Stanley Kubrick | 2hr 19min

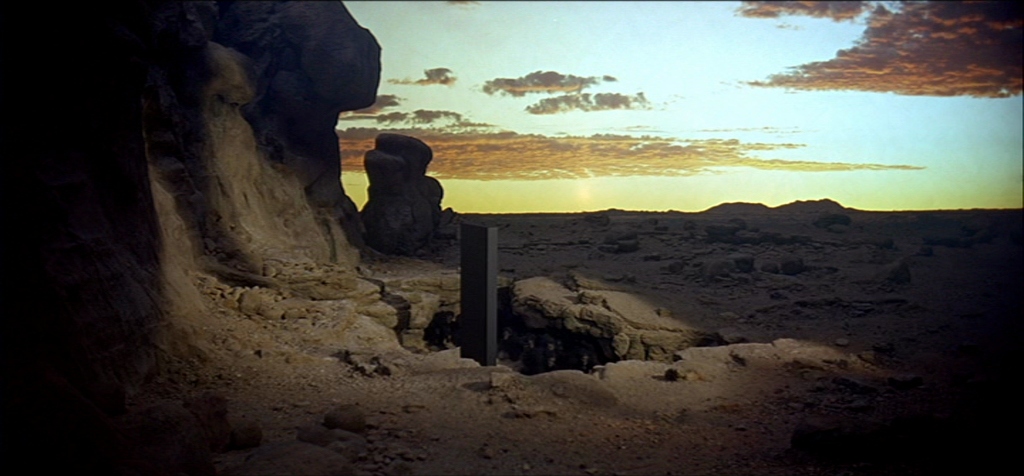

Beyond the apparent plotlessness of 2001: A Space Odyssey, and within its constant shifting of perspectives, there is a single, guiding figure uniting the eons of time that pass through Stanley Kubrick’s awe-inspiring cinematic vision. The monolith may only appear for less than ten minutes of screen time, and yet is our most consistent companion in this film, curiously emerging at each new leap in evolution as the human species moves steadily further away from home. It towers above them as a large, black rectangular prism, bearing no mark of its purpose or origin, yet the mystery it projects is compelling. It is as much a celestial phenomenon as the stars, planets, and moons above us, and even aligns with those astronomical bodies in perfect symmetry as if writing our biological and technological advancement into the inextricable code of the universe.

As much as primates from across the evolutionary spectrum are driven to reach out to it in wonder though, it projects a soul-shaking fear from its imposing aura. Kubrick’s decision to replace Alex North’s score with pre-existing music was harsh yet inspired, and in this instance, he associates the monolith’s unnerving presence with a haunting, atonal requiem by classical avant-garde composer György Ligeti. The first three times we encounter it, sopranos and mezzo-sopranos waver over a twenty-part chorus that almost seems to be screaming in eldritch terror, producing a dissonant tone that simultaneously beckons the human race into an unknown future and exposes the smallness of their existence.

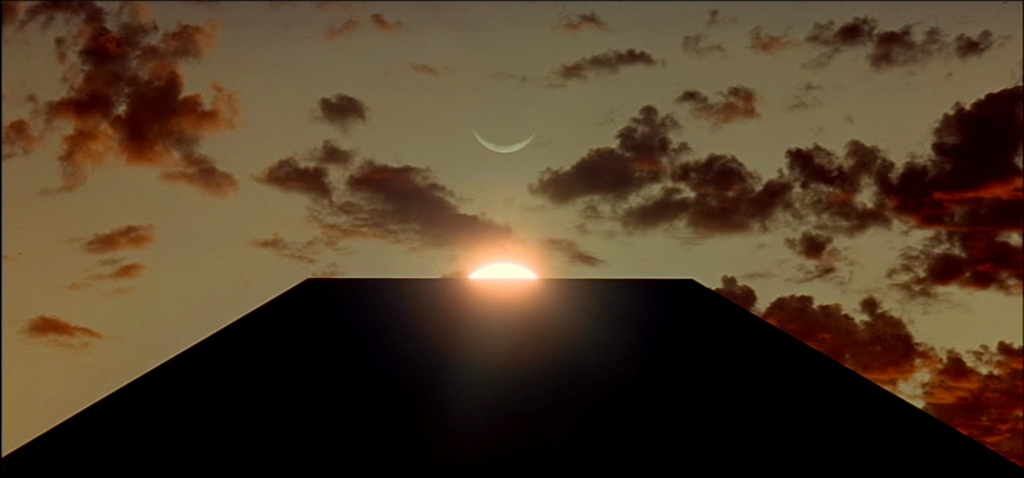

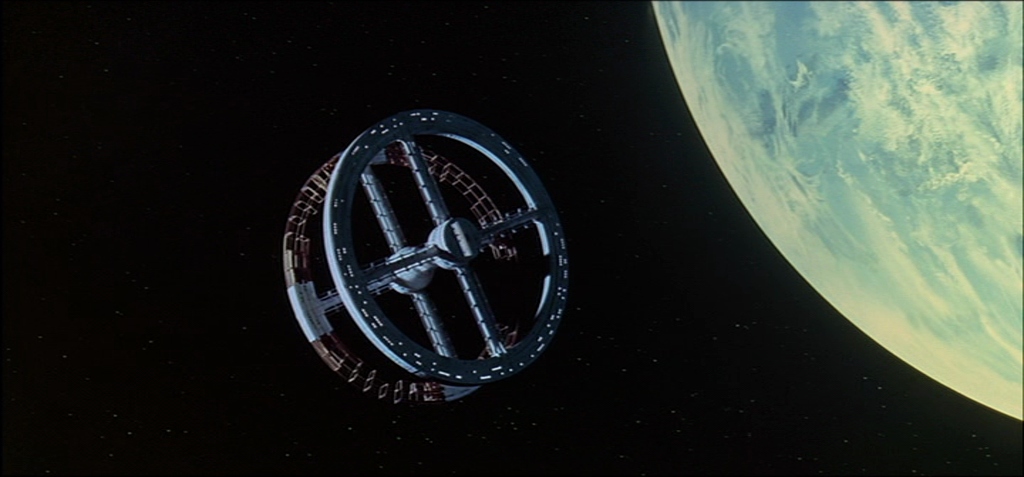

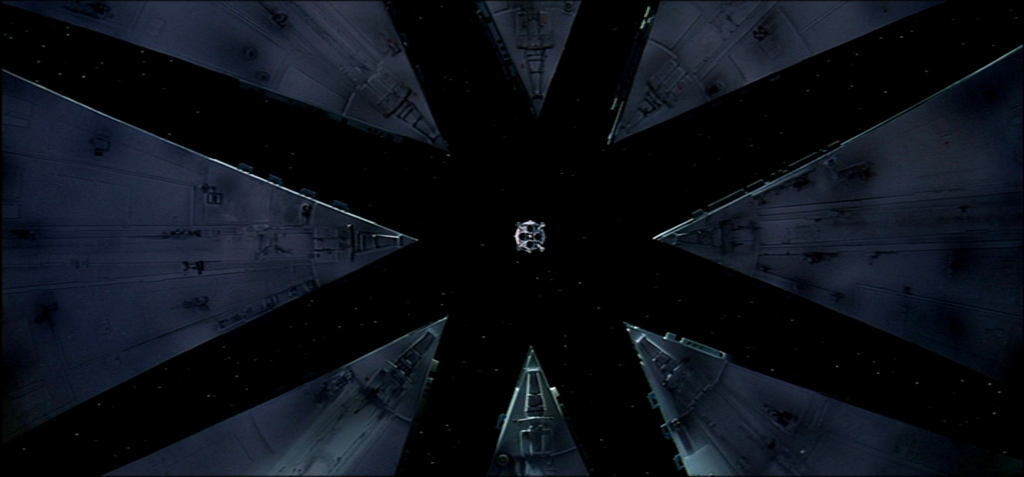

The only instance we encounter the monolith without this accompanying music is in its fourth and final appearance, bookending the film with Richard Strauss’ majestic orchestral piece ‘Also sprach Zarathustra.’ More specifically, it is the opening ‘Sunrise’ fanfare that builds to a marvellous crescendo over these twin scenes of human evolution, brightening Kubrick’s austere sterility with bursts of classical artistry. Likewise, Johan Strauss II’s iconic ‘The Blue Danube’ waltz is set against a balletic montage of spacecraft twirling and drifting through outer space like dancers on a stage, imbuing these artificial constructs with a humanity that has not been lost within the centuries of scientific progress. Kubrick’s soundtrack is nothing less than ground-breaking, boldly diverging from the tradition of original scores five years before American Graffiti would correspondingly popularise using pop and rock songs as film music.

Within 2001: A Space Odyssey though, art is not the sole bedrock of life’s essence, but just one pillar of humanity’s evolving sophistication. As much as Kubrick is branded a misanthrope for his statement on humanity’s inherent evil in A Clockwork Orange and his cold treatment of history in Barry Lyndon, his belief in our species’ potential to keep outdoing itself with enormous feats of intellect and willpower transcend all of that, tracing that lineage right back to our roots as primitive lifeforms.

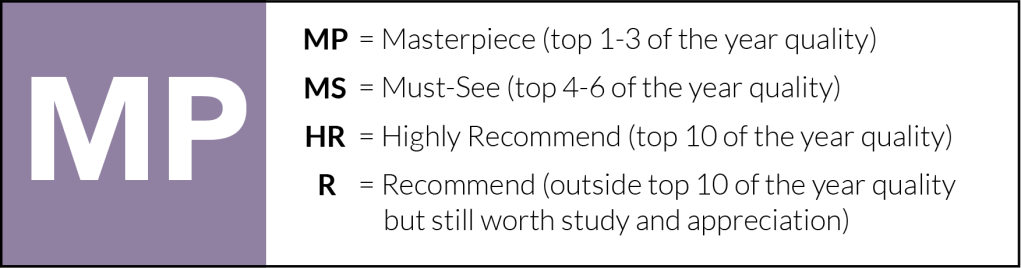

This is where Kubrick’s ‘Dawn of Man’ sequence opens, where our vegetarian ancestors hide from predators in caves, howl at rival clans trying to drink from the same waterhole, and live peacefully alongside tapirs. With the first arrival of the monolith also comes their initial step towards becoming the humans we are today, drastically shifting their place in this world of pure animal instinct. When one primate discovers how a bone might be used as a deadly weapon against his foes, infinite new possibilities open up – no longer do they have to simply run from danger, or feast on local plant life. By fashioning tools out of available resources, they effectively become the dominant species of their environment, and win this round in the game of natural selection.

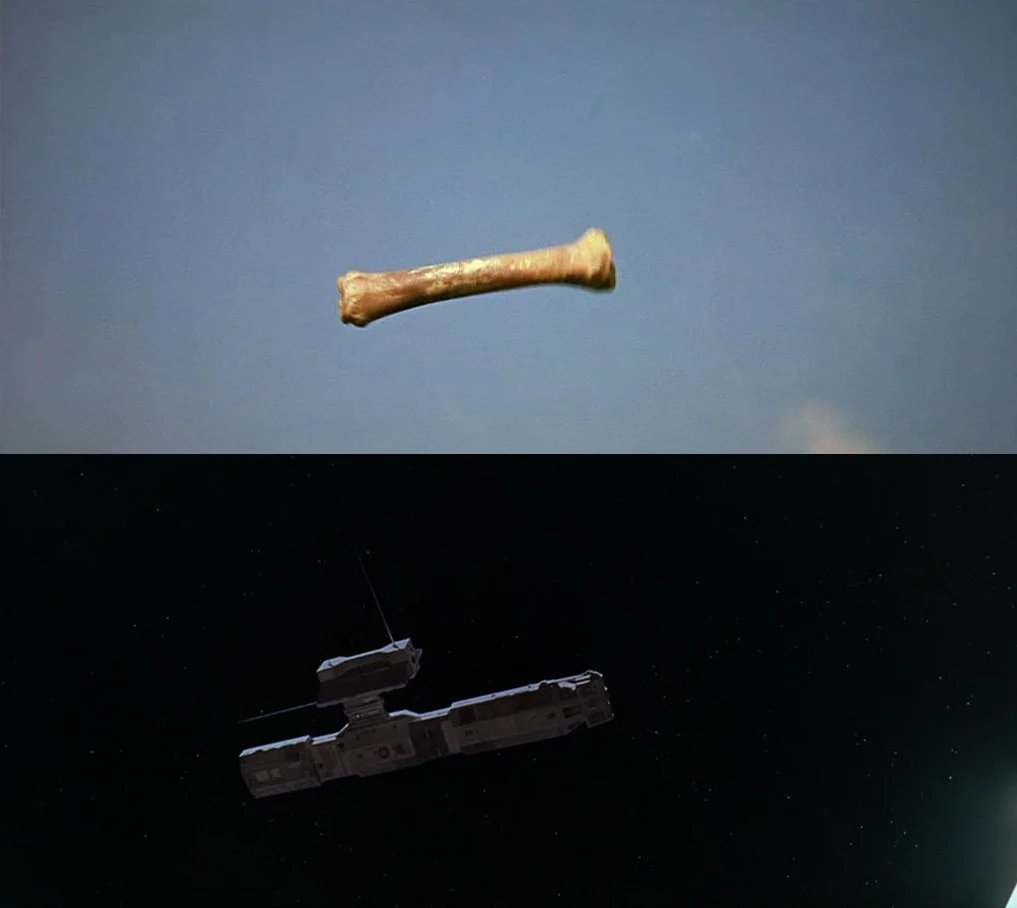

The graphic match cut which then leaps ahead millions of years may lay claim to the single greatest edit of film history here, connecting humanity’s past to its future by a pair of technological instruments – the bone, and a satellite in orbit above the Earth. The history of an entire civilisation is economically laid out in this cut, defining these distant relatives as members of a single family bound by their instinctive drive to keep pushing boundaries beyond what their bodies are capable of on their own. That their reliance on manufactured tools threatens to erase their human warmth only concerns Kubrick to an extent. His direction of actors to communicate with the same deadpan sterility to both colleagues and family members may pose a demoralising vision of the future, but on the other hand, he also isolates something unique about humanity beyond its social relationships. Even when these characters are millions of kilometres from loved ones, the drive to simultaneously survive in the most hostile environments and pursue a deeper knowledge of the cosmos endures, defining the wondrous evolution of life at its most basic level.

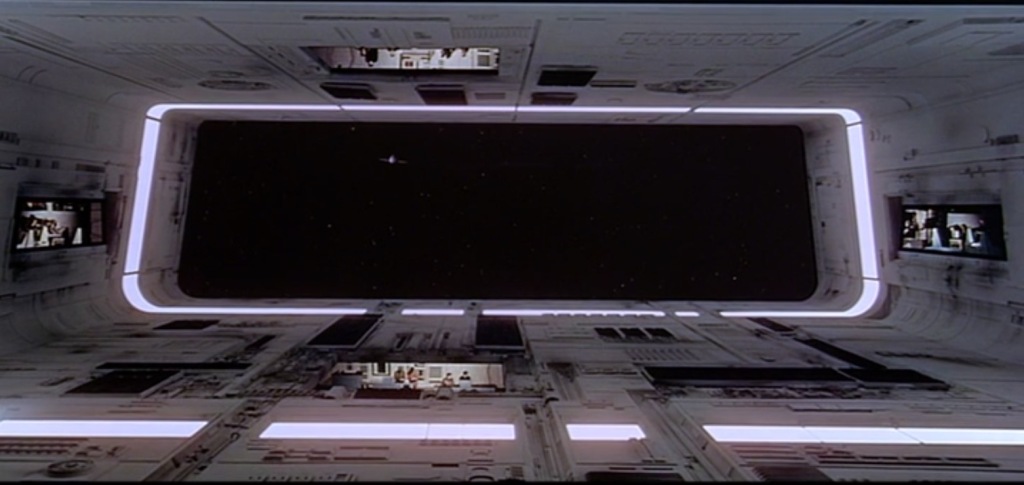

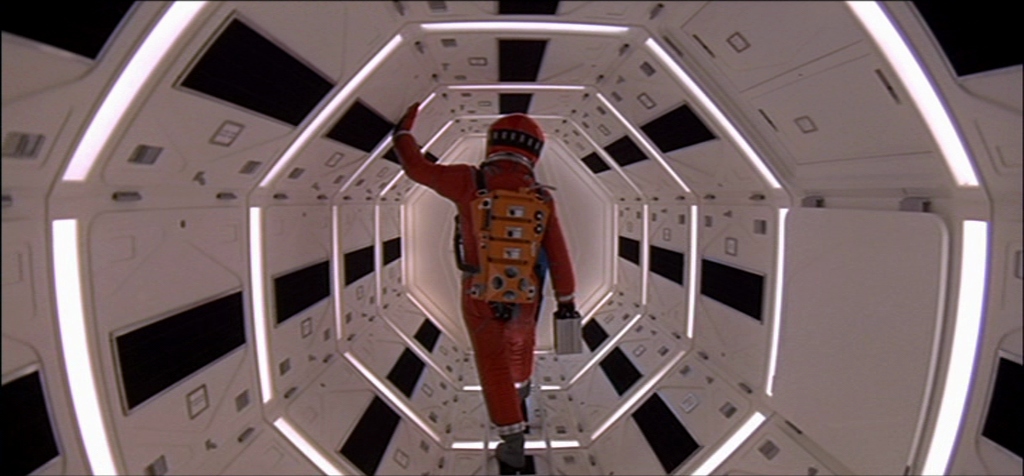

Through sheer aesthetic precision and formal rigour, Kubrick adopts this ambition on every level of his film’s construction, crafting a staggering work of art that measures up to the cosmic scale it is shooting for. His regular cinematographer John Alcott may not get enough credit for the gorgeous African landscapes on display in the ‘Dawn of Man’ sequence, though it is quite clearly Geoffrey Unsworth who comes out looking even better in this collaboration, coordinating the camera with revolving sets that seem to disobey all known laws of gravity. As astronauts walk up walls, across ceilings, and around the circumference of rotating sets, he and Kubrick leave us awed at sights of humans accomplishing the impossible, and lay the groundwork for the sort of mind-bending practical effects that Christopher Nolan would later innovate in Inception.

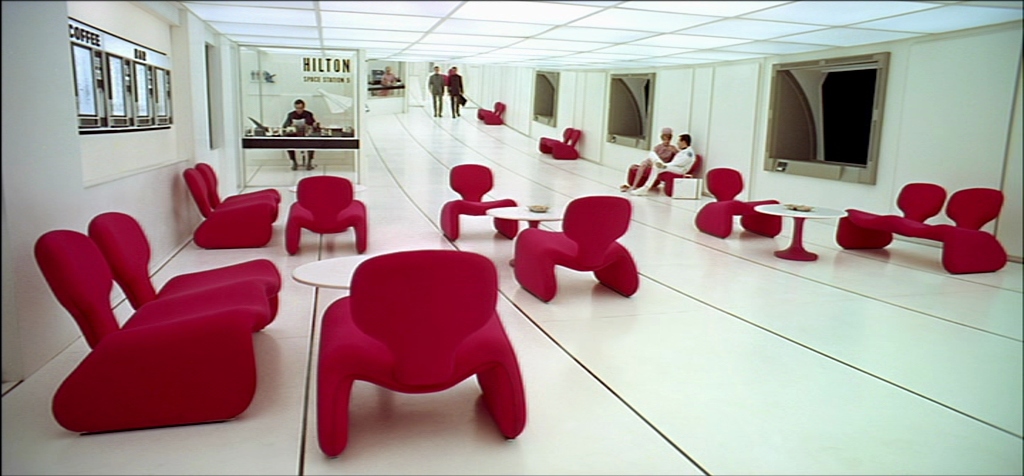

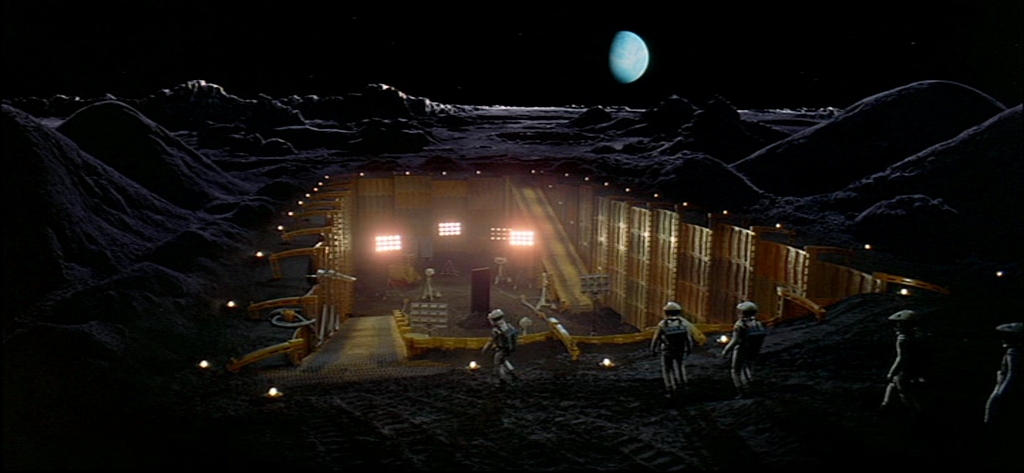

When oblique angles that divorce the camera from any upright orientation aren’t Kubrick’s focus, he is often using symmetrical designs as the basis of his visual style. There is even an element of silent filmmaking we find seeping into many of his shots, as he frequently returns to matte paintings and miniatures that evoke the godfather of science-fiction epics, Metropolis. Lengthy passages of time are spent in the vacuum of space gazing at these vast metallic vehicles from a distance, but even inside docking bays and on the moon’s surface we find impressively intricate models, often with tiny humans superimposed for scale. Meanwhile, neo-futurist aesthetics shape Kubrick’s geometric interiors, with red Djinn chairs decorating a stark white corridor where a group of bureaucrats meet, and rounded corridors mirroring identical textural details across both sides of the frame.

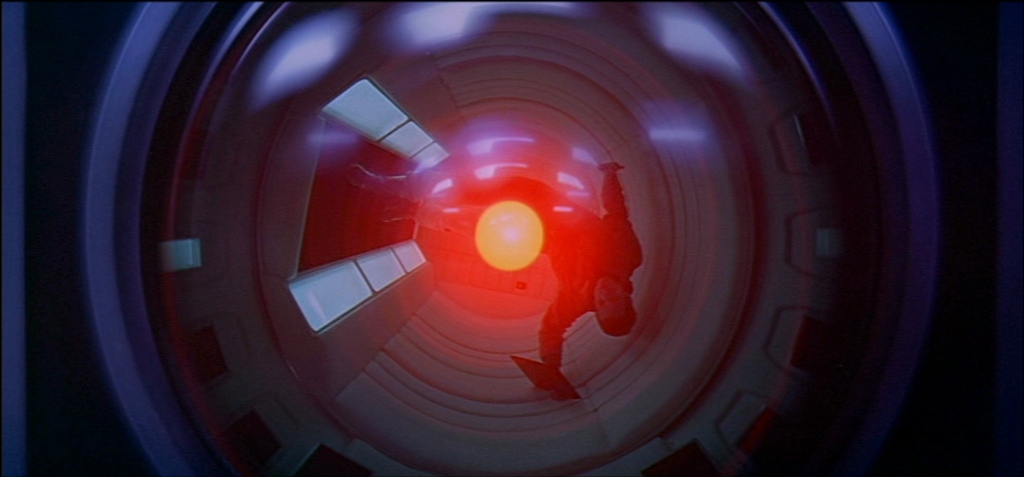

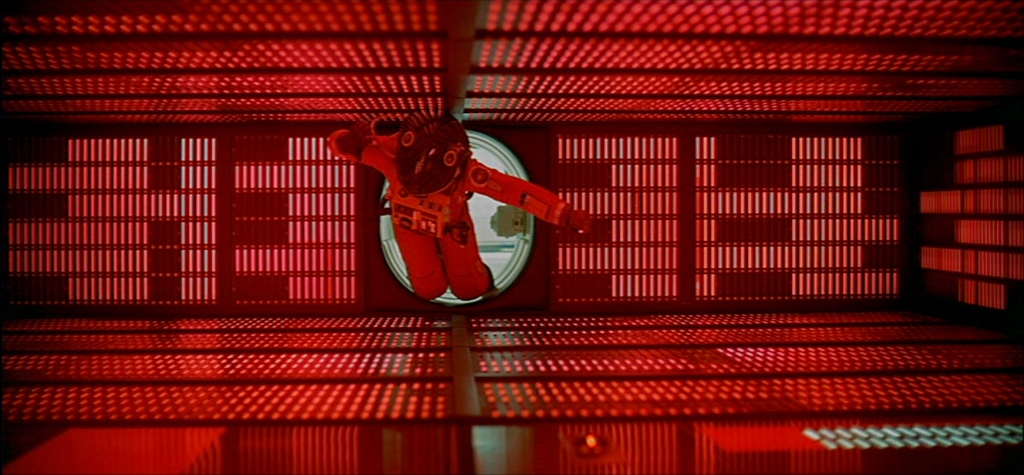

The presence of red hues that Kubrick weaves through his mise-en-scène is impossible to ignore as well, flooding rooms with vibrant washes, bouncing control panel lights off the characters’ faces and helmets, and of course embodying pure danger in the terrifyingly simple design of HAL 9000. This unblinking, all-seeing crimson dot is essentially the brain of the ship that Dr. Dave Bowman and Dr. Frank Poole are travelling on to Jupiter, and is tasked with ensuring the mission’s success.

When it comes to narrative power, the ‘Jupiter Mission – 18th Months Later’ section is easily the most traditionally structured, as for the first time in the film we find characters running up against a clearcut villain. This brand of artificial intelligence is supposedly infallible, and yet when it makes a technical error Dave and Bowman are forced to consider shutting him down in a private discussion that they do not realise HAL can lipread every word of. Douglas Rain’s monotonal line deliveries as the supercomputer are chillingly calm as it reasons with utmost rationality why it must kill all humans onboard, but given the self-preservatory nature of its actions, one must also question whether HAL has developed the natural flaws and instincts of living organisms.

In a stroke of formal brilliance, we are reminded that Kubrick set this conflict up back in the ‘Dawn of Man’ sequence. Domination over other life forms is an integral part of evolution, and violence is the quickest path to achieving that, thus reflecting the ape’s murder of their rival at the waterhole in Dave and HAL’s struggle to respectively assert themselves as the superior species. Perhaps HAL has gained enough sentience to experience real fear as Dave disconnects him, or maybe he has just gathered enough insight into weaker minds to understand how one might manipulate their emotional vulnerabilities. Either way, as Dave enters the red processor core bathed in HAL’s brilliant red light, the supercomputer’s pitiful begging ironically expresses the most human sentiment of any character in the entire film.

“I’m afraid, Dave. Dave, my mind is going. I can feel it.”

The stinger in this scene is the ailing rendition of the folk song ‘Daisy’ that HAL sings as he reverts to his original settings, displaying the tiny piece of humanity contained in his basic programming which now dies with his slowing, deepening voice. Once again, the elimination of a foe has made way for our species’ climb up the evolutionary ladder, guaranteeing safe passage to Jupiter where yet another monolith waits to be discovered.

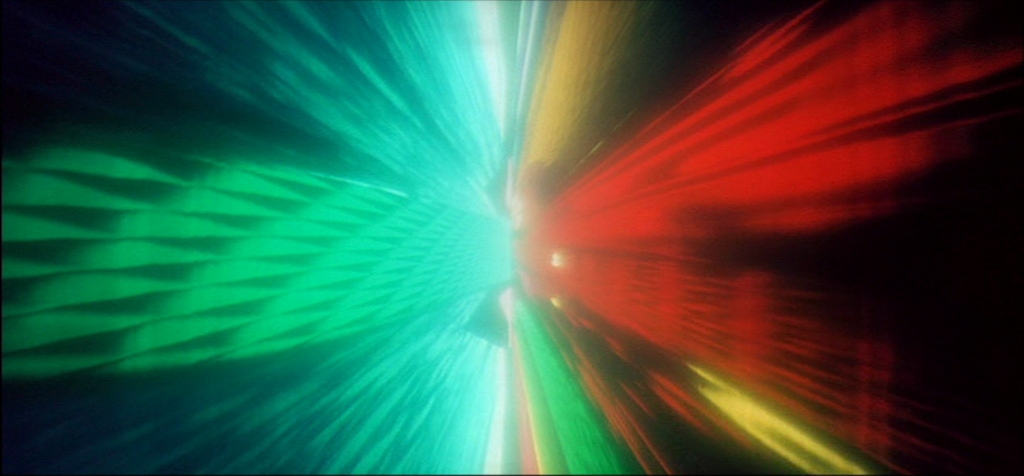

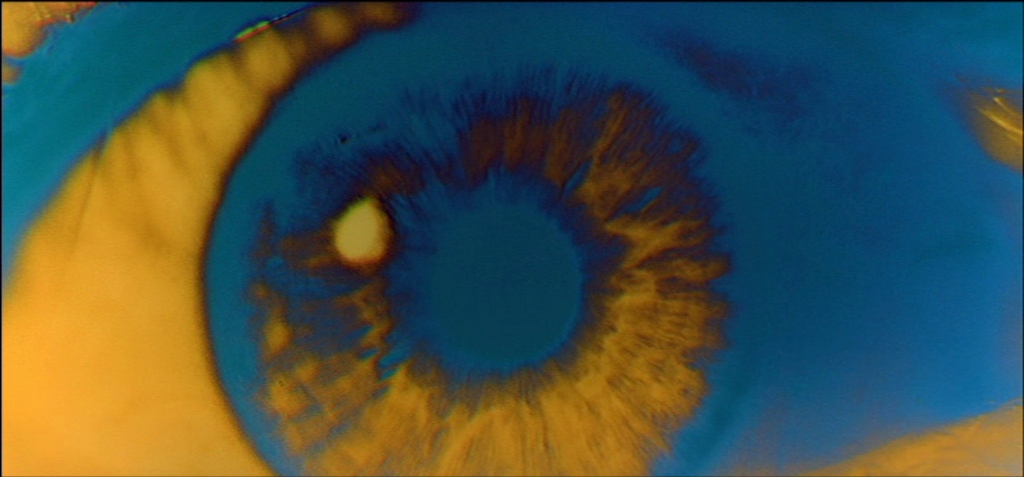

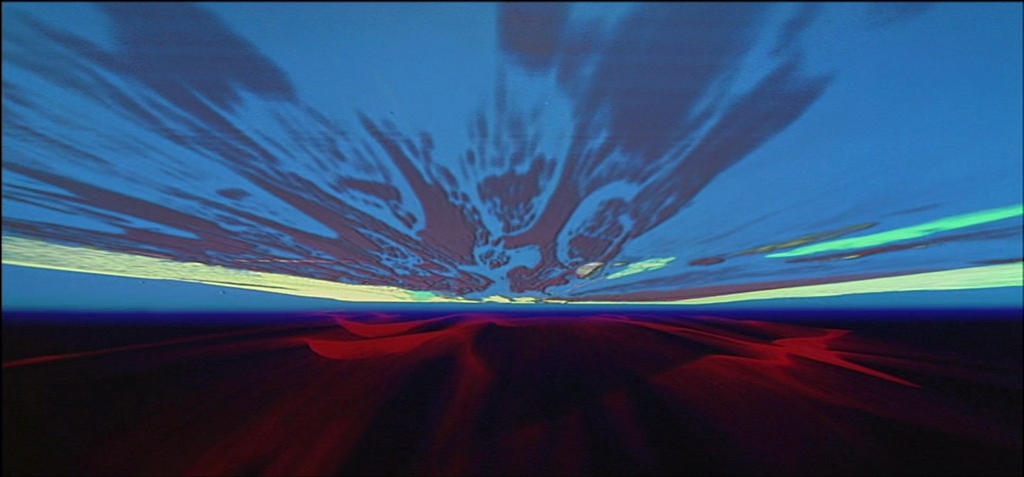

The transition that Kubrick makes from what is a relatively straightforward plot into the most avant-garde filmmaking of his entire career is abrupt, yet exactly what we need to enter the right mindset for what’s to come. Luminous colours from all across the spectrum explode in a vortex of light as Dave is sucked through a wormhole near the Jupiter monolith, and Kubrick enlists the help of visual effects supervisor Douglas Trumbull to execute this psychedelic Star Gate sequence. Fluorescent dyes, smoke, folded lenses, and slit-scan photography are the primary tools in his arsenal here to create galaxies, stars, and waves of plasma swirling through space, though the exceptional beauty of this spectacle is also jarringly offset by the intercut freeze frames of Dave’s painted, contorted face as he is pulled through it all. The bizarre look of the alien planet he soon finds himself flying over is achieved through similar technical experimentation, colouring the negative film prints of skies, deserts, canyons, oceans, and mountains, as well as the extreme close-ups of his eye that change hue with each terrified blink.

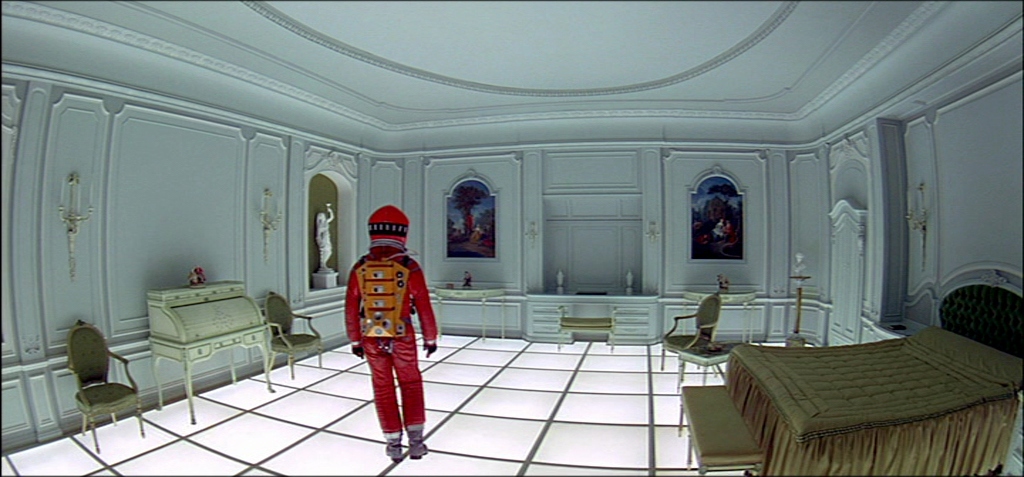

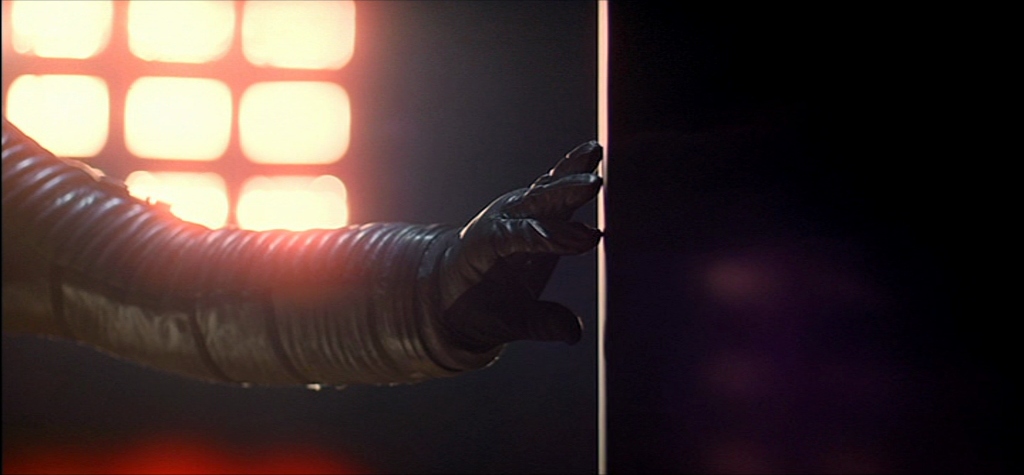

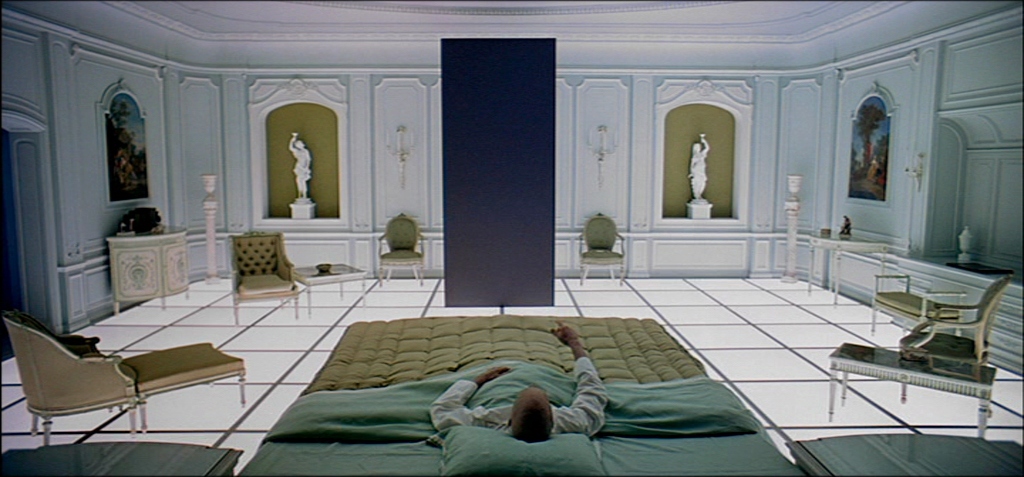

Lasting almost ten minutes, this hypnotic montage is enough to disorientate us completely by the time we reach Dave’s last destination – the location that each monolith was pointing to along the way. The small, windowless room he lands in might almost resemble a neoclassical home with traditional furniture and art were it not for the nonsensical, inhuman design of everything else, from the lights beaming up on the floor to the clinical white palette which consumes it all. If this is where he has been led by higher alien life forms, then it could very well be the enclosure they have built for him, attempting to replicate his habitat in much the same way a zoo might for their caged animals. Foreign noises reverberate just outside the walls, indicating the presence of something observing him further, while time slips away like water. Kubrick’s editing is precise in its perspective shifts, in each instance catching the glimpse of another figure within Dave’s new home, only to discover an older version of him who we latch onto. Who should he meet at the end of his current life as well, but the monolith which has been guiding him this whole time? Just like the apes and the astronauts who found it on the moon, he reaches out, ready for whatever comes next.

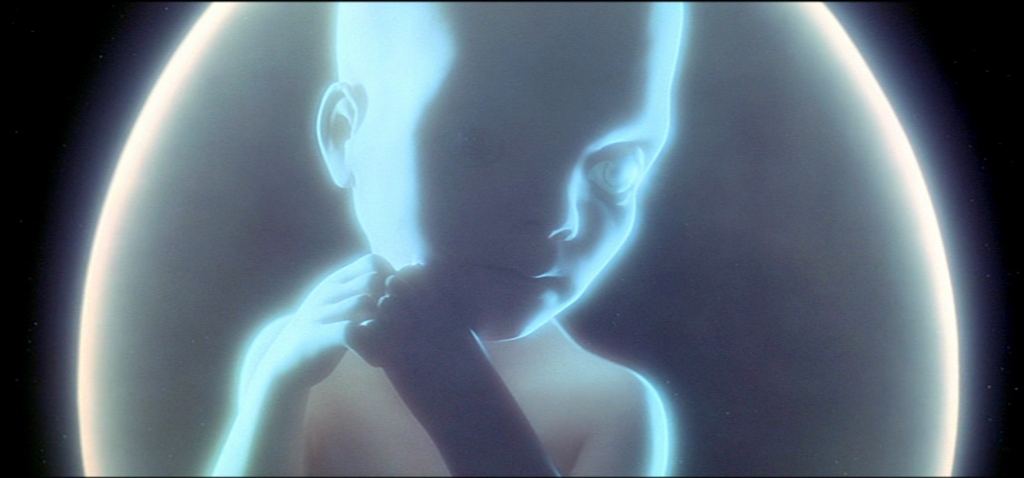

The newly reborn Star Child that Dave evolves into has the uncorrupted, infantile appearance of a human baby, and yet its wide eyes gaze upon its home planet of Earth with a knowing enlightenment, prepared for new beginnings. That this is the third and final form of humanity as depicted in Kubrick’s film is subtly crucial to the ternary structure that he has been building from the start, integrating it into the three dividing chapters, the three versions of Dave who live in the alien enclosure, and the three astronauts hibernating aboard the Jupiter ship. Even György Ligeti’s requiem plays on three separate occasions with the monolith, save for its aforementioned final pairing with ‘Also sprach Zarathustra’, in which he conclusively separates it from the discordant terror of the unknown and opens us up to a wilful embrace of the transcendent. With his indisputable talent as an avant-garde storyteller, Kubrick accomplishes a level of formal perfection in 2001: A Space Odyssey that so few artists have ever come close to, boldly reaching out to touch the infinite, and revealing a glimpse of its sublime wonder as it reaches back to us.

2001: A Space Odyssey is currently streaming on SBS on Demand, and is available to rent or buy on Apple TV, YouTube, and Amazon Video.

2 thoughts on “2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)”