This article has been slightly revised following the January 7, 2015 removal of Andres Serrano's Piss Christ from the Associate Press' website. The AP action came after Timothy Carney of The Washington Examiner pointed out the AP's double standard of continually representing a photograph offensive to fundamentalist Christians while refusing to publish the cartoons mocking the Prophet Muhammad published in the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo. The January 7, 2015 murder of Hebdo, the paper's editor Stephane Charbonnier, cartoonist Jean "Cabu" Cabut and 10 other people at the paper's Paris offices was carried out by Muslim terrorists affiliated with al-Qaeda Yemen in retaliation for the Habdo cartoons.

There is speculation the AP may also have been taking proactive steps to quell further violence in the wake of the Paris terror. Piss Christ had in 2011 brought violence upon a museum in Avignon, a mere three-hour ride from Paris. Although in that incident Piss Christ was attacked by French Catholic fundamentalists wielding hammers and sharp objects on Palm Sunday, Jesus is regarded a revered prophet in the Quran, making its apparent sacrilegious imagery a magnet for fundamentalist Muslim terror. The art work, which normally hangs in art-dealer Yvon Lambert's 18th-century mansion gallery in Avignon was on loan to the local museum at the time of the 2011 attack. The Guardian's Angelique Chrisafis wrote, "Civitas, a lobby group that says it aims to re-Christianize France, launched an online petition and mobilised other fundamentalist groups. The staunchly conservative archbishop of Vaucluse, Jean-Pierre Cattenoz, called Piss Christ "odious" and said he wanted this "trash" taken off the gallery walls. The gallery complained of "extremist harassment" by fundamentalist Christian groups who wanted the work banned in France." Below is the commentary I wrote in the wake of the Avignon attack, and which I am recalling in the week following the brutal Charlie Hebdo terror.

-- Added January 12, 2015

In 1989, the year I wrote the original version of this article, art critics were still talking and writing a good deal about "postmodernism." Among the numerous reasons we were persuaded in the 1980s to attach the prefix "post" to the modernist movements in art that had come to define twentieth-century culture in the West was the singular presumption that art's power to offend and shock had significantly diminished. No longer would we see a public scandalized by art, we thought, to the degree that it had been with the debut of Edouard Manet's 1863 painting, Le déjeuner sur l'herbe, for its depiction of two nude women seated outdoors with two fully clothed bourgeois men. Nor did we think the public would ever again be shocked as it had been by Pablo Picasso's 1907 cubist painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, with its abstract coterie of prostitutes at rest. Nor even as they had been by Marcel Duchamp's 1917 urinal audaciously exhibited without alteration or embellishment as a newly conceptualized "readymade" sculpture that the artist sardonically deigned to call Fountain.

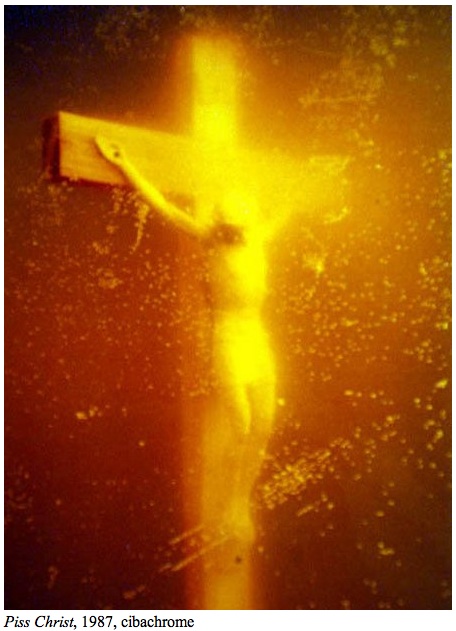

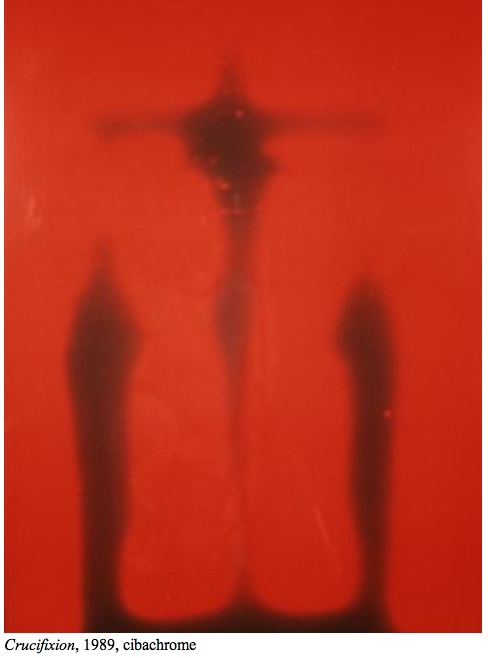

But then 1989 turned out to be the year that we art critics found ourselves to be wrong about the larger public's relationship to contemporary art. It was, after all, the year that Jesse Helms led Congress in an attack on Andres Serrano's Piss Christ, the now infamous cibachrome photograph of a crucifix submerged in urine, when it was learned that the photo had received funding from the National Endowment for the Arts. It was also the year that a traveling exhibition of photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe scheduled to be hosted by the Corcoran Museum in Washington, DC was unceremoniously cancelled for obscenity.

Twenty-two years later, conservative Americans showed themselves still to be capable of waging whole-hearted culture wars after The National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC last November removed David Wojnarowicz's 1987 video A Fire In My Belly for its depiction of a crucifix overrun by ants. Although the imagery was intended as a metaphor for what then amounted to the tens of thousands of Americans being overtaken by AIDS, as well as an ironic reminder that the Christians who opposed funding for AIDS research worshipped a Christ who had both preached charity and been foresaken, as were many AIDS victims, at the hour of his death, the first response of many viewers to the video was to see it as sacrilegious. And just this week, we are again reminded of the violent discord that art can unleash with the attack of vandals on Piss Christ in Avignon, France.

In fact, what the art world has learned in each of these instances is that, though the seasoned consumer of art is not only no longer scandalized by iconoclastic art but expects it to be transgressive, the public-at-large has pre-set limits to its tolerance of art and artists, particularly when the art they find offensive has been succored by public funds. Ironically, the recent, highly publicized controversies over censorship and sponsorship of art may have renewed the vigor of artists who seek out transgressive cultural signage to the point that the long-dormant notion of a scandalous avant-garde can and does still exist.

In light of the ongoing conflict between the cultural cognoscenti and the public-at-large, it befits a discussion on the psychically- and erotically-charged art of Andres Serrano to begin it by exorcising the cliche of art-as-scandal. In my conversations with Serrano in the 1980s, contrary to expectation, I never once heard the artist profess a desire to scandalize or alienate his audience. He certainly never foresaw that a quarter of a century after it's making Piss Christ would remain the target of repeated attacks in words and action. (The Avignon incident wasn't the first time a version of the photograph was vandalized. It was also attacked in 1997 at the National Gallery of Victoria, Australia, where gallery personnel reported having received death threats.)

No doubt we critics haven't done enough to dispel the cliché portraying artists as motivated by no more than a desire to confront and subvert the sedate values of the middle class. In Serrano's case, acting the bad boy isn't at all the motive for his eroticized art. This can be seen in both his play with erotic and political signage as much as in his play with formal and ironic compositions and subjects. And at the very heart of the series he executed in the mid-to-late 1980s, we find a measured balance of both the sublimation and de-sublimation of primal materials and psychology that is being played out in works like Piss Christ. That's sublimation, the Freudian explanation for the conversion of biological drives into the "higher," principled achievements of civilization. Freud introduced his theory of sublimation in 1908 in the famous essay, "Civilized" Sexual Morality and Modern Nervousness. Most relevant to our consideration of Piss Christ are the two paragraphs by Freud excerpted below.

Our civilization is, generally speaking, founded on the suppression of instincts. Each individual has contributed some renunciation--of his sense of dominating power, of the aggressive and vindictive tendencies of his personality. From these sources the common stock of the material and ideal wealth of civilization has been accumulated. Over and above the struggle for existence, it is chiefly family feeling, with its erotic roots, which has induced the individuals to make this renunciation. This renunciation has been a progressive one in the evolution of civilization; the single steps in it were sanctioned by religion. The modicum of instinctual satisfaction from which each one had abstained was offered to the divinity as a sacrifice; and the communal benefit thus won was declared 'holy'. The man who in consequence of his unyielding nature cannot comply with the required suppression of his instincts, becomes a criminal, an outlaw, unless his social position or striking abilities enable him to hold his own as a great man, a 'hero'.

The sexual instinct - or, more correctly, the sexual instincts, since analytic investigation teaches us that the sexual instinct consists of many single component impulses--is probably more strongly developed in man than in most of the higher animals; it is certainly more constant, since it has almost entirely overcome the periodicity belonging to it in animals. It places an extraordinary amount of energy at the disposal of 'cultural' activities; and this because of a particularly marked characteristic that it possesses, namely, the ability to displace its aim without materially losing in intensity. This ability to exchange the originally sexual aim for another which is no longer sexual but is psychically related, is called the capacity for sublimation.

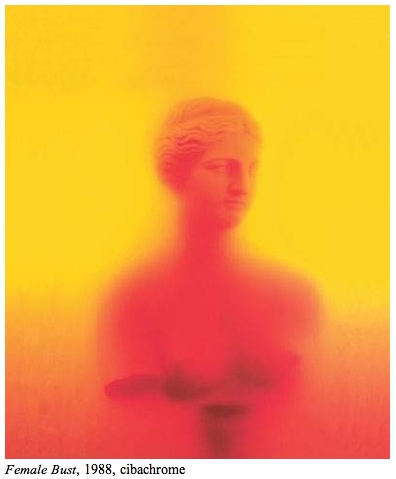

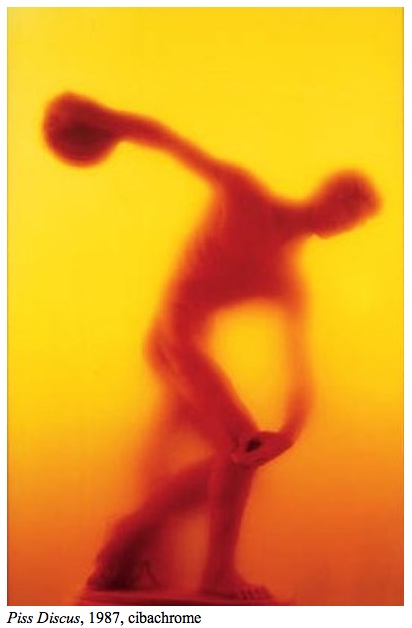

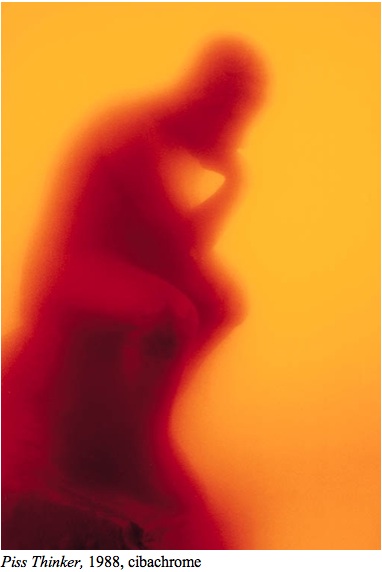

Freud's notion of sublimation, and Andres Serrano's counter-notion of de-sublimation are central to Serrano's Piss Christ and other artworks employing urine, blood, excrement, menses, and semen. For that matter, the very act of making art from these materials evokes the twin processes of sublimation and de-sublimation at work in all art. If sublimation is the displacement of libidinal desire and pleasure that we as a civilization socially convert and elevate into sanctioned behavior, status, and objects--a process that is both rudimentary to all human enculturation and concealed by it--then de-sublimation is the reversion of some artists back to an appreciation of the natural conditions of our own body that we enjoyed as infants but were interrupted by the "reality principle" of social mores--what our parents and guardians imposed as "right" and "wrong." It is artistic de-sublimations like those by Serrano that cause many in society to deem transgressive art as "aberrant," "perverted," even "criminal" when left unchecked by socialization and its morality or ethics. In Piss Christ, Serrano signifies the swing from sublimation to de-sublimation. But we know that Christianity isn't his target from viewing the same immersion into urine of such exalted cultural icons as the classical Greek bust of the Aphrodite of Cnidus, the Rodin Thinker, and the Discus Thrower of Myron. The variety of cultural signifiers submerged by Serrano suggests the crucifix is just one among many Western icons weighed against metaphors for repressed desires and drives that are wholly natural. In this sense, Serrano is simply reconciling nature with civilization. And yet, since no outrage was expressed by art aficionados over the "blaspheming" of Rodin, nor by antiquarians over the "defacement" of classical sculpture, one can assume the public outcry against Serrano's Piss Christ is strong evidence that mainstream religion in the West is a long way away from being displaced or pacified by secularism.

I repeat for the benefit of the outraged Christians among us: Serrano's pairing of iconography with bio-products isn't concerned with religious signage. The artist is aiming the camera of the mind at the most exalted achievements of civilization. Sublimation, after all is no less than the process of raising the most basic pleasures of human experience to the level of high art. In other words, the most advanced art, ideas, and systems--the qualities we associate with the status quo of civilization--are but the stuff of metamorphosis, of evolution if you prefer, from simple infantile, primitive, even animal pleasures to those requiring a high degree of skill and ingenuity. in the simplest sense, Serrano traces human pleasure from the infant's fascination with urination and defecation, to the adolescent's preoccupation with menstruation, and ejaculation, to the adult's fixation with sustenance and advancement. If this seems at all doubtful, we need only recall that Freud traced all aesthetics, economics, and sciences back to the infantile elation in excrement when he wrote on how defecation in particular provides the child with the first experience of production, creativity, and ownership.

In tracing the origins of human empathy with materiality back to infancy (and in an evolutionary sense, beyond it to animal pleasure), Serrano and other artists working with bio-products allude to what we've learned from (or at least imagined in) the annals of psychoanalysis. These records brim with examples of infants reveling in the discharge and handling of their own excrement and can be confirmed by many parents who supervise their children's toilet training. Artist John Miller has even inferred that art-making's cathectic nature (that is, the artist's proclivity to invest objects with libidinal energies traditionally suppressed by moral institutions) actually originates in this early pleasure derived from defecation and urination.

According to this classic view, as parents subsequently disapprove and prohibit a child's enjoyment of excretion and establish a regimen for its production and disposal, the child is conditioned into fusing primitive concepts of authority, production, creativity, and ownership into one psychic amalgam with shame, fear, disgust, pride, and morality. This amalgam is unconsciously associated by the child throughout life with all experiences and concepts of economy, professionalism, institutions, and class. Even the acquisition of objects and the giving of gifts conjure the complex of emotions established by infantile potty discipline (as it was believed by Freud that the child conceives of its excrement as a gift to be shared with others).

During this time, what Freud called the reality principle--the "correction" by the parents and early teachers of the child's libidinal pleasures by cultural or environmental variables--ensures that the child does not acquire or revert to "aberrant" urges and tastes unsuitable to the given social sphere. A pleasure with toys, pets, learning, and other children is thereby encouraged in the child as an alternative to (and sublimation of) the pleasure of excrement. As the child matures, this sublimation is transferred gradually from the sphere of toys to the sphere of objects coveted by adults. Thus, in traditional Western societies, money, cars, ipods and iphones, laptops, guns, real estate, masterpieces, jewelry, makeup, haute couture, the stock market, sexuality, childbearing, political office, established religion, science, technology, moonwalks, nuclear power, and ICBMs gradually come to replace - with a flourish of societal approval--the simple contentment once derived from one's own feces. In fact, Freud demonstrated in the essay "An Infantile Neurosis" how libido energies can be sublimated even to a concept of God.

De-sublimation, however, is what is conventionally thought to result when "the reality principle goes wrong;" the brain's neocortex yields to its limbic system, and the individual, guided by the pleasure principle, acquires proclivities not sanctioned by traditional societies, often even lapsing into deviant and criminal pleasures. And yet, the pleasure principle is allotted its own territory in culture--so long as it doesn't violate the ethics and aesthetics maintained by the reality principle. Should the pleasure principle ever cross the culturally sanctioned line, the reality principle swiftly drives it back.

This is clearly demonstrated in the viewer's response to art made by Serrano. When first encountering a Serrano cibachrome that refers to urine, blood, or semen, the viewer unaccustomed to contemporary art may find the work pleasurable, even beautiful, as Serrano made this particular series from the late 1980s appealing to the eye. But upon finding out that Serrano is depicting the iconography of civilization in urine, some viewers recoil from the work in disgust. This almost instantaneous reflex--this conversion of enjoyment to indignation--exemplifies the repression of the pleasure principle instilled in the viewer during infancy and continuously recalled by the reality principle for the preservation of some "higher" ethic or aesthetic. It's the naked reaction of the "civilized" viewer to the de-sublimating impulse always at work in (yet often at war with) socialized behavior.

The manner in which a viewer reacts to Serrano's realignment of signs, particularly those signs countering prevailing values, will be determined by the significance assigned the sign during its sublimation in a specific viewer's life. The vandalization of Piss Christ is an example of what happens within the individual who finds his revered cultural signs associated with biological functions and products traditionally invoking shame, disgust, lust, or anxiety. Serrano was fully aware when he made Piss Christ that he would invariably be setting off chains of emotional reaction within whole sectors of society. Just by drawing attention to somatic-erotic functions, Serrano, and other artists like him tug at the viewer's encultured, psychic reflexes and dislodge associations long repressed from consciousness.

Georges Bataille hypothesized that violent reactions to wasteful, disgusting, and lascivious contents in art are psychological re-enactments of biological ejections. In his essay, "The Use Value of D.A.F. de Sade," Bataille wrote that such contents together present a common character in that the object of the activity (excrement, shameful parts, cadavers, etc...) is found each time treated by the viewer as a foreign body and can just as well be expelled following a brutal rupture as be reabsorbed through the desire to put one's body and mind entirely in a more or less violent state of expulsion. But, with the 1980s issuing the Age of AIDS, Serrano's bio-products implicitly projected the even more menacing foreign body of HIV. With HIV being transmitted in human body products, hysteria not only encircled the AIDS patient but also trespassed into the clinic. Blood, semen, urine, and feces were no longer just indelicate or perverse when encountered in social contexts outside health care or biology. Even in 2011, with the availability of antiretroviral treatments reducing the fear surrounding AIDS, blood, semen, urine and feces remain "biohazards" to be managed cautiously.

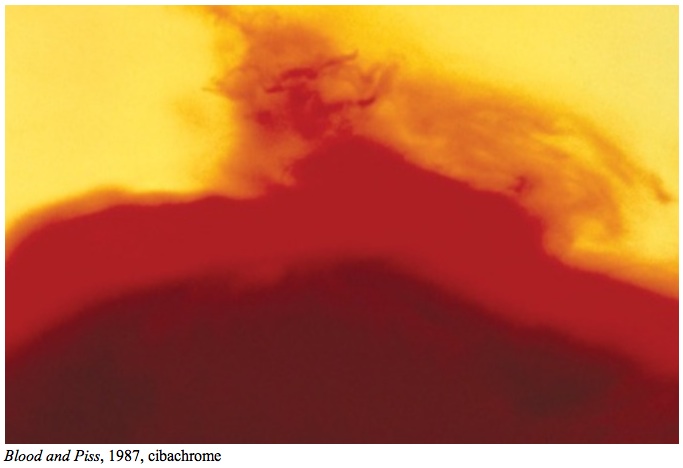

In such a socially-charged environment, Serrano can be seen as probing the social conscience responsible for impounding its failures. The artist pays particular attention to deviant or primitive sublimations and the measures taken by society to ensure their correction. At a time when a vast sector of American society began being subjected to urinalysis and bloodtests as part of its combat against drugs, AIDS, drunk-driving, terrorism, and on-the-job theft--even as controversy rages over whether or not such tests constitute an infringement of individual civil liberties protected by The Bill of Rights--Serrano, by contrast, depicted urine and blood flowing with the romantic, Whitmanesque freedom more conventional photographers savor when depicting mighty rivers. (Here I'm reminded of Camus' foreboding metaphors of bodies of water in The Plague for the precariousness and unrest of things in the world.)

Rather than concentrate on the scandal surrounding Piss Christ, it's more productive for us to focus on Serrano's less controversial work, whereby the employment of blood, urine, and semen isn't overshadowed by the power of the loaded sign. If a cultural sign has eroded with time--that is, if it's emotional charge and the myth upon which it depends have dulled and lost meaning--the sign will yield more easily to analysis. Serrano's Female Bust, which depicts the submersion of a kitsch rendition of the Greek goddess of love (resembling both the Aphrodite of Cnidus and the Venus de Milo) epitomizes the evolutionary line from idealized classical sculpture. As one of the West's most sublime aesthetic achievements, the origins of the myth of the goddess of erotic desire is in Serrano's hands settled in with the primeval gratification of an emptied bladder. It's a vulgar end for the goddess to many of her devotees, yet it is one no less eroticized by what the enthusiasts of urine not-so-ironically call "water sports."

One could rush to the coarse conclusion that Female Bust represents some misogynist wish--until it is considered alongside Serrano's other submersions, say Rodin's Thinker. Here the high evolutionary, symbol of wisdom and reason is found drowning in the urinary reflex of some lesser animal. (Serrano claims never to have used human urine for his pictures.) Whereas Female Bust associates the myths of human sexuality and desire with limbic vestiges of the reptilian brain, the human capacity for thought is demystified by Serrano in Piss Thinker. We might as well consider human cognition itself being depicted, or at least that part of it that proceeds from an excruciating, brute recognition of pre-concepts ("necessity" and "release") accompanying somatic-erotic drives like urination. Seen in this light, Serrano's piss pictures pose metaphoric approaches to sublimation in evolutionary theory, making it fitting that the controversies confronting the defenders of Darwin still challenge Serrano in museums around the world.

Serrano's blood pictures, meanwhile, have an altogether different effect on viewers. Rather than eliciting disgust, blood traditionally inspires admiration and idolatry as much as it evokes anxiety. Blood just as readily signifies passion and martyrdom as it does catastrophe and violence, and it's honorable shedding (in times of war) is tied to a sublimation of the sub-human gratification derived from the kill. Blood's depiction can be more easily assimilated into the reality principle than the visualization of excrement (perhaps signifying that the repression and sublimation of the thirst for blood in human evolution came long after the repression and sublimation of scatological pleasure), even as the spilling of blood is commonly justified by socially sanctioned causes (the exaltation of the faith of a saint, the heroism of a combattant slain in the name of patriotism).

Now, with the very real danger of transmitting disease, blood also takes on the uncertainty of contamination and thereby arresting the sign's power to inspire faith. The result is, today a work such as Serrano's Crucifixion, which depicts a sculptural crucifixion group (the crucified Christ, St. John and Christ's mother) submerged in blood, can be interpreted in either of two ways. It might be viewed by Christians as glorifying the sacrificial death of the Messiah--in effect, rendering the crucifixion group holy. But, simultaneously, the non-Christian is just as apt to view the Christian imagery in conjunction with the contemporary fear of corrupted blood as an affirmation of his own skepticism and denial.

Finally, Serrano's seemingly abstract series of cibachromes depict the gender-specific signs of menstrual blood mixing with urine or water, or semen in the spatial trajectory of flight. The signage of both menses and semen have been affected by the hysteria of the epidemic and realistic measures of protection. Menstrual blood, often the cause of the unprepared pubescent girls' fright as her body confronts her awareness, with AIDS becomes the recklessly promiscuous male's terror. But menstrual blood has today also become a kind of legislative enforcer--a reminder that unless the male takes responsibility for the placement of his seed, he may face consequences he is unprepared for. Menstrual blood has always shocked the male (perhaps, as has been classically suggested, because it incites his unconscious fear of castration). But today it also reminds him of the safety of condoms, which renders menstrual blood for the female as a precautionary yet assertive weapon.

In Serrano's signification of semen, milky fluid is seen photographed in trajectories of flight. It's not difficult to imagine what sexual activities are implicit in this minimal representation. As a result of safe sex practices, sexually active adults have witnessed more semen fly than likely ever before in history. Prior to the need for practicing safe sex, semen almost invariably was visualized (or really conceptualized) deposited and concealed interiorly. Now, however, as a result of the danger involved in sexual contact, aside from being released in condoms, semen is ejaculated more often in the open. Shooting semen has become as synonymous with safe sex as it has long been associated with the porn industry's climactic shots, and Serrano's photographs can, in this context, be seen as an affirmation of both safety and porn as a consequence.

Of course, by traditional institutions and values, images of flying semen can only represent de-sublimation, as it embodies the spent libidinal energy and desire "properly" to be sublimated. Serrano's Ejaculate in Trajectory as picture of the religious "wasted seed," brings the social and psychological processes of sublimation and de-sublimation full circle. Such a work traverses a territory that can never be completely sublimated: the psycho-somatic region of erotic gratification. As an interpretive work of art, Ejaculate in Trajectory signifies pleasurable not procreative sex, and thereby literally as well as figuratively flies in the face of those whose puritanical values reserve sexuality for procreation, not recreation.

By picturing sublimation and de-sublimation as a composite yet inseparable process and idea, Serrano has, like the secular culture he mirrors, adapted Freud's theory of sublimation to the individual will that understands the rules and tools of civilization are to be personally mastered on one's own terms rather than suffered for being imposed from above. Freud's reality principle can be altered to satisfy a wish not only according to the conditions imposed by the external authority, but as well by the conscious and personal volition of individuals (as has long been the premise and intended end of psychoanalysis). And as an unconscious desire cannot be acknowledged without an experience of shock and denial (since the mental apparatus functions to reduce tension and pain), any attempt to publicly expose the repressed psychic energies of society (such as those made by artists) will be met with resistance. This doesn't mean that all shock is activated by the airing of repressed meanings; many cases of shock are, in fact, effected by real danger. But any scandal effected by the art of Andres Serrano results almost exclusively from a viewer's premature exposure to the components of that viewer's own mind.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.