Until about nine months ago, leaving the European Union was not something that sensible British politicians talked about. They hadn’t, really, since the country entered the bloc in 1973, the year that Theresa May sat her O-levels. In the intervening 43 years, as the EEC became the EU; and Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair came and went; and the Channel Tunnel was dug; and the borders spread to the east; and the euro was launched, and then foundered; our relationship with Brussels seemed, more or less, to embody a settled ambivalence towards the European continent that most British people instinctively recognised as their own. Close, but separate. In, but not integrated. Related, but not the same. We did not learn French.

And then 17 million people voted to leave. Everyone has their own explanation for why. Not all of them make sense. I found out the other day that my wife’s uncle voted for Brexit because his son is training to be a doctor, and doesn’t like Jeremy Hunt, who campaigned for remain. Victory, as they say, has many fathers. Since 23 June, a great many things have been blamed – or thanked, depending on your view – for convincing the population that staying within the European Union was hurting us. Their names are more than familiar now. Nigel Farage. Globalisation. The rightwing press. The left behind. Professional politicians. Absent politicians. The financial crisis. Boris. Migrants. Project Fear. Sunderland. In their own way, and over time, these things helped create the feeling that we were trapped in something so defective, so inimical to our interests, that our best hope was to climb through a high window, and out.

But you don’t get to Brexit without someone dreaming up the window – the remedy of leaving – in the first place. And during those long years inside the European project, that was the work of the right wing of the Conservative party. To be specific, a small, somewhat esoteric part of that wing: a flash of feathers, almost, a sect of true Eurosceptic believers who dreamed and schemed for this moment for the last 25 years. Most worked for little else, with no reward, and with no sign that they would ever prevail. “Like the monks on Iona,” as one of their former parliamentary researchers told me, “illuminating their manuscripts and waiting for the Dark Ages to come to an end.”

And no one in that group worked with more devotion than Daniel Hannan, a Conservative member of the European parliament for south-east England. Hannan, who is 45, is by no ordinary measure a front-rank British politician. He has never been an MP, or a minister, or a mayor. Instead, since the age of 19, he has fought for what he calls British independence – fomenting, protesting, strategising, undermining, writing books, writing speeches and then delivering them without notes. For the last 17 years, Hannan, a spry, fastidious figure, who likes to read Shakespeare once a week, has done this mainly from the other side of the English Channel. He knows what it is to toil for a lost cause. “Here I am, Ishmael,” he told me recently, in his office at the European parliament in Strasbourg, invoking the Old Testament as he gestured around him. “Every man’s hand is against me.”

Hannan may have contributed more to the ideas, arguments and tactics of Euroscepticism than any other individual. It was Hannan, in 2012, who asked Matthew Elliott, the founder of the Taxpayers’ Alliance, to set up the embryonic campaign group that later became Vote Leave. Elliott, who is 38, describes Hannan as the pamphleteer who made Brexit seem like a reasonable proposition for millions of people. “I can’t think of anybody who has done more on this,” he told me. Others laboured too, of course, and Elliott cited veteran Tory MPs Bill Cash and John Redwood, who spent decades attacking the constitutional and economic aspects of the EU – “but Dan is the only person who has successfully created a whole worldview,” he said. “And also then done better than anyone else to be the propagandist for it.”

Hannan’s signature case against EU membership is an upbeat argument of direct democracy and free-market capitalism. He sidesteps questions about the inevitable trade-offs of leaving by insisting there will be none. Elliott was an intern when he first heard Hannan speak in Westminster almost 20 years ago. Douglas Carswell, the Ukip MP, was convinced by Hannan that Britain should pull out, in the autumn of 1993. “When I heard Boris Johnson and all those others making those brilliant points they made,” Carswell told me recently, “I thought, ‘Compare it to making a film: these guys on the silver screen are brilliant. But the script is written by Hannan, and this is largely a Hannan production.’” Theresa Villiers, the former Northern Ireland secretary, who helped persuade David Cameron to allow his cabinet to campaign freely during the vote, was “radicalised”, in her phrase, by Hannan during her time as an MEP. “On the morning of 24 June, I texted Dan congratulating him on changing the course of European history.”

And yet, Hannan is not a household name. He didn’t break out during the campaign. Fellow Brexiteers told me there were prosaic reasons for this. “The broadcasters had their own hierarchy for their own reasons,” said Michael Gove. “They took the view that some people were box-office and some people weren’t.” Besides, to allies and enemies alike, Hannan’s role has never been on centre stage. Trying to characterise his contribution to Brexit, many people I spoke to likened him to dogmatic intellectuals from the past who came first and prepared the way. Admirers mentioned Patrick Henry and Tom Paine, whose writings catalysed the American Revolution. Opponents compared Hannan to Trotsky. “You have got to have hard arses,” the Marquess of Salisbury, a long-term Eurosceptic and Hannan supporter, told me, “who are morally courageous, who consistently make the arguments, who don’t mind being unfashionable.”

The other explanation, however, is that in the climactic moment – when Brexit was put to the people – it wasn’t Hannan and his debating points that carried Britain out of the European Union, but a smaller, darker, set of instincts altogether. The final weeks of the Vote Leave campaign, with its focus on immigration and posters about Turkey joining the EU, were like nothing out of a sonorous Hannan speech. (His own 217-page book, Why Vote Leave, contains a single sentence on immigration, and Hannan supports Turkish membership of the bloc, in principle.) In the eyes of Ukip, the narrow, Hannanite case for Brexit – mostly about deregulation and sovereignty – was a sideshow next to the real event: a chorus of economic and cultural discontent. “In his own way, he is an idiot savant,” said Gawain Towler, Nigel Farage’s spokesman. “So locked up in his world that he can’t see what is on the end of his well-formed aquiline nose.”

Hannan himself is almost impossible to pin down on these questions. He is agile and skilful when he talks – like a star witness with absolutely nothing to hide – and during several conversations this summer, he showed no anxiety at all about the manner of Britain’s decision to leave the EU, or the scale of the diplomatic and economic challenges facing the country. Whenever he could, Hannan would muse on the fair-mindedness and natural intelligence of the British people, and spar with the ideas of his many opponents. “If you’re told that ‘Brexit was all about immigration,’ you can be almost certain that you’re talking to a Remain voter,” ran a sample, recent tweet.

For the rest of us, the patience and ruthlessness of the long-term leavers – a tiny band, fiddling at the political margins for a quarter of a century – will always be a breathtaking thing. “It’s revenge of the nerd,” one current cabinet minister, who voted remain, told me. “I was in awe of it.” But he observed that in all the years of plotting, there had been scant planning for the part that comes next, and no guarantee the agitation will now stop. “None of these people are builders, they are destroyers,” the minister said. “They are frightening people. They are like arsonists.” If Hannan has ever felt a moment of fear, or doubt, about his life’s work, you suspect that he will never admit it, even to himself. His term as an MEP runs out in 2019, and he plans to leave politics after that – the work of a singular, premeditated career complete. “Mission accomplie,” Hannan quipped to me, on two separate occasions. “As we like to say in Brussels.”

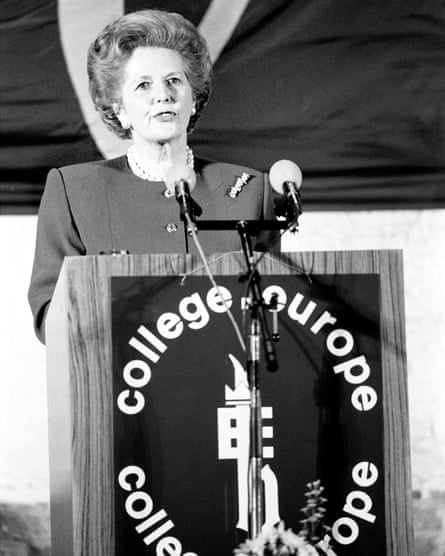

Once Britain became part of the European Economic Community, the idea of leaving it went away. A few old-stagers from the 1975 referendum on membership fought on – isolated high Tories and leftwingers, like soldiers left behind in the woods – but the cause was dead. The European project meant cheaper prices in the shops, and its force was unarguable. That began to change in the twilight of the cold war. In 1988, from the great medieval Belfry of Bruges, Margaret Thatcher decried a European superstate on the horizon, with a character and goals that were different from her own. “We have not successfully rolled back the frontiers of the state in Britain, only to see them re-imposed at a European level,” she said. The “Bruges speech” established a new form of Euroscepticism. It saw a parallel between the disintegrating, clapped-out USSR and the folly of a new federal entity, designed in Brussels. It loved America, and Nato. It wanted a world of liberal nation states. Thatcher was in office to see the Berlin Wall come down. But then, like a confusing, bad dream for her most loyal supporters, she fell, and the Maastricht treaty materialised, with its portents of the euro, political integration and everything that she had warned against.

Hannan was part of a particular generation of young Conservatives deeply marked by these events. He was in his first term at Oxford, studying history at Oriel, when Thatcher resigned on 23 November 1990. Twenty-three days later, John Major approved an early draft of Maastricht. The sense of a mighty mistake being made has never left Hannan. By the end of term, he had founded a university society, the Oxford Campaign for an Independent Britain, at the Queen’s Lane cafe on Oxford High Street.

“I remember swearing what the old adventure stories would call a terrible oath to do something,” he told me. Hannan had spent the summer travelling through the fragmenting societies of communist eastern Europe. He had seen crowds demanding the return of national borders, languages and flags. His CIB co-founders were another history student, called James Ross, who is now a composer, and Mark Reckless, the former Conservative and then Ukip MP. Hannan and Reckless had been to Marlborough College, in Wiltshire, together. They bumped into each other that summer in Budapest.

The CIB came to dominate conservative student politics at Oxford at a time of acute ideological anxiety. Nicky Griffiths, later Morgan, the former education secretary, was a member. “There were all these countries and societies and economies up for grabs,” she said. Most students were all over the place, figuring out what they believed in, but not Hannan. “He was clearly the leader,” said Mark Littlewood, the current director of the Institute of Economic Affairs, the free-market thinktank. Littlewood was pro-Maastricht and frequently found himself up against the dapper star of the CIB in debates at the Oxford Union. “Nightmare,” he told me. Handkerchief in his top pocket, Hannan wiped the floor with all comers, despite having a slightly odd, otherworldly quality. “I mean this in the fondest possible way,” said Littlewood, “you could almost think, this is someone from a slightly previous age.”

He was, in a way. The only child of ageing parents, Hannan was born in Lima, Peru in 1971. He was raised on a poultry farm outside Chaclacayo, not far from the capital. The Hannans, who had come from Lancashire to Latin America after the first world war, were part of a once-prosperous British expat community in the country. But the nation of Hannan’s childhood was destabilised by coups and anticolonial feeling. One of his early memories is of his father, Hugh, frail with illness, facing down a mob who had come to seize the estate.

Hannan boarded in the Cotswolds from the age of eight. Britain in 1979 was a revelation. “I couldn’t understand these adults saying England is finished, going to the dogs,” he said. “No one in Peru spoke like that.” Ever since, friends and foes have remarked on the power of Hannan’s learnt patriotism. Roger Scruton, the conservative writer and philosopher, first met Hannan when he gave a seminar to sixth-formers at Marlborough. “The expat mentality is belonging to the old country,” Scruton told me, “and the inability to accept that it is changed beyond repair.”

At Oxford, Hannan’s screeds on Maastricht quoted Aristotle, Shakespeare and William Pitt the Younger. But he also had an eye for a stunt. Conservative ministers visiting the CIB were ambushed and photographed with anti-EU T-shirts, while Hannan’s speeches – as his writings are now – were littered with arch, aphoristic observations. Lord Salisbury was able to run the British empire with 52 civil servants. King’s College, Cambridge, has produced more Nobel prize winners than France. The world’s oldest parliaments all hail from small islands. Goldman Sachs wants you to vote remain. “A Hannan soundbite does stick with you,” said Littlewood. “He does make you think.”

The Eurosceptic heroes of the time were the 22 Conservative MPs who rebelled against the Maastricht bill in May 1992, almost bringing down the government. The following spring, as he was about to graduate, Hannan wrote to them and offered himself as their researcher. Around a dozen agreed to form the European Research Group (ERG), with Hannan as its secretary.

In Westminster, the ERG was part of a lattice of energetic, new anti-EU organisations, such as Patrick Robertson’s Bruges Group, and Bill Cash’s European Foundation. Hannan joined the young activists who staffed the offices and wrote the pamphlets. He and Reckless, who was then working as an economist at SG Warburg investment bank, shared a flat above the John Snow pub in Soho. They hung a huge Union Jack over the fire escape, threw parties and believed they were on to something much bigger and more alive than keeping a fading government in power. “Don’t ever make the mistake of thinking Dan was a young fogey,” said Douglas Carswell, who met Hannan while he was on work experience in the Commons that year. “This was a radicalised streak of thinking.”

The job of the ERG was to keep the European debate alive, and to make contact with like-minded campaigners across the continent. But Hannan and his group also consciously sought to bend the Conservative party to their thinking. “For us the EU was the litmus test for the generation above us,” Reckless told me. After the defeat to Labour in 1997, they attached themselves to Michael Howard as the most Eurosceptic candidate to lead the Conservatives. Gove, who was writing for the Times, remembers meeting Hannan, who was supplying lines and jokes for Howard to use in the House of Commons, that summer. “He was very, very clear-minded and clear-sighted,” Gove told me. “Some people find certainty attractive. Other people find it unsettling.” Hannan was 24 years old.

For all its fervour, though, Euroscepticism in the late 1990s could not have been more unfashionable. New Labour was ascendant, and openly intent on deeper integration with the EU. In the summer of 1998, Tony Blair praised the incoming single currency and the prospect of Britain adopting the euro became the next line of battle in the European debate. The ERG published a paper, The Euro: bad for business, written by Reckless, and Hannan organised two conferences on the subject before helping to establish Business for Sterling, a single-issue pressure group to fight what was, at the time, a widely expected referendum.

Largely forgotten now, Business for Sterling set the template, and included some of the key personnel, for the 2016 leave campaign. (Vote Leave’s initial vehicle, Business for Britain, was named in homage.) Although the group was chaired by Tory rebels and right-leaning grandees – led by Rodney Leach, a merchant banker, who later became a lord; Rupert Hambro, of Hambros Bank, and the Marquess of Salisbury – it was outwardly cross-party and apolitical. “Business for Sterling were the first campaign to sort of bring those concerns out of the political margins and into the real mainstream,” Theresa Villiers told me.

Nick Herbert, who had run the Countryside Alliance, was in charge. (This year, Herbert, who is now an MP, led the Conservative campaign for remain.) He hired a brilliant young campaign director, a former investment analyst, whose last job had been in Russia, called Dominic Cummings. Hannan was by now flitting back and forth between the ERG and his job writing leaders for the Daily Telegraph. He thought about how to frame the European question for a national audience. “This was when I started realising how much the mechanics of a campaign matter,” he told me. “Simply by talking about keeping the pound rather than opposing the euro, we added 15 points.”

Business for Sterling recruited Bob Geldof, Vic Reeves and thousands of students to its cause. It helped keep opinion polls set against joining the Euro and deterred the new Labour government, and its pro-European allies in the City, at their moment of peak of popular influence. Hannan and Cummings and the rest of the new crowd – all in their 20s – came away with their first victory scars against the establishment. “We did feel that bonding that comes from a ridiculed minority,” said Hannan.

Eighteen years later, many of Business for Sterling’s funders and supporters gathered to the flag again. Villiers was one of many long-term Eurosceptic campaigners who realised that, although they were underdogs, they had fought a version of this battle before. “It is funny,” she told me. “Almost at every point I assumed remain would win. But it certainly did occur to me the disadvantage they had was they had been thinking about this referendum for possibly a year. Whereas people like Dan, it has been their life’s work. The whole of their adult working life had been building to this moment.”

Business for Sterling succeeded because it found language and symbols – the Queen’s head on a fiver – that touched the nerves of millions of people. Pulling out of the EU was a different ball game. There was no word for Brexit in the 1990s. Even Eurosceptic MPs didn’t mention it as an option. The language of choice for Tory rebels was of “reform”; “fundamental reform” if they were feeling brave. “Whatever weasel words,” Reckless told me. “Dan and I were always clear that our objective was leaving the EU, and that was what we were working towards.”

Hannan was one of the first elected British politicians to suggest the idea publicly. In the spring of 1998, believing a referendum on the euro was imminent, he began to look for a seat in the European parliament. Tory MEPs were among the most ardent pro-Europeans in the party, and it seemed like a logical, if audacious, place to take the fight. Hannan’s age – he was now 26 – and his polished, bracing stump speech marked him out from the other candidates. “I was saying we should take powers back and we shouldn’t be afraid to come out if we can’t,” he told me.

Conservative party activists loved it, but Hannan’s bold language alarmed party headquarters. “I was told that he was a fanatic,” said Edward McMillan-Scott, the leader of the Tory bloc of MEPs at the time. McMillan-Scott tried to sabotage Hannan’s campaign, and the young candidate was questioned furiously at an open primary at the London Arena in May. But the ploy backfired. Hannan delighted the crowd again, and the following summer, he was elected to the European parliament as a Conservative candidate for the south-east.

Once inside the heart of the EU, Hannan set about discrediting it. A former researcher in his office told me that duties were divided between responding to constituents and “the more naughty stuff” of seeking out waste and hypocrisy in Brussels for Hannan’s column in the Sunday Telegraph. Hannan fell out with most of his Conservative party colleagues when he wrote about the expenses they were able to claim, but he did not relent. “I was building a campaign to delegitimise the institution,” he said. In the plenary chamber, Hannan used his allotted speaking time to rail against the statist, Bonapartist European project. Fellow MEPs, particularly from abroad, listened to Hannan’s ornate rhetoric in bewilderment and dismay. “The Spanish, we don’t have these imperial dreams to go back to. We are realistic,” Antonio López-Istúriz White, an MEP from Spain’s conservative Partido Popular, told me. “There is something in his life that probably affected him.”

From day one in Brussels, Hannan also sought to bring the Tories out of their moderate grouping, the European People’s party, or EPP, and to ally them with more critical, anti-EU voices in the European parliament. Since 1979, the party had sat alongside fellow centre-right parties from countries such as Germany and Spain. But hardline Eurosceptics believed that this meant that Tory MEPs absorbed the meeker, pro-European tendencies of their continental colleagues. At first Hannan simply sat alone. But after six years of hectoring and arguing, and as new, Eurosceptic Conservative candidates were elected, he moved the entire bloc to his position. In 2005, Hannan extracted a promise from David Cameron – then a leadership contender – that the Tories would leave the EPP. In 2009, they did. (McMillan-Scott was driven out of the party.)

Concentrating on arcane goals such as breaking up the EPP was a telltale move of the hardcore Eurosceptics. Another inch gained. Another bolt loosened. “Our goal in politics should not be to get the right people in,” Hannan told me once, paraphrasing Milton Friedman, the American free-market economist. “It should be to set the incentives so that even the wrong people will do the right things.” But behaving like this, and working to another order of events, separated Hannan and the other Maastricht diehards – even from fellow Tories who might otherwise agree with them. “The view at the centre was these were the people who had kept the Conservative party out of power for years,” said Gove. “Whatever they are most passionately in favour of must perforce be at best eccentric, at worst electoral disaster.”

One new MP in 2005 remembered being lobbied to support the move out of the EPP and asking an older colleague for advice. “He said, ‘You just cannot. It looks good. But you cannot give an inch to these guys because they will never, ever accept it. They will take and take and take until they have won.’” Several Conservative MPs I spoke to for this article compared Hannan and his set to “entryists” and “Trots” for their ideological purity, their quest to reassert what they regard as Britain’s lost place in the world. “They are grammar-school imperialists,” one MP told me. “A hundred years ago Hannan and his ilk would have been able to vent their rather bizarre beliefs bullying people in a nether-province of India.”

Hannan says such insults have never bothered him. “It passes by as the idle wind that I respect not,” he said. He simply regards himself as a different kind of a politician. “I think public life for me has a slightly didactic role, OK,” he said. “You should be trying to shift the centre ground of public opinion.” Since becoming an MEP, Hannan has written six books, from polemics, such as The New Road to Serfdom, a critique of America’s “European” drift under President Obama; to historical homilies such as How We Invented Freedom & Why It Matters, a 400-page exploration of the genius of English liberty, tracing its origins back to Anglo-Saxon witans and the Magna Carta.

Operating apart, however, means that Hannan can sound alarmingly unlike most other British politicians. How We Invented Freedom includes a long extract from a speech made by Enoch Powell on St George’s Day, 1961. Another devout Eurosceptic, Powell eulogised the English language that day as “tuned already to songs that haunt the hearer like the sadness of spring”. The one-time health minister is now remembered for his “rivers of blood” speech of 1968, but Hannan frequently cites Powell as the model of the opinion-forming politician he would like to be, describing him, when we spoke, as the “supreme exemplar of that in his generation”.

For years, within the Tory party, Hannan was also notorious for helping to write William Hague’s so-called “foreign land” speech in 2001. The speech’s attacks on Europe and tough line on asylum seekers were perceived as racist, and it is still regarded as a nadir in the party’s recent political messaging. But when we talked about the speech this summer, Hannan said: “There is sort of a hobbit-like element to a lot of British people. They don’t want to be told something until they have worked it out for themselves.”

Still, there were times when the road seemed so long, and so hard, that Hannan despaired. In 2005, the EU seemed to defy referendums in both France and the Netherlands, where voters rejected a new constitution for the bloc, by repackaging the proposed reforms and forcing them through under a new name: the Lisbon treaty. Hannan wondered whether the whole project was in fact unstoppable. “They’ll do it all by stealth,” he thought, “and they will get to where they want to go.” Cameron’s new-look party was determined “to stop banging on about Europe” and Hannan came close to joining Ukip. In 2007 and 2008, he met Farage several times to discuss his defection, but in the end, the Tories broke with the EPP, and he stayed with the Tories.

In November 2009, though, the Conservatives abandoned their own manifesto promise to hold a referendum on the Lisbon treaty. Hannan called Cameron’s office to resign from his duties in Brussels – he was the party’s legal affairs spokesman in Europe. A senior aide picked up the phone. “I said … I just think you’ve made the most terrible mistake,” Hannan recalled. But he promised to step down without publicity. The adviser thanked him, and asked Hannan what he planned to do next. “I’m going to devote myself full time to securing and then winning a referendum on leaving the EU,” Hannan replied. The aide laughed down the line. “Good luck with that.”

Hannan put the phone down. He was in his office in Brussels. The Macauley poem, Horatius at the Bridge, entered his mind: “Who will stand on either hand / And keep the bridge with me?” He thought of Carswell and Reckless, his closest friends in politics, whom he spoke to almost every day. (Reckless became a Conservative MP a few months later.) Then Hannan ran through his old, Eurosceptic allies. He ended up in touch with the Democracy Movement, a descendant of James Goldsmith’s Referendum party, which had entered candidates in the 1997 election. At the time, the Democracy Movement had its own plan to bring about an in-out referendum in the UK, which was called the People’s Pledge.

Like other successful Eurosceptic campaigns, the People’s Pledge was scrupulously cross-party – it had mainly Labour staffers – and didn’t make the mistake of asking for too much. The premise was simple: it identified Labour and Conservative MPs under pressure from Ukip in their constituencies, and asked them to publicly support a referendum on the EU. The People’s Pledge launched in March 2011. By October, there was a petition signed by 100,000 people, a debate in parliament and 81 MPs signed up, more and less against their will. Hannan spoke at rallies and impressed donors.

Europe was the last thing that the Conservative-led coalition government wanted to address. There was so much else to attend to. The economy. Public service reform. The big society. “Oh God, so annoying,” is how a former Cameron adviser described the pressure from the Eurosceptics. “Constantly demanding to see the prime minister.” Gove, then education secretary, felt particularly torn whenever the subject came up. The tactics of the People’s Pledge, and Hannan’s role in it, made many of his colleagues uneasy. On the substance of the argument, however, Gove sided with the young speechwriter he had met in the 1990s. “More and more of what Dan said, I would find myself agreeing with,” he said. “At the same time, I tried not to think about it whenever possible.”

With the eurozone in crisis, and signs of support for a referendum from Labour, the pressure grew. In March 2012, Boris Johnson signed the People’s Pledge. Six months later, a rebellion masterminded by Reckless defeated the government over its contribution to the EU budget. Cameron was cornered, and announced the planned referendum at Bloomberg’s London headquarters the following January. Like George Osborne, Gove argued against it. “I didn’t think offering the referendum was a good idea,” he told me. “I thought, This is being offered as a stopgap, not as a carefully considered recalibration of Britain’s relationship with Europe. It is more about dealing with an immediate political dilemma.”

By then, the skeleton of the leave campaign was already in place. In August 2012, Elliott and Hannan had been invited to spend the weekend at the country house of Lord Leach – the former chair of Business for Sterling, who died 11 days before the referendum – on the Norfolk coast. Over the years, Leach had become more or less neutral on the EU question, and he had arranged a house party to discuss possible options for a referendum. Of the group, Hannan and Elliott were the most doubtful of Cameron’s ability to reform the EU.

“Dan was basically, ‘He is not going to do it. Don’t believe him,” Elliott recalled. In the garden, Hannan urged Elliott to start thinking about what a Brexit campaign might look like. A year earlier, Elliott had run the winning “no” side of the referendum on the alternative vote with a message that had impressed Hannan with its bloodymindedness. Rather than engaging with the principles at stake, Elliott had focused on the cost of changing the voting system – an impressive-sounding £250m – and sent dustbin trucks apparently heaped with money through the streets of Westminster.

“I thought it was the most rubbish argument ever,” Hannan said. But it worked. Behind in the polls at the start, “No to A/V” won with 67% of the vote. Elliott had also proved adept at bringing rightwing donors and thinkers to what was a dry, democratic exercise. Leach had chaired the campaign. While Crispin Odey, a hedge fund manager who later contributed more than £650,000 to pro-leave groups, chipped in £20,000. (In the run up to the vote, Odey bought gold and bet against house-building companies. On 24 June, as the pound collapsed, he made around £220m. “Crispin,” as a friend told me, “has the common touch of a Medici.”)

The new campaign took its playbook from Business for Sterling. Elliott used the initial vehicle, Business for Britain, to set about winning friends and funding from the City. At the same time, he pondered the looming, awkward alliance with Ukip and more protectionist, anti-immigrant strains of anti-EU thinking. “We needed each other,” he told me. Based on the 2014 European election results, Elliott reckoned that the Ukip vote would be worth around 30% in the referendum. The job of Vote Leave would be to win the centre ground with a reassuring, forward-looking tone.

Elliott compared the task to the New Labour project of the 1990s. “We needed new characters, like Gove and Boris and Gisela Stuart,” he said, “and a new message. Dan in a sense provided us with that message.” Elliott hired Cummings, as campaign director, who coined the all-important slogan, “Take Back Control”, while the deliberately crude figure of £350m per week, to describe Britain’s EU budget contribution, echoed Elliott’s successful A/V strategy.

Hannan worked the political side. In the autumn of 2014, his allies Carswell and Reckless left the Tory backbenches for Ukip – one month apart – in synchronised defections designed to keep up the pressure on Cameron for a referendum, and, in theory anyway, dilute Nigel Farage’s dominance of the party. A year later, as the vote approached, and Cameron began his doomed renegotiation, Hannan reached out to Gove, Johnson, Villiers and others. “I spoke to Boris and made my pitch,” Hannan said. “The only thing I will say is that he was obviously agonising about the issues.” (Johnson did not respond to a request to comment for this article.)

By the time the actual campaign was under way, Hannan’s work was more or less done. “Twenty years of inch-by-inch, person-by-person, converting those in the Conservative party to his vision,” said Littlewood, of the Institute of Economic Affairs. Hannan went to Vote Leave’s weekly strategy meeting, chaired by Gove, but his biggest impact on the national debate was probably subliminal. “Dan would often express views that I had myself,” said Gove, “which he would present in a crisper, more elegant and more coherent way.” At least three of Gove’s more memorable soundbites – about people being fed up with experts, joking about British MEPs losing their jobs, and comparing pro-remain economists to Nazi scientists – were Hannan lines. Villiers borrowed freely from her friend’s speeches. From needling and courting one or two “outers” in the late 1990s, Hannan watched 137 Conservative MPs announce their support for Brexit.

He took part in 104 events and debates during the campaign, giving his final speech at Runnymede, where Magna Carta was agreed in 1215. He spent the night of the vote in Vote Leave’s headquarters, next door to Lambeth Palace, with Cummings and the rest of the team. (Elliott was in Birmingham.) There was no party planned. “Dominic is very puritan about these things,” said Hannan. When victory was certain, Hannan stood on a desk in the office and delivered the St Crispin’s Day speech from Henry V – “We few, we happy few, we band of brothers” – substituting the names of people who had worked on the campaign. He didn’t go to bed until midnight the following day.

On the Monday after the vote, at around six o’clock in the evening, Matthew Parris, the conservative columnist, found himself standing a few feet away from Hannan on College Green, outside the Houses of Parliament. Hannan was having an argument, on air, with Christiane Amanpour of CNN. When the fall of Cameron consumed other senior figures from Vote Leave, Hannan became uneasy about the way that Brexit was being reported, particularly abroad. “The story taking shape was that Britain had just voted, as it were, for Donald Trump,” he told me. Hannan took on as many interviews as he could, to put across a more positive interpretation of events, but he often found himself under hostile questioning. With Amanpour, he lost his temper. “You guys have been shouting ‘racist’ for so long,” he told CNN, “that you weren’t listening to what we were actually saying.”

Even by the standards of those numbing, chaotic days, Parris was taken aback by the ferocity of the encounter. “He was very uncomfortable and very angry,” Parris told me. He has known Hannan since the mid-1990s, and later accused him in the Spectator of being willing to exploit xenophobia in order to pursue his own, more abstract goals. “He has ridden a tiger, and knows the tiger he rides,” Parris wrote. “I find him a bit scary,” he said, when we spoke. “I don’t think he sees himself in politics to give effect to what the public thinks, but to what the public ought to think, which is quite different.”

Hannan, naturally, cannot bear this kind of talk. When we first met, in Strasbourg, in early July, I asked him whether he really believed that the nation had voted for his free-market, internationalist version of Brexit. “Can you see how patronising that is?” he replied. “I mean, remainers are saying basically, ‘These thicko, working-class bigots weren’t listening to you. And let me now tell you – having ignored them – let me tell you what they really think.’”

Instead, Hannan spoke of polls that showed that sovereignty was the primary concern of leave voters, rather than immigration, and of the economic shock that had not come. He admitted that because of the closeness of the vote, we were unlikely to become the “offshore, low-tax, global free-trading entrepôt” that he longs us to be. Hannan’s chosen Brexit would be rather soft, by current standards: something along Swiss lines, with opt-ins for various sectors to the regulations of the single market. He believes that compromise on free movement is possible, and that the Swiss government was making progress on the subject until talks were shut down before the British referendum. There is precedent, he pointed out, in his Hannanite way: EU immigration to Liechtenstein is capped at 71 people per year.

It all sounded so reasonable when he talked which, of course, is Hannan’s gift. “Even if you fundamentally disagree with him, you find yourself nodding along,” said Nicky Morgan. Like other senior politicians who campaigned for remain, she disagrees with Hannan’s analysis of what drove the result, and is anxious about the future. “I think we are in the calm before the storm,” she said. Morgan has been called a traitor twice in her constituency of Loughborough, and has heard calls for the removal of a Polish community that has been there since the second world war. She didn’t hear much about free trade and parliamentary supremacy in May and June. “Talking to people who voted leave … ‘back’ was a very important word. One of the most depressing things was this, ‘I want to take our country back.’ Back to what?”

Nigel Farage has his own reasons for disagreeing with Hannan. The two have not spoken since 2014. (Farage says the two fell out over his approach to immigration; Hannan says that Farage underwent “a personality change”.) We met recently, in Westminster. The celebratory moustache was gone. He was just back from the US, where he had addressed a Trump rally in Mississippi, and was smoking on the patio. He had been thinking about the similarities between the core Brexit vote, and Trump’s supporters. “It’s not the have-nothings … They have got something, but they are concerned about the change in society,” he said. “The basic feeling is that something has gone wrong; that we are not in control; that our political class aren’t the same as us, are detached from us.”

Like Hannan, Farage started out making a case for why Britain should leave the European Union – around trade and sovereignty and democracy – in the early 1990s. But he realised that the argument only went so far. “It’s just not what most people are bothered about,” he said. The mystery, for Farage, is that Hannan and his group have never figured this out. “It’s cultural,” he said. “They seemed to approach the referendum as if it was an Oxford Union debate. I don’t think they have met any real people in their entire lives.” Farage said he didn’t hear much about Hannan’s free-market, open ideals on the doorstep either. “It is another disconnect isn’t it?”

Is it possible for someone to crave something for so long, and then be deluded about why it happened? To strive and strive, only for the country to fall into a different, meaner, poorer future? I once asked Hannan why he had dedicated his life to getting us out of the European Union. “It was the independence issue,” he replied. “It was the idea of self-government.” I told him that – as a citizen of the same country – I still didn’t really get it. I couldn’t see the freer land that he was seeking, even now that we had cut ourselves adrift. “It’s a big philosophical difference,” said Hannan. “Between the mentality of the powerful bloc run by competent, educated people and the mentality of ‘trust the people’.” He didn’t want to be rude. “We are all conditioned by outlook, experience, genes, whatever. Two people will very often look at the same thing and have very different takes on it.”

We were on a train back to London, in late August. Hannan had just spoken at a Conservative club lunch in Worthing, on the south coast, where he was the guest of honour. The lunch had been held in a small hotel. More than a hundred had turned out, a swirl of floral prints and club ties. I sat on Hannan’s table, where he remarked, thought-provokingly, on the scale of British immigration to Spain. “It is the great migration of our time,” said Hannan, pointing out that there were more British people in Spain than people of Pakistani origin in the UK. “How many of them are on benefits?”, one woman, in curls, asked promptly. Hannan ate his roast beef, smiled, and did not reply.

After lunch, he rose to speak. The Olympics had just finished, and someone gave Hannan a homemade medal for his work on Brexit. The MEP thanked the room for putting him out of a job. The microphone wasn’t working, but he did not need it. With his voice high and precisely cadenced, Hannan spoke of his hopes for the years to come. “I don’t think it’s going to be difficult,” he said. “I don’t think it’s going to be that hard.” And he exhorted the audience to remember great British achievements: the medals table, and two wars against German tyranny, the abolition of slavery. “The idea that we can’t now make a success of living under our own laws, trading with our friends and allies on every continent, while governing ourselves, is not worthy of a country like this one.” Hannan paused. “Cheer up my friends.” The lunchers laughed. Sunshine poured in. The cataclysm could not be felt. “Listen to the drone of the bees in lavender, and ask yourself where in the world would you rather be?”

Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, or sign up to the long read weekly email here