: It’s now an open question whether Biden will have the cash to pay for his charter plane to fly him around the 14 Super Tuesday states that vote on March 3.

Running short on money is a big part of why he ended up here at all.

After a disastrous summer of fundraising, plans from the team in Iowa and other states would linger with national headquarters for weeks, then come back without approval for the spending being requested. Other candidates were quickly hiring staff—particularly Buttigieg, who in June had all of four staffers in the state but went into the caucuses with 170—while Biden’s team was under an almost complete hiring freeze. The campaign yanked its TV ads, leaving Biden dark for weeks and exponentially outspent in online advertising by Warren and Buttigieg, who soon had the rising poll numbers to show for it. At one point, aides realized, Biden was on track to spend less on TV in Iowa in this race than in his 2008 run, when he finished as an asterisk, with 1 percent of the vote.

Biden aides who were being honest with themselves knew for months that they were in trouble. Some didn’t want to believe it; some couldn’t. Others felt like they’d gotten into a taxi with a driver who was swerving all over the road, and they were just holding on and hoping they made it to the end.

They hoped that Democrats’ obsession with beating Donald Trump and voters’ sense of personal connection to Biden would pull them over the edge. Trump had blundered into his own impeachment out of fear that Biden was strong. Now they were hoping the impeachment trial would help make up for his weakness. “We might win this,” one person who worked on the campaign told me the week before the caucuses, “and it might come down to nothing we’ve done.”

When Biden held his final pre-caucus rally at a middle school in Des Moines on Sunday afternoon, 1,100 people came—his biggest crowd in Iowa of the whole campaign. Eight people introduced him; four retired senators were in the crowd. But by the time he began speaking, the Super Bowl had started, and people were dribbling out of the room. An hour earlier, a few miles away in a high-school gym, Buttigieg had drawn twice as many people.

[ Peter Beinart: Impeachment hurt somebody. It wasn’t Trump. ]

Biden himself has never been fine with how his campaign has been going, and he’s never been the serene-to-the-point-of-oblivious presence that his aides have made him out to be. Increasingly concerned about the day-to-day management of the campaign by junior aides, he turned to his older inner circle. They settled into a war-weary resilience. “There’s no joy in the campaign,” one Iowa Democrat who’s been watching the race closely told me ahead of the vote. People working for the campaign made the same point to me, though usually with more curses.

Biden’s late start, and his need to host high-dollar fundraisers in Los Angeles, New York, and Washington, D.C., limited the amount of time he spent on the ground in Iowa. So he rarely made the kind of traditional stops, like going table-to-table in restaurants, where his last-of-his-era, retail-politics virtuosity shines.

[ Read: Joe Biden is Schrödinger’s candidate ]

By leaving up to an hour after each event for Biden to shake hands and take selfies—real selfies, aides would often pointedly note, with the candidate holding up phones himself, in contrast to the posed shots Warren takes on her “selfie lines”—they came close to their internal goal of having him personally meet 20,000 Iowans. Other candidates went for big rallies to feed news coverage, they felt, but they’d given up on ever getting the coverage they thought Biden deserved, and focused on small rural areas where having even just a few dozen supporters could deliver them delegates.

Whatever big ideas the campaign seemed to have were mostly swiped from previous campaigns, like identifying veterans by pulling county-by-county records of who’d qualified for a special state tax credit (a Kerry move in 2004). They deployed Jill Biden, by far the best-known candidate’s spouse, as part of a dedicated appeal to teachers. They sought out independents and disaffected Republicans, targeting them with messages that portrayed Biden as a statesman, in contrast to Donald Trump. They chased Catholics (“Consistent with the highest traditions of Catholicism, Joe Biden has demonstrated his belief that we have a shared obligation,” the former ambassador to Ireland declared in a handwritten letter that was copied and mailed to thousands of homes). They turned to paid workers, rather than relying on volunteers, to knock on the doors of African American and Latino voters—although they did bring in hundreds of volunteers for the final few weeks (with logistical stumbles, such as failing to tell some of the people who’d agreed to house those volunteers when their guests would be arriving). They pressed, at every turn, a message of restoring national unity that resonated more with voters than it ever did with reporters or pundits. They emphasized Biden’s character. They insisted everything was fine.

They flubbed basics. On Monday, standing at a caucus site at a Holiday Inn just 15 minutes from Biden’s campaign headquarters, I watched the Biden precinct captain stand around somewhat helplessly as the few people Biden would have needed to clear the viability threshold were instead courted successfully by Amy Klobuchar’s team. She won a county convention delegate. Biden won nothing. Afterward, the precinct captain told me that he’d come in from California, and didn’t really know the area or anyone in the room. “Sometimes you get a particular area that is to the left,” he said with a shrug. People at the homes whose doors he’d knocked on had told him they weren’t going to come caucus, because they assumed “Biden’s going to be fine; he’ll probably be the nominee.” He told me he had noticed the enthusiasm for Buttigieg, though.

Before this week, October was the low point, punctuated by the smack of the first Des Moines Register poll showing him tumbling and Warren in the lead. Biden was being out-organized, outworked, and, most of all, outspent. His late entrance in the race kept coming back to haunt him: He didn’t have a cushion of campaign cash; he hadn’t locked up top operatives anywhere.

[ Peter Beinart: When the staff can’t tell the candidate what’s wrong ]

November 1 found Biden in Des Moines for the biggest primary event of the year: the Iowa Democratic Party’s Liberty & Justice Dinner, where all the candidates were speaking, and all their teams were organizing major shows of force to strut for the press and the local party bigwigs. Buttigieg went first, and he was smooth, claiming Barack Obama’s legacy as his own. But more important than anything he said was what he looked up at: sections of the arena packed with supporters wearing yellow T-shirts, their light-up wristbands flashing as they waved their signs.

Biden spoke second, right after Buttigieg. Some watching him closely from the audience swore they could see his attention drifting to the hundreds of empty spots in his reserved sections. They were right.

The next few weeks were a scramble. Just in time, money started coming in from big donors spooked by Warren’s strength and in response to the impeachment inquiry, which the Biden campaign moved aggressively to turn into proof that Democrats should see him as the strongest candidate against Trump. Headquarters rushed Biden’s ads back onto the air. The campaign started hiring again. Aides planned more trips to Iowa. A bus tour was a massive success. Big-name endorsements that had been kept in reserve for months, like Kerry’s, were rolled out.

But Sanders was creeping up in the polls, and Biden aides weren’t quite sure what to do about that. “I don’t respond to Bernie,” Biden told reporters after opening an office in Cedar Rapids at the beginning of January, although three weeks and a bunch of new polls later, Biden was suddenly on the attack, mockingly saying that Sanders’s position on Medicare for All was “I don’t know how much it’s going to cost, but we have to do it.” The Thursday night before the caucuses, at the American Legion hall in Ottumwa, asked by a reporter about the Sanders campaign circulating a video in which Biden seems to be advocating for Social Security cuts, Biden reached into his jacket pocket and handed him a prewritten statement with the header “BERNIE FALSE ATTACK ON SOCIAL SECURITY.”

As Biden’s Iowa campaign drew to a close, I kept thinking back to the first weekend in January. That Saturday night, Biden drew 750 people, and his aides couldn’t stop buzzing. The next night in Davenport, the campaign set up 87 chairs on the third level of the Minor League baseball stadium, and lit up as they watched the room get packed with 450 people. Someone had to open the windows to the cold air outside. Never mind that a 10-minute drive away, two hours earlier, Warren had drawn 650 people, who left more visibly enthusiastic and committed.

Before that event, I started chatting with a man named Bill Wilson, who told me that he’d started out intrigued by John Delaney’s approach, but that the only candidate he’d donated to was Senator Cory Booker, whom he called “inspirational.” He worried about losing to Trump, but he also worried about Biden’s vote for the Iraq War, among other things. After Biden’s speech—a long but reasonably put-together riff on his usual stump speech that touched on Trump’s standoff with Iran (“a crisis of his own making”)—Wilson caught my eye to update me. Now, he said, he was going to send some money to Biden. “He might get elected, but next time, probably not,” Wilson told me. “I think he’ll have probably the one term. But that might be enough to get us stable.”

Biden insists he’s more durable than that. His aides say he’s stronger than he was the day he entered the race last April, and it doesn’t matter that he came in fourth, or that he seems to be in trouble in New Hampshire too.

“What voters are seeing is somebody who can take Trump’s punch because he’s known, because people have a sense of who he is,” a deputy campaign manager, Kate Bedingfield, told me. “That’s the way to beat Trump. That’s the key. You’ve got to put somebody up against him who’s impervious.”

Is he?