How the Republican Majority Emerged

Fifty years after the Republican Party hit upon a winning formula, President Trump is putting it at risk.

In July 1969, Kevin Phillips, a 28-year-old staffer in the Nixon White House and special assistant to Attorney General John Mitchell, published a book boldly titled The Emerging Republican Majority. For nearly four decades, the Democratic Party’s New Deal coalition had dominated American politics. But in the book, Phillips argued that the old order had come to an end, and that a new conservative era was in the offing.

Nearly 500 pages long and filled with facts, figures, and maps, The Emerging Republican Majority contended that the GOP needed to move beyond its traditional base in the Northeast and reach out to white voters in the South and Southwest—a region Phillips dubbed the “Sun Belt”—and in suburbs across the nation with polarizing appeals on racial and social issues. The book attracted significant attention, appearing in bookstore windows nationwide. Newsweek christened it “the political Bible of the Nixon Era,” while National Review called it the most important political book in the generation.

The Emerging Republican Majority has loomed large in the minds of political operatives and observers ever since, as an essential guide to the Republican “southern strategy” that gave modern conservatism the depth and durability of New Deal liberalism. For his part, Phillips always insisted this was a misreading. “The book was not and is not a ‘strategy,’—Northern, Southern or Western,” he noted in the preface to the 1970 paperback edition. “The book is a projection—and one with a high batting average to date. Read it as such.”

In truth, it was both. Phillips’s projection was grounded in his assessment of recent Republican strategies. At the same time, he asserted that his analysis offered the best hope for the party’s future: pitting racial and ethnic groups against one another and capitalizing politically on the competitions and resentments that followed. “The whole secret of politics,” he told the journalist Garry Wills during the 1968 presidential campaign, is “knowing who hates who.”

That year, the GOP had convincing reasons for following Phillips’s lead. The segregationist Governor George Wallace made a strong showing in the South and elsewhere with a shoestring campaign as an independent, demonstrating that opposition to integration played well with some working- and middle-class white voters. Phillips saw the potential: If Republicans exploited tensions over civil rights, he argued, they could attract white voters in traditionally Democratic southern states, as well as in the Midwest and West. And if Republicans won those voters, they’d win the mantle of power too.

Fifty years later, it’s tempting to draw a straight line from The Emerging Republican Majority to the Republican Party today. The GOP has come to dominate every part of the Sun Belt, just as Phillips predicted, and President Donald Trump has mobilized the politics of division in a way no modern president has before. “Objects in the mirror really are closer than they appear,” Louis Menand wrote in The New Yorker last year. “It’s not that far from Wallace to Trump.”

But a closer look at the initial reception to The Emerging Republican Majority shows that the line to Trump is less clear. Despite Phillips’s position in the Nixon White House, administration officials were deeply divided over the book’s recommendations. Nixon had won the Republican nomination by forging a centrist path between the liberal Nelson Rockefeller and the conservative Ronald Reagan, and then won the presidency by similarly positioning himself between the liberal Democrat Hubert Humphrey and the conservative populist George Wallace.

Moving to the right on racial and social issues seemed risky to many in the Nixon camp, but some enthusiastically supported the idea. The administration waffled between right and left for two years, but in the 1970 midterms went all in with a strategy to exploit racial and social divisions in campaigns across the Sun Belt. Phillips’s critics turned out to be right: The results were dismal. When Nixon acknowledged as much after the election, he promised to pull himself back to the center.

But the strategy didn’t die with Nixon. It would be revived, combined with a new emphasis on social issues, and used to great success in the 1980s to secure the Republican majorities that Phillips had prophesied. Now President Trump is exploiting racial and social divisions even more aggressively than did Nixon in the 1970 election—and in the process, he risks consigning Republican majorities to the past.

At its core, The Emerging Republican Majority called for a literal redrawing of the electoral map. The two parties had, with few exceptions, claimed different corners of the country for the better part of a century: Democrats in the “solid South” of the former Confederacy, and Republicans in the old Union of the Northeast and Midwest.

But Phillips argued that these territorial tendencies were fading, and urged Republicans to work harder to speed their disappearance. “The Civil War is over now; the parties don’t have to compete for that little corner of the nation we live in,” the Republican analyst told a reporter in New York. “Who needs Manhattan when we can get the electoral votes of 11 Southern states?”

The idea of swinging the South to the Republicans was not Phillips’s invention, as he readily admitted. White southerners had been drifting away from their traditional party ties for decades. In the late 1930s, southern Democrats in Congress had forged a “conservative coalition” with like-minded Republicans to fight New Deal liberalism. Despite this working alliance, southern Democratic congressmen remained in the party—not least because Democrats dominated Congress and, as a result, their seniority within the party guaranteed them a good deal of power in the committee system. But the “Dixiecrat” rebellion of 1948, led by South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond, showed that party ties weren’t permanent*. In that campaign, southern officials and ordinary white southerners alike began to abandon the Democrats over civil rights.

Republican leaders saw an opening. Guy Gabrielson, the chairman of the Republican National Committee from 1949 to 1952, hoped to bring disaffected Dixiecrats into the GOP. “The Dixiecrat Party believes in states’ rights,” he told an Alabama gathering in 1952. “That’s what the Republican Party believes in.” Seeking to craft a coalition of southern Democrats and northeastern Republicans, Gabrielson commenced negotiations for what he called a “trial marriage at the top” in which nominally independent Dixiecrats would pledge to support the Republican nominee in 1952. Gabrielson’s scheme never came to fruition, but the GOP nominee still cracked the solid South: Dwight Eisenhower won three southern or border states in 1952 (Florida, Tennessee, and Virginia) and five in 1956 (Florida, Tennessee, Louisiana, Kentucky, and Virginia).

As he prepared for his own run for president, Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater likewise tried to bring white southern conservatives into the Republican fold. But rather than proposing a partnership between the South and the Northeast, Goldwater wanted to connect southern Democrats with libertarians and conservatives in the Southwest and West. In a 1961 speech to southern Republicans in Atlanta, Goldwater famously declared that the GOP should “hunt where the ducks are” by writing off “the Negro vote” and pursuing southern whites instead.

Capitalizing on the white southern backlash against civil rights was central to this strategy. But by the mid-1960s, overt racism was an ineffective method of courting southern voters. The region’s most successful politicians adopted more muted appeals to racial issues, and Goldwater proved to be a skilled practitioner of this approach. Instead of “direct racist appeals,” he used “a kind of code that few in his audiences had any trouble deciphering,” noted The New Yorker in 1964.

In making federal involvement in social, cultural, and economic issues the ostensible focus of his opposition, rather than race itself, Goldwater managed to reassure the South that he would protect the status quo while simultaneously appealing to the libertarian sensibilities of the West and Southwest. “I believe that it is both wise and just for Negro children to attend the same schools as whites,” Goldwater wrote in The Conscience of a Conservative. “I am not prepared, however, to impose that judgment of mine on the people of Mississippi or South Carolina … Social and cultural change, however desirable, should not be effected by the engines of national power.”

Goldwater lost the 1964 election in a national landslide to Lyndon Johnson, but the election returns showed a silver lining for the GOP. Aside from his home state of Arizona, the only states Goldwater won were in the Deep South—Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and Louisiana.

While Eisenhower had made inroads in the South by adding states from the region’s edges to his national coalition, Goldwater focused on the “ducks” of the Deep South, and with convincing results. Mississippi’s path was instructive: While GOP nominees had won less than 25 percent of the state’s vote in 1956 and 1960, Goldwater took a whopping 87 percent in 1964. Moreover, his southern coattails helped elect a new generation of Republican congressmen, whose vocal opposition to civil rights had been the centerpiece of their own campaigns. (In an extreme example, Prentiss Walker, the first Republican congressman from Mississippi in a century, celebrated his 1964 victory with an appearance before a Ku Klux Klan front called Americans for the Preservation of the White Race.)

The results were clear: The South was ripe for Republicans.

Kevin Phillips studied these returns obsessively, concluding that many white voters in the Southwest and in the suburbs shared with the white voters of the South an uneasiness with civil-rights advances and growing African American political power. The “principal cause of the breakup of the New Deal coalition,” according to Phillips, was the “Negro problem.” If Republicans could capitalize on that racial tension, their party would profit.

Phillips was not interested in a partnership between estranged Democrats in the South and Republicans in the North, which Gabrielson had imagined 20 years earlier. The old Republican establishment of the Northeast, Phillips argued, was crumbling as a result of its acquiescence to liberalism. Rather than including the Northeast in an electoral coalition, Phillips argued the region was most useful as a “provocateur of resentment elsewhere.”

Instead, Phillips called for uniting the South and West, as Goldwater had hoped, while also appealing to another group: the growing suburban electorate. The key to wooing white voters in the Sun Belt, according to Phillips, was taking advantage of “group animosities” and exploiting racial tensions—once again, knowing “who hates who” and acting on it. “Ethnic and cultural animosities and divisions exceed all other factors in explaining party choice and identification,” Phillips observed.

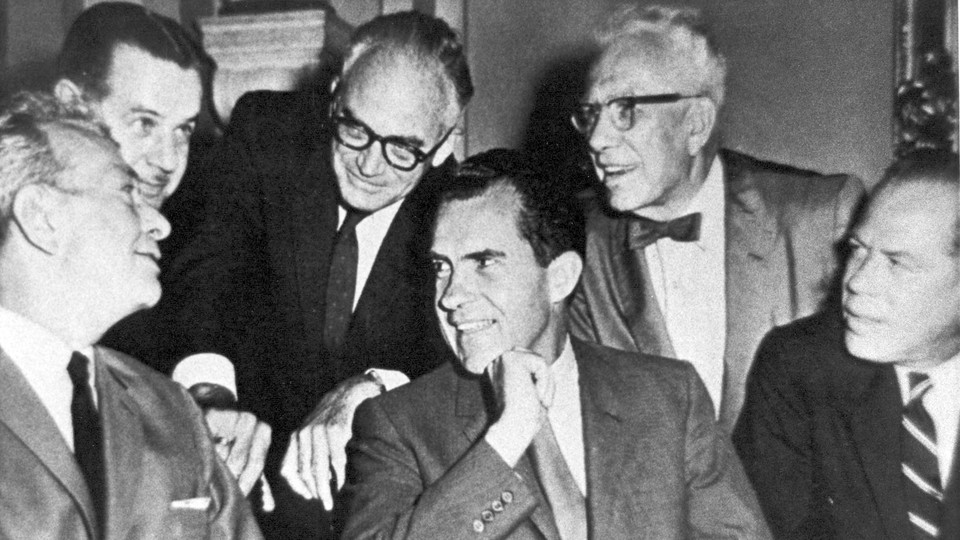

Phillips’s research landed him a role in Richard Nixon’s 1968 presidential campaign. Leonard Garment, one of Nixon’s liberal-leaning advisers, recalled hiring the young man “after scanning a manuscript Phillips had handed me in lieu of a resume. Something called ‘The Emerging Republican Majority.’” Phillips used his research to frame a Goldwater-like strategy that indirectly appealed to racial resentment through criticism of the federal government and an emphasis on law-and-order politics. “The fulcrum of re-alignment is the law and order/Negro socioeconomic syndrome,” Phillips wrote in one 1968 campaign-strategy memo. “[Nixon] should continue to emphasize crime, decentralization of federal social programming, and law and order.”

Nixon’s 1968 campaign emphasized the need to roll back Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society liberalism and embrace a tougher law-and-order attitude toward urban riots and anti-war protests. His championing of a “silent majority” that had grown tired of protests for civil rights and other causes helped him win over much of the upper South, taking five states back from the Democrats. The independent candidacy of the Alabama Democrat George Wallace, who won five southern states that year, stymied Nixon’s effort to replicate Goldwater’s success in the Deep South.

Phillips wasn’t deterred. He argued that Wallace’s independent run, like the Dixiecrat campaign before it, was simply a “way station” in the migration of white southern conservatives. They had left the Democrats for good and would soon join the Republicans. “We’ll get two-thirds to three-fourths of the Wallace vote in nineteen seventy-two,” he confidently predicted.

Although Phillips dedicated The Emerging Republican Majority to President Nixon and Attorney General Mitchell, few in the administration wanted to associate themselves with the book.

When it was published, just seven months after Nixon’s inauguration, heavyweights in the Nixon White House pushed back. The speechwriter William Safire called the book “dangerous,” noting that a “tacit ‘writing off’ [of] any area is a big political mistake.” Even Nixon’s southern strategist, Harry Dent, a former aide to Senator Thurmond, warned against acknowledging the shift in regional priorities. “We should disavow Phillips’ book,” Dent wrote Nixon, “and assert we are growing in strength nationally.”

In its first year, the Nixon White House constructed a centrist image by coupling a host of conservative initiatives with a handful of liberal-leaning ones. This approach was clearest on civil rights, where the administration deliberately sent different signals to different constituencies. Nixon nominated to the Supreme Court two white southerners who had, to varying degrees, resisted civil rights, for example, and when the Voting Rights Act of 1965 came up for renewal, Mitchell testified against it. But at the same time, Nixon and Mitchell worked to ensure the peaceful integration of the last southern school districts that were still segregated.

The administration deliberately “furnish[ed] some zigs to go with our conservative zags,” the domestic-policy chief John Ehrlichman reminded the president. He pointed to the administration’s support for affirmative action in the “Philadelphia Plan” as an example. On the surface, Nixon’s support seemed out of step with his campaign promises; the Philadelphia Plan stemmed from one of LBJ’s most aggressive civil-rights policies. But Nixon’s aides saw it as a way to fracture the New Deal coalition by pitting civil-rights organizations and labor unions against each other. “Before long,” Ehrlichman later chuckled, “the AFL-CIO and NAACP were locked in combat over one of the most passionate issues of the day, and the Nixon administration was located in the sweet and reasonable middle.”

In contrast to this zigging and zagging, Phillips urged a clear move to the right on racial and social issues. “If you intend the pure conservative line which Phillips peddles,” a confused Ehrlichman told the president, “someone had better straighten me out.” Safire similarly argued that the administration “belong[ed] in the center with a solid appeal in both directions.”

But some of Nixon’s advisers welcomed Phillips’s call for a starkly regional strategy. The speechwriter Pat Buchanan called Phillips “a genius of sorts,” while a young Nixon operative named Tom Huston argued that Phillips was right about what made certain constituencies tick. The blue-collar white worker, Huston said, “fears that blacks are going to take his job, or move into his neighborhood, or beat up his kids at school.” (A few years later, Huston became infamous for devising a plan to spy on Nixon’s political enemies, which ultimately contributed to the unfolding of the Watergate scandal.)

In the short term, Phillips’s preference for polarization won out. The administration redoubled its efforts across the Sun Belt to win over white conservatives who had previously left the Democrats for Goldwater, Wallace, or both. To do so, they borrowed heavily from the Wallace playbook, pressing the racial issue bluntly. “I wish I had copyrighted my speeches,” Wallace marveled in 1969. “I would be drawing immense royalties from Mr. Nixon and especially Mr. Agnew.”

But the results of the 1970 election showed that Phillips had misread the tea leaves. Democrats held control of both houses of Congress, picking up a dozen more seats in the House, while the Republicans picked up only two seats in the Senate. Nixon realized the strategy had failed. “We probably went too far overboard,” he conceded in a 30-page analysis he sent to his chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman. Changing tactics, Nixon suggested more outreach to minorities, workers, and the young. “I ought to have symbolic meetings with all types of minority groups,” he wrote, emphasizing “the need of the President to be at least appearing to make an effort to communicate with all segments of the society.”

But Nixon still sought to win over white voters. When busing emerged as a divisive civil-rights issue, Nixon exploited it for all it was worth, even having Assistant Attorney General William Rehnquist draft a proposed constitutional amendment to outlaw the practice. When career lawyers in the Justice Department promoted busing, Nixon came down hard on them. “Knock off this crap,” he wrote Ehrlichman in 1971. “I hold [department heads] accountable to keep their left wingers in step with my express policy.” When two more vacancies opened up on the Supreme Court that year, Nixon instructed his attorney general that the nominee had to be “against busing and against forced housing integration. Beyond that, he can do what he pleases.” Not surprisingly, one of the two spots went to Rehnquist.

With this strategy—a subtler appeal to the resentments of whites in the Sun Belt combined with some centrist policies, and even an effort to court minorities—Nixon won the 1972 election in historic fashion. His 60.7 percent of the popular vote was the third-largest share of any presidential contest in the 20th century, behind only Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1936 and Lyndon Johnson in 1964.

Phillips considered the election a vindication of his work. He had dismissed the 1970 midterm results, noting at the time that his strategy was “a presidential strategy [that] does not apply in off-year elections.” But 1972 counted, and in that race, Nixon won every single state in the Sun Belt (along with everything else).

The Republican majority seemed to have finally and fully emerged.

Any vindication Phillips felt at Nixon’s national landslide was short-lived.

The Republican Party suffered devastating losses in the midterm election of 1974, partly because of the backlash over Watergate, the resignation of Richard Nixon, and President Gerald Ford’s controversial decision to pardon him. The GOP’s gains in the South were abruptly reversed in the next presidential election, when Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter reclaimed every southern state except Virginia for the Democrats.

As the Republican Party’s fortunes soured, conservatives soured on Kevin Phillips. “There is an eccentric theorist writing orotund stuff about major trends in American politics,” William F. Buckley Jr. noted in 1975. “His name is Kevin Phillips. A few years ago, he wrote a book called The Emerging Republican Majority, which was a most fascinating volume, suffering only from the massive inaccuracy of its predictions.” James Burnham, an editor at Buckley’s National Review, was even more dismissive. “As things turn out,” he noted ruefully in 1976, “it is Jimmy Carter who seems to be putting the majority together under Democratic auspices.”

But Republicans would not have to mourn for long. Throughout the 1980s, GOP nominees racked up massive victories, with the South emerging as the party’s most reliable region. Reagan took every state there in 1980, save Carter’s Georgia, and then Reagan, in 1984, and George H. W. Bush, in 1988, won the entire South. Democrats pushed back in 1992 and 1996, with Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton and Tennessee Senator Al Gore Jr. at the top of the ticket, but Texas’s George W. Bush reclaimed the entire region for Republicans in 2000 and 2004.

As the Republican majority took shape in these decades, its architects insisted publicly that their work had nothing to do with the blueprint in The Emerging Republican Majority—distancing themselves from Phillips’s work, much as the Nixon administration itself had done. In a 1981 interview, the Republican strategist Lee Atwater insisted that the Reagan campaign had been a stark departure from “the old southern strategy,” which, in his words, had been “based on coded racism.” The Reagan blueprint was based on appeals to economics and national defense, Atwater argued, with race relegated to “the back burner.”

But a closer look at Republican strategies in this era dispels Atwater’s claims. As the political scientists Angie Maxwell and Todd Shields chronicle in their new book, The Long Southern Strategy, the old “coded racism” continued, but in concert with newer appeals to religious conservatism and anti-feminism. (Atwater himself offered something of an apology for some of those tactics toward the end of his life.) Taken together, these approaches solidified the South for the Republicans and, as a result, secured their victories in national races.

Notably, the Republican majority that emerged in these decades did so largely on the terms set forth by Phillips. Appeals to racial resentments, handled lightly, did much of the work, but the broader social issues ultimately played an even more important role. Striking a delicate balance between the two proved to be the winning strategy for the GOP.

The risk for Republicans today, of course, is that President Trump has upset this balance, rejecting old dog whistles on race for full-throated racism. Unlike Nixon, who disastrously tried such a strategy in his first midterm but then dialed it back considerably in his reelection run, Trump has doubled down on the race-based themes that failed to work in his own first midterm. In doing so, he runs the risk of reversing decades of work and rendering the Republican majority a thing of history.

*A previous version of this article stated that Strom Thurmond was a senator in 1948.