In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Robert Smithson and his partner Nancy Holt were leading figures within what became known as land art, using the raw stuff of nature in situ as a sculptural medium. In the US, their fellow travellers included Michael Heizer and Walter de Maria, whose works gouged great trenches into wild rock or solicited lightning strikes. (In Britain, the tendency translated into the comparatively gentle, perambulatory art of Richard Long and Hamish Fulton.)

There’s no escaping the chutzpah – one might even say arrogance – required to work at this scale. The masterpieces of land art – of which the most famous is Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) on Great Salt Lake in Utah – are situated in inhospitable, and, at times, inaccessible locations. This is art with a dose of extreme sports. The hazards involved were real: Smithson died in a light-aircraft crash aged only 35 while surveying the site for what would be his final earthwork, Amarillo Ramp (1973).

With works far-flung, how does one stage a Smithson show? The title for this show, Hypothetical Islands, gives a clue: while there is a single neon sculpture and early sci-fi inspired drawings, this is largely an exhibition of the artist’s unrealised projects. (There remained many such at the time of his death, though who knows whether that might have changed?)

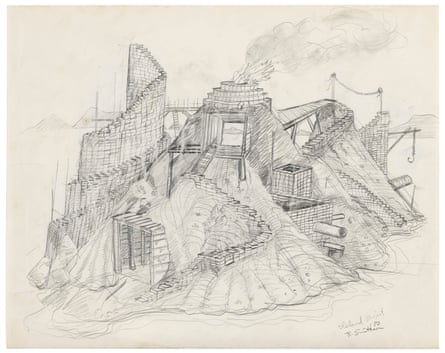

Inspired by stories of ancient Atlantis, sci-fi fantasies and rock-hunting manuals, Smithson planned a variety of sculptural islands, many of which are represented here as pencil sketches. Some schemes are elegantly serpentine, one resembles the forking branches of fallen trees, another matzo balls in soup. It’s hard to get any sense of scale, and impossible to understand the context in which Smithson was picturing the works. The site was crucial – a caption notes that Smithson and Holt acquired a remote outcrop on which to realise a specific work, only for the artists to decide that it was too picturesque to alter.

The question of beauty, and our understanding of it in the natural world, is interesting in this context. Smithson once compared claw-mouthed digger trucks to “mechanical dinosaurs stripped of their skin”. He saw the brutality involved in the production of his works, which at their greatest involved the digging, transporting, dumping and forming of vast quantities of local materials. Six thousand tons of black basalt rocks and earth went into Spiral Jetty.

Holt’s films are intrinsic to Smithson’s projects, not only bringing the earthworks into the gallery but also documenting trips to identify sites, the gathering of ideas and materials, and the long, tricky process of construction. The mood is often desolate, with the artists travelling great distances to wind up in landscapes that feel quasi-apocalyptic.

At the saline Mono Lake in California, they take turns walking along the shore, sending up thick eddies of oily black flies as they go. We are told about the living clouds of larval worms hatching at the water’s edge, feeding on algal slime. It’s presented like a cursed planet from one of Smithson’s sci-fi tales. Today, Mono Lake is protected as a rare and fragile environment. Our understanding of land requiring protection has shifted since Smithson’s time, no longer just a question of beauty but of biodiversity.

Like the earthworks themselves, Holt’s films are slow and repetitive, and the moments of realisation glorious. Swooping around Spiral Jetty, a helicopter captures the lake turning from pink to pewter in the evening light, the sculpture at last rising like a black whirlpool out of a sheet of silver-white water. The final film shows Holt with artists Tony Shafrazi and Richard Serra finishing the gruelling construction of Amarillo Ramp in Smithson’s honour after his death: it’s a moving farewell.

This is also the final show at Marian Goodman’s London gallery, a space off Golden Square in Soho, with a handsome old wooden staircase and skylit upper floor. Its ambitious programme has included a museum-scale show on animals in art, Nan Goldin’s elegiac portraits of New York’s queer bohemia, and the awesome theatrics of Tavares Strachan’s Black history world-building, In Plain Sight. Blame Brexit, and blame Covid, too – this gallery’s departure will leave a gap in the London scene.

Robert Smithson: Hypothetical Islands is at Marian Goodman Gallery, London, until 9 January.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion