Here is my analysis of the “Dawn of Man” sequence from 2001: A Space Odyssey:

Following essay written by Daumoun Khakpour.

The “Dawn of Man” Sequence from 2001: A Space Odyssey is a sublime example of ‘Pure Cinema’. Kubrick completely omits dialogue, and relies on visuals and musical to deliver one of the greatest and well known openings in film history.

Movies are a visual language. It’s an idea that has been parroted since the inception of the motion picture.

What is Pure Cinema?

“Pure cinema”, can be defined as cinema were the visuals and editing are emphasized and dialogue is either completely omitted or used sparingly.

Furthermore, each and every frame or shot of the movie is built on top of each other, either by adding a new element to the story or providing new information. This visual element can be aided by sound effects or music, but the dialogue itself would be excluded.

The original theory of Pure Cinema was originally called Cinema Pur and coined by theorist and filmmaker Henri Chomette in the 1920s. This method was adopted early on by filmmakers like Rene Clair, Dziga Vertov, and Henri Duchamp. They believed that cinema should returns to its original roots, where the images themselves through visual composition and movement would provide a sort of visual poetry.

These early adopters would rely on visuals, in camera techniques and editing, to heighten and draw attention strictly to the visual elements. Chomette himself also released a short film aptly titled ‘5 minutes of pure cinema’. In this short film, a series of images are superimposed or laid upon one another with stylized lighting to establish a mood or feeling.

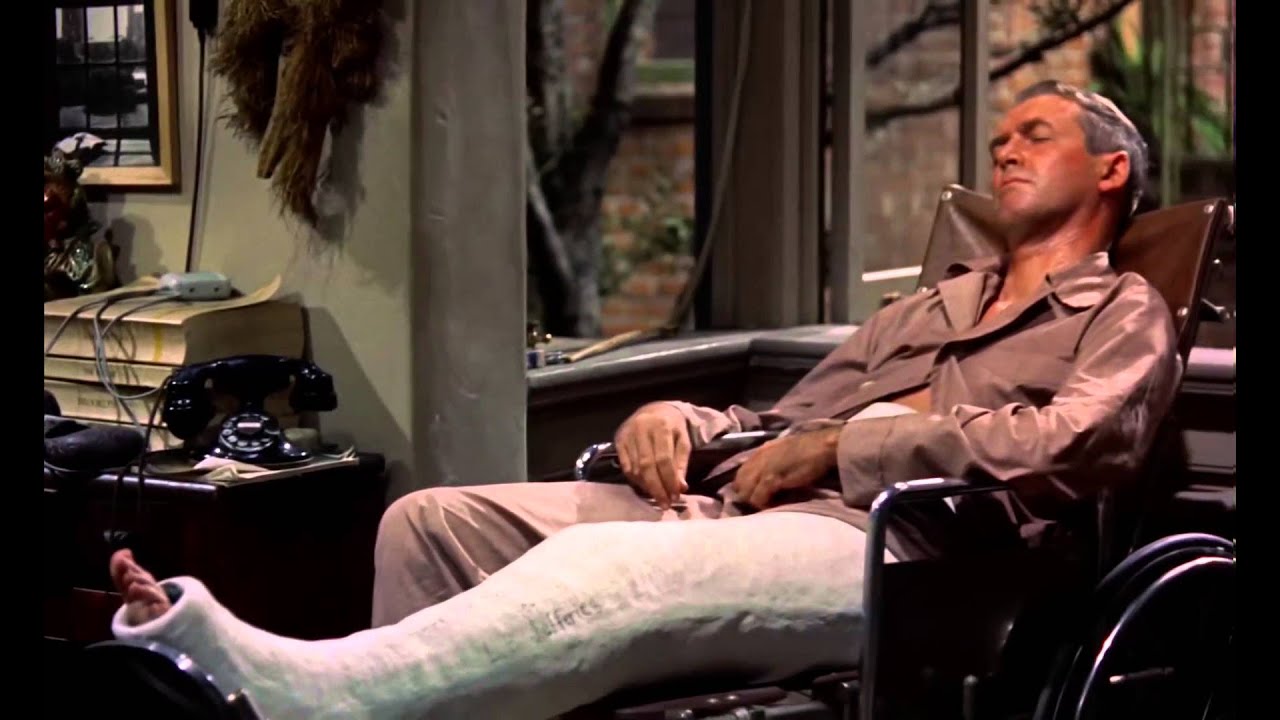

Hitchcock also prescribed to this notion of using strict visual language to further story, establish character or explore themes. For example take note of the iconic opening scene in Rear Window.

We are presented with a nearly three minute single take that contains no dialogue outside of a radio and kids playing in the distance. The camera moves throughout various levels of the apartment building while showcasing the residents of the apartment block.

The camera finally settles in the protagonist apartment. He is both sweating and facing away from the window, unlike the rest of the inhabitants of the apartment building who face towards the outside world. This both sets up the heat wave and how he has closed himself off from everyone else.

The camera then focuses on his broken leg, which becomes a focal point throughout the film. From there we move to a broken camera, again establishing his passion, a car accident, and a hint to how his injury occurred, then finally to various images of a young woman.

By showing the broken camera and then revealing the image of the car accident, we understand the passion and drive of the main character. He was willing to injure himself to get the perfect shot, his driven nature is foreshadowed, as he will do almost anything to solve the murder that happens later in the movie. No dialogue needs to be spoken, we understand who this person is and what he is willing to do by pairing these images and shots together.

This is an example of how Pure cinema works, where each shot builds off each other and provides new information or furthers the story. Again, this is all presented without the use of dialogue as a tool for exposition.

So, how does this relate to Stanley Kubrick?

Stanley Kubrick’s use of Pure Cinema

Let’s focus on how Kubrick utilized the idea of Pure Cinema first defined by French Filmmakers in the 1920s to create one the most iconic moments of cinema since the creation of celluloid. Specifically, I will be looking at the “Dawn of Man” sequence from 2001: A Space Odyssey, and how a series of images, sound effects, and music are harmonized to present a story without the use of dialogue and thus creating “Pure Cinema”.

Perhaps the simplest question to ask right out the gate is “Why do we understand everything that is happening in this sequence?”

This again is built on two components: First, each image should build to the next one and second, every subsequent image should be telling us something new; either by giving new information or pushing the narrative forward.

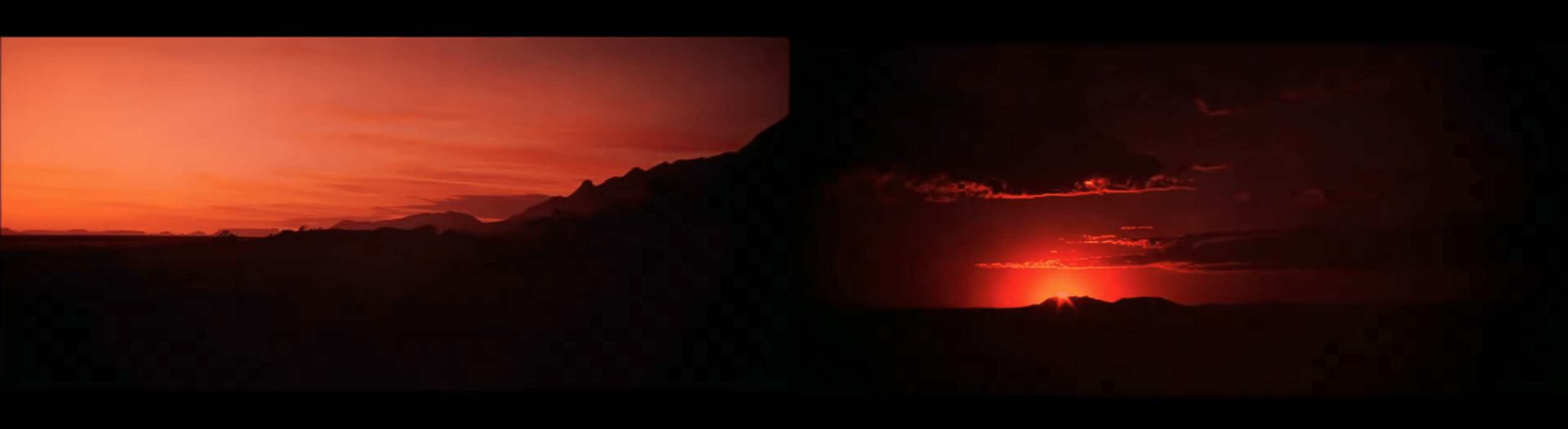

As we keep that in mind, let’s look at the first shot of the sequence which serves both as literal and a metaphorical function in the film. A pink and amber sky towers over black mountains and a desert valley beneath.

The dawn of man is presented at literal dawn. We are showcasing possibility and the potential of the future and the hope that encompasses it.

The next couple of shots are a tighter variance of the first one, wherein we focus on the mountain.

Next:

We finally arrive to a shot that is at the same time of day in the first shot, and another which could be sunset.

We are then inferring a passage of time, how each day bleeds into another, almost as if the inhabitants are living in a stasis, the passage of time goes on without much fanfare.

This goes on for a series of shots again establishing where the location is, the sunset and then finally we shot changes to underneath the mountain, as we get closer.

The sun rising and falling for each shot, again stresses the passage of time and how little has changed both for the environment, and potentially the inhabitants that live around the mountain. More importantly as this was filmed on 65 mm and meant to be viewed on the largest screen possible, we are now immersed and aware of where we are.

We have been transported to the distant past, one without electricity, technology, or running water.

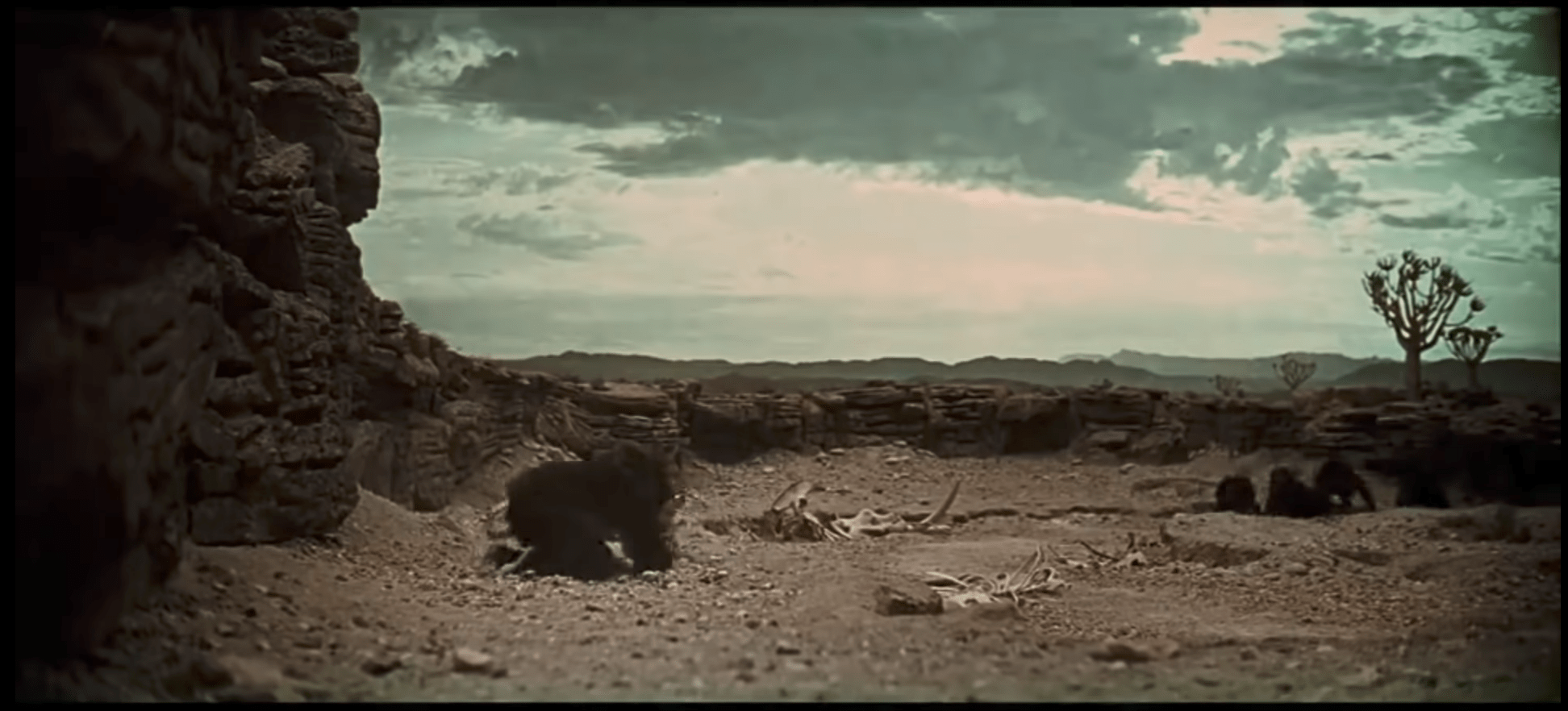

In the a next series of images we are made aware of the landscape once again, how it is sparsely populated, without many living creatures both humanoid and not. We are finally given a point of view shot that establishes new information as to where specifically the scene and actions will take place. The audience is looking down on a barren and dense environment. The inhabitants would do anything to survive, they are adaptable and resourceful.We are meant to experience this world, our lips should crack as the dry air surrounds us, as the sun bares down on our necks.

The next shot showcases what looks to be a skull of an ancient animal, again cementing this as the past, which is both an unforgivable and almost unlivable environment.

To live here you must be strong, adaptable and have a strong desire to live or perhaps need to work together with whatever other species live in close proximity.

From there we go to a series of skeletal remains from a long deceased species and then a shot of what looks to be apes, then some tapirs, then the two species together. Then again, both Ape and Tapir around foliage in the form of shrubs. Then apes eating the shrubs, finally a compressed longer couple of shots with bones in the foreground.

This heightens the gravity of the scenario and the environment these creatures are living in; it is a matter of life and death.

This is Kubrick at his best and a showcase of his genius. In a series of images we have developed what type of landscape this is, how long the creatures have been there, their relationship to each other, the food source available and the harshness of the environment is reestablished. Again much like the theory of Pure cinema, each image builds off the last and provides new information; this is “Pure Cinema” developing.

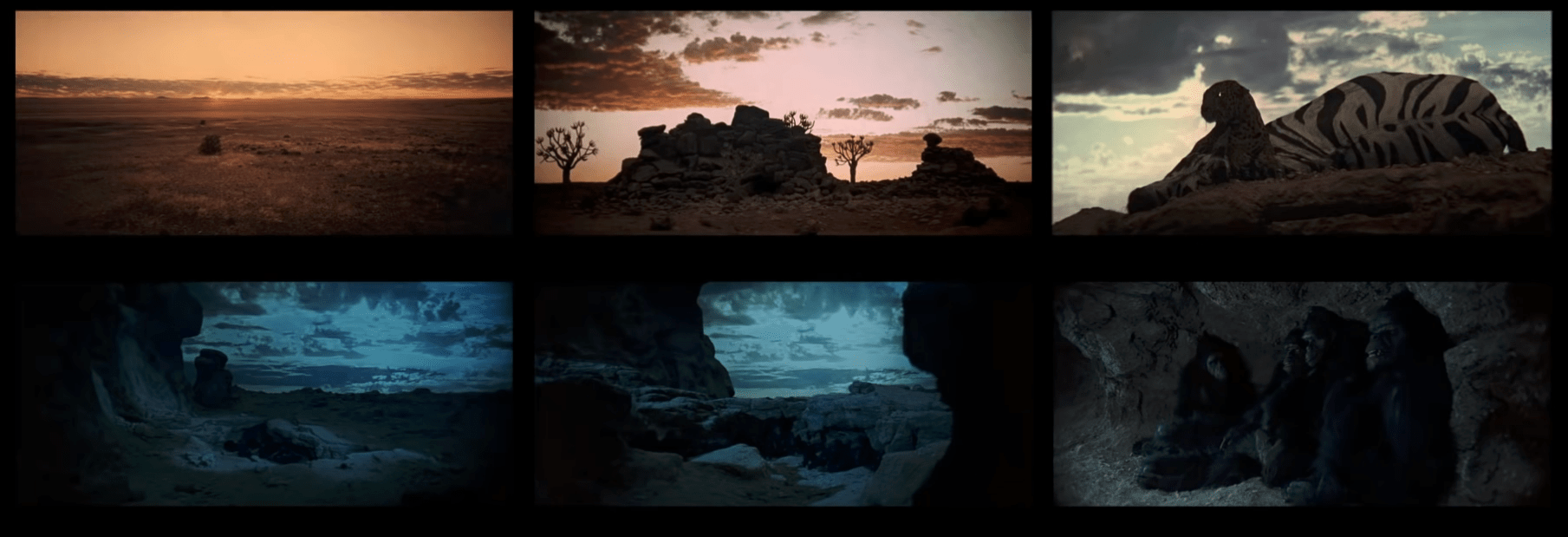

Then finally the sequence develops as we have a hint towards conflict, as the resources (shrubs) dwindle, the ape asserts its dominance and territory while attacking some of the tapirs. We have established a food chain.

However, our expectations are subverted as the ape is attacked by a Jaguar, the food chain is now re-established.

Next up we are provided a series of images by a watering hole as we are finally introduced to a series of close ups of apes that will serve later as heroes later in the story. These close-ups foreshadow their importance in the story.

In the next consecutive series of shots we are introduced to the villain apes who look down upon the hero apes. This foreshadows the power dynamic. Later on they overpower the hero apes and take the watering hole for themselves.

We immediately associate and empathize with the lower of the two groups and we entrench ourselves with who we literally see as the underdog. These shots continue as the rival group becomes larger and dangerous as they inch closer. Furthermore, Kubrick does not complicate the action or change the angle of the shot, we are ensconced within the 180 degree rule so we can clearly see which side is which.

The antagonists gain an immediate victory of the watering hole as our protagonists are edged out.

Kubrick then cuts to a series of evening establishing shots to indicate that both the day is changing, but also the peaceful nature of these apes. The natural order has been thrown out, and something new will arise with the next day. We then see a Leopard perched high above on a perch with its prey.

Again, we establish that the Leopard is literally above the rest of the Apes in regards to the food chain and societal order, and then we cut to our protagonist of Apes that are in a cave, quite literally underground or on level ground, as they ponder what to do next. We cut back to the sun setting, establishing again a change is coming and that the once repetitive day in and out of early human ancestor life will be disrupted.

It is the following morning, our hero ape awakens and we reveal the monolith. Through a series of images, we reveal the apes agitated by the monolith and unaware how to perceive or acknowledge this new unnatural intrusion in their life.

We then cut to a low angle shot of the monolith as we look up, with the sun and moon above it. Again we have established the power structure, this monolith, as it has arrived from an even higher perch, higher than the rival apes or the leopard; so high, it is not even from this world.

We cut to another day but there is no dissolve, this is no longer a languid placid way of life, we have entered an urgent state of life. More images of landscape and then finally our hero ape as he starts to play around with a series of bones, no tapirs or shrubs are seen.The world has diminished and the focus has become primarily on this group and their leader.

Additionally, by match cutting with the monolith and the ape learning to use a weapon out of the skeletal remains, our brain subconsciously pieces these two elements together, with the help of the music.

Here, we cut to to to the tapir following as the power dynamics have been reversed, and another close up of the bone bashing the rest of the skeletal remains; the bone has been repurposed.

The ape is now on top of the food and societal chain as man’s ancestor learns to kill.

We then follow this with another series of images.Our hero apes learn to eat meat and no longer eat the scarce remnants of foliage. This is not a forced choice, but rather they relish and enjoy the taste of their newly found food source.

Next up.our hero apes have quite literally taken a position of power as they are on the rock ridge looking down at the antagonist apes near the watering hole.

Their weapons are drawn.Our villains do not back down, so our hero decides to confront him with the weapon. This starts a minor scuffle with the villain attacking, till he is struck down by our heroes weapon.

Kubrick here makes it a point to not show the villain as definitively dead, as dread and a feeling of uncertainty washes over us. Our hero is “triumphant” our ancestors have learned about the act of violence and thus the balance of life has changed.Finally our hero ape turns towards the rival ape leader and says something, which we may not be able to verbally understand, but we get it.

Kubrick here has established the beginning of violence and the source of human conflict, the nexus of the next thousand years as the cynical cyclical pattern of violence has been born.

The movie was made a little over 20 years after WW2, during the heat of the cold war, and on the dawn of the Vietnam War.

The ‘Dawn of Man’ sequence has about 105 shots and these shots last an estimated average of 8.5 seconds. The entire film itself only has 611 shots with a run time of 142 minutes, so each shot must be carefully considered and composed, and the editing must reflect this.

One could argue that modern cinema has skewed towards the trend of rapid cutting and the shot themselves no longer carry the weight of what they once did. One could argue that the reliance on individual shots without the use of repeated angles, with minimal editing, and no dialogue would bore modern audiences but the ‘Dawn of Man’ sequence tells us so much in that 10 minutes about the nature of man, our past, and ultimately our future.

In an era where the images matter less than the new technology that surrounds it, perhaps we should pare down and focus on the visual details presented in the frame.

Lastly, we can clearly see how effectively ‘Pure Cinema’ works here, when a filmmaker goes into a film with a clear understanding of their message and the themes they would like to express, we can have revolutionary cinema that stands the test of time. However, this is in part effective by seeing it on the largest screen possible, as every detail is made clear, every edit highlighted, and thus we have a better connection with what is being shown.

Again, every shot builds on top of each other and every shot presents new information and develops the story; no redundancy or multiple angles. This is how ‘Pure Cinema’ works.