The Rise of Video Game Art

One of the exciting art explorations which came out of the digital culture is video game art, an interesting form of interactive computer art based on video game designs. From the dawn of computer culture, which developed behind closed doors at MIT and Department of Defense in the US in the middle of the 20th century, artists around the globe have followed closely and with interest the possibilities of emerging technologies, whether we are talking about the Internet, virtual reality, AI or biotechnology. It was no different with the diverse and successful world of videogames; this huge gamer industry amounted to 60 billion dollars a year in 2012, steadily growing until today, and gave birth to pop subculture of millions of faithful followers with a rich world of festivals, sporting events and online communities, pushing the possibilities of technology ever further. What most people see as simple leisure activity inspired artists to once again put to question the very meaning of Art.

But video games have one more significant connection with digital art, and that is the experimentation with human-computer interface, interactivity and aesthetics of computer image, which contemporary forms of interactive art adopted and continued developing later on. We will explore how famous arcades like Space Invaders and Super Mario Bros, first-person shooter games like Quake and Doom, early adventures like The Legend of Zelda, but also the Massively multiplayer games (MMOGs) and Massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) like Second Life and The World of Warcraft provided a base for artistic performances, original forms of game design and interesting possibilities for collaboration and communication.

What is Video Game Art ?

So what exactly is video game art? And how is it different from the massive creative production of games already considered art in its own right? Although there are many sources online that show us a rich visual art and prints depicting gaming culture, video game art is something entirely different. Though the first work to belong to this genre was Moondust from 1983, it was the 1990s when art producers started experimenting with computer and internet technology in larger numbers. Video game art developed as a subgenre of new media art, tied closely with net art, interactive and software art, as well as virtual communities popular in the last decade of the 20th century. These artists use code, gameplay and interactive design tools to provoke a reaction and communicate their ideas, and in this sense, video game art, like most new media art, found its precursors in the great avant-garde and conceptual art movements. For its serious intent, such artwork is also recognized by thriving serious games industry as its own subgenre - that of Art Games, stressing activist and educational aspects of artworks.

Following the variety of game types already existing, video game art includes several distinct forms. Most common are perhaps the pieces which present ether original game design or copy existing video games, usually classic works like Space Invaders from 1969, or 1985 Nintendo Super Mario Bros. Also found often are the so-called Mods or artistic modifications of video games. Here, artists use coding skills to leave their mark within games, making changes to the design usually with some critique in mind. In a similar fashion, some use their skills to create pieces which are performances in gamespace. Usually being staged in popular multiplayer games like Second Life, performers transform the player community into an audience for their projects.

Artists Making Video Games

The reason art creators were attracted to video games in the first place was their ability to broaden storytelling - getting the opportunity to engage the viewer in a truly active manner and at the same time controlling their experience. By entering the gamespace, the player is more often than not diverged from traditional goals, like passing to another level, or just having fun. This is maybe the crucial difference between video game art and gaming in general. Everything in a video game artwork is designed to inspire us to think, to question what we experience and why, both inside the gaming culture as well as out. In most cases they look quite different than what we imagine when talking about video games in 2017. Creating commercial games is a serious business, with entire armies on the payroll and months of production, while creating video game artwork is usually a modest affair, happening on home computers within small teams.

Women Artists in the World of Gaming - Natalie Bookchin’s The Intruder

Brooklyn-based artist Natalie Bookchin’s net based work titled The Intruder was created in 1999, based on a story by Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges of the same name. Her interactive narrative game is conceived as a feminist critique, changing Borges’s text so that the woman is seen as an intruder in a man-made world, but also in the gaming sphere. Taking us through ten short classic videogames similar to Pong, Space Invaders and old Atari and Nintendo arcades, throughout some 15 minutes gameplay the accent is put on uncovering the narrative, making playing secondary to the experience.

Natali Bookchin – The Intruder (Documentation), 1999

Radical Games of Paolo Pedercini – Molleindustria

Italian artist Paolo Pedercini's project The Molleindustria introduces a call for re-articulating popular gaming culture as radical social action through a concept of Soft Industry, as a call to arms against contemporary entertainment industry. Starting from 2003, the artist has been presenting series of simple, yet authentic free online videogames for Mac, Windows and Linux, designed to tackle a specific social issue: Nova Alea, a game about cities and those who rule them, Oligarchy, on the dark issues of oil drilling, or The Free Culture Game which invites us to help defend freedom of knowledge in the age of copyright. Like many other creatives in computer-based art, Pedercini doesn’t really see his work as Art per se, but cross-pollination of worlds inviting discussion and action on social and technological issues.

Mods - Artistic Modification of Video Games

One particularly interesting form of video game art drove artists into a conceptual re-appropriation of already existing gamespace. Mods or modifications refer to visual and narrative changes inserted in games via patches, pieces of software usually created by programmers for the purpose of fixing or improving the game. In the context of video game art, these extensions allow players to enjoy different gameplay, whether by creating simple character skins or producing brand-new games by altering the code of the original. These kinds of interventions were already a significant part of the gaming subculture, prominent in games like Half-Life, Minecraft and Grand Theft Auto. Through game modifications, artists found means not only for disseminating their ideas, but for using virtual environments to frame those ideas as well.

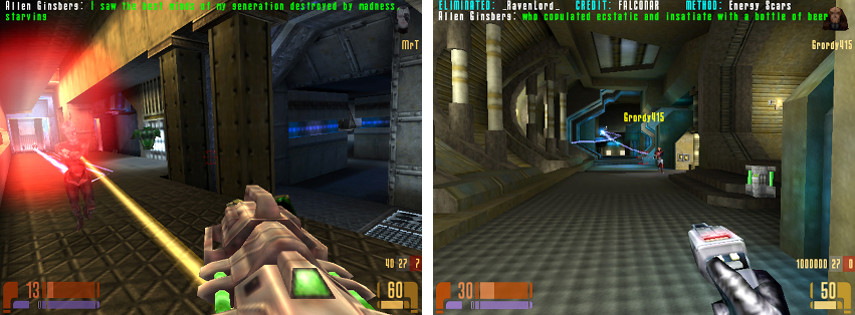

Artists in War Against Aggression – Velvet-Strike

The most famous artistic modification was a collective action by Anne-Marie Schleiner, Brody Condon and Joan Leandre, in a patch of popular first-shooter multi-player game Counter-Strike (2000) titled Velvet-Strike. Released in 2002, shortly after 9/11, the modification allows the player to spray anti-war graffiti on any wall in the game. Formulated as a critique of George W. Bush’s War against Terrorism, it calls on player community to directly involve themselves and invites others to question the ideologies of capitalism, race and gender behind the famous military strategy, reflecting the very real aggression all around us.

Building a New Civilization – Eastwood - Real Time Strategy Group Civilization Series

One characteristic of computer art creators is that they themselves don’t perceive their work as only art, or only games, but they wield these mechanisms to express themselves and create visions of different possible worlds. Eastwood - Real Time Strategy Group is one such collective, researching through games and playing with important issues of today. Their series of total modification was in the turn-base strategy video game Civilization (1991), a game universe which enables players to develop their own civilization through the ages. Eastwood’s Kristian Lukić, Vladan Joler and Zvonko Gorecan bring us a series of original gameplays developed over a decade, illuminating major power plays in global society and how they affect us. Their first patch, Civilization IV – Age of Empire was created in 2004 for the Dutch Electronic Art Festival which, alluding to another classic strategy Age of Empires, presents us with a present-day imperial battle of IT corporations dealing with new economy, different industries, surveillance, terrorism etc., instead of different countries battling for the survival of their civilization. The second part of the trilogy, the 2008 Civilization V – Age of Love, foreshadows a battle for dominance of Web 2.0 social magnates like Google and Facebook, offering players marketing techniques to win, while the latest patch from 2015, Civilization VI – Age of Warcraft, involves us in issues of cyberwar and surveillance.

Civilization VI - Age of Warcraft Gameplay by egonston

Art Performance and Video Games

In the abundant gaming world, artists have found significant inspiration for their interventions, but some of them saw these virtual spaces as a stage for their art, and its virtual inhabitants - their audience. Without the advanced technological savvy, many found online virtual worlds, MMOGs and MMORPGs like Second Life and World of Warcraft, undiscovered and unperturbed social spheres getting inquisitive about their norms and connections to the offline world. By marrying performance art with video games, artists started creating site-specific online performances, introducing art to sometimes utterly unprepared worlds.

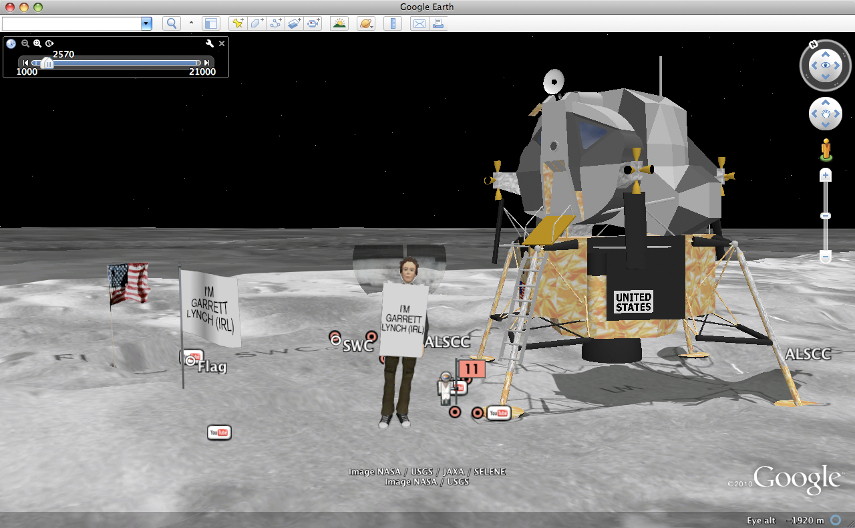

Star Trek and Poetry - Joseph Delappe’s Howl: Elite Force Voyager Online

San Francisco-born artist and Media Studies Professor from Nevada, Joseph DeLappe is considered a pioneer in online gaming performance. His 2001 project Howl: Elite Force Voyager Online was what he defines as a cyber street performance in Star Trek: Voyager – Elite Force, a first-person shooter multiplayer online game set in cult TV show Star Trek universe. DeLappe staged his work with idea of reaching an audience outside art world, but also solving the issue of isolation he felt in the Nevada desert. He entered the gamespace with an avatar named Allen Ginsberg and performed a six-hour reading of the author's celebrated beat poem Howl using the game’s chat system, putting to question the very meaning of culture in computer age.

Art and Second Life

The virtual world which attracted performers the most has always been and remains Second Life (2003). Not exactly a videogame but a Multi User Virtual Environment (MUVE), the platform provides its millions of residents a sort of virtual reality replica of everyday human life, and so presents a brand new stage for all kinds of artistic endeavors. Second Life's art world is filled with galleries, exhibitions, live concerts and theater productions, just as its offline counterpart. An interesting form of artwork, which developed in online gamespaces, is machinima, a cinematic production of real-time staged gameplays, a sort of short animated films developed in the game universe. However, it is also performance art which draws much attention in Second Life. Active performers include Annabeth Robinson, Garrett Lynch, Simon Goldin and Jakob Senneby, Gleman Jun and Second Front. These men and women explore the relation between real and virtual, agency of virtual identities and potency of online communities.

Aren’t Video Games Already Art?

As we have seen, video game art disturbs the already eroded borders of contemporary art, making it hard to differentiate between game, artwork, activism and everyday life in our more and more technologically oriented reality. But aren’t video games already art? These grand production pieces, paralleled only by the great movie industry, gave us phenomenal visual design in Final Fantasy, singular landscapes and cityscapes of the BioShock series and many others. Game art prints of such works are sold and sought after around the world, responding to a demanding new generation of audience. Also, narrative and character development is reaching higher levels every year, providing interactive storytelling opportunities literature never could. The problem is that while video game art pieces are in most cases created and presented within the world of art and its institutions, video games still largely persist in their reputation of lowly entertainment. While grand video game productions are often limited by industry requirements, artist who is experimenting with game design remains free to respond to social appetite of contemporary art and explore the workings of new technology. Yet we remain convinced that it won’t be long until we openly celebrate the wealth of this creative wonder.

Editors’ Tip: Works of Game: On the Aesthetics of Games and Art

In his book,Works of Game: On the Aesthetics of Games and Art, John Sharp describes three communities of practice and offers case studies for each. Game Art, which includes such creatives as Julian Oliver, Cory Arcangel, and JODI (Joan Heemskerk and Dirk Paesmans) treats videogames as a form of pop culture from which can be borrowed subject matter, tools, and processes. Artgames, created by gamemakers including Jason Rohrer, Brenda Romero, and Jonathan Blow, explore territory usually occupied by poetry, painting, literature, or film. Finally, Artists' Games - with artists including Blast Theory, Mary Flanagan, and the collaboration of Nathalie Pozzi and Eric Zimmerman - represents a more synthetic conception of games as an artistic medium. The work of these gamemakers, Sharp suggests, shows that it is possible to create game-based artworks that satisfy the aesthetic and critical values of both the contemporary art and game communities.

References:

- Sharp, J., Works of Game: On Aesthetics of Games and Art, The MIT Press, 2015

- Paul, C., Digital Art, Thames & Hudson, 2008

- Greene, R.,Internet Art, Thames & Hudson, 2004

- Brittanti, M, Quaranta, D., Gamescenes: Art in the Age of Videogames, Mailand, 2006

Featured images: Super Mario Bros, photo by Matt Ley, Brody Condon - Adam Killer, 2000-2002, photo via theinfluencers.org, Eva and Franco Mattes - Colorless, Odorless and Tasteless, 2011, photo via 0100101110101101.org, Ian Bogost - Cow Clicker, 2010, photo via polygon.com, Thomson & Craighead - Trigger Happy, 1998, photo via birminghammuseums.org.uk. All images used for illustrative purposes only.

Can We Help?

Have a question or a technical issue? Want to learn more about our services to art dealers? Let us know and you'll hear from us within the next 24 hours.