Copyright Ed Ruscha 2008 published by Steidl

I have been aware of Ed Rucha’s self-published photographic books for many, many years, but due to very small production runs and subsequent rarity, these books have been very elusive. It was a pleasure to find this retrospective catalog providing a broad selection of the interior images from his sixteen photobooks published between 1963 and 1972 and his last collaborative book published in 1978.

It is difficult to be artistically creative in Southern California without hearing about Ed Ruscha, whose studio is in, as well as primary subject is Los Angeles. Over the years, his photobooks sometimes took on mythical proportions, as they were actively discussed and referenced, recalling lectures in the early 1980’s at CalArts (Ruscha attended in 1956), but rarely seen in their entirety.

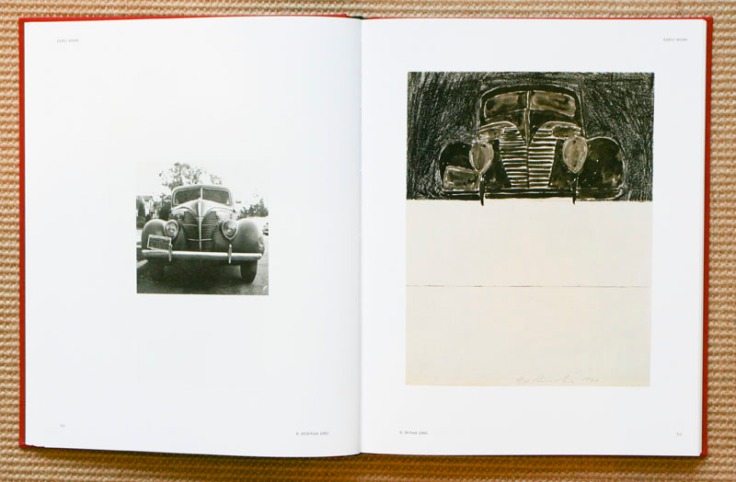

Although primarily known for his lithographic prints and paintings, his oeuvre also includes these seventeen photographic books, although the interior photographs were rarely, if ever, exhibited as singular photographs. If Ruscha found an appealing graphic element in photographs, it was synthesized into a lithograph print or painting. For Ruscha, the individual photograph was something required to create another object, the photobook. It is remarkable that an artist who’s photographic books have influenced so many photographers, especially urban landscapers, has only until recently had his photographs from his “hobby” collectively published in a retrospective. What creates even more interest is the marked up contact sheets and his unpublished but related photographs.

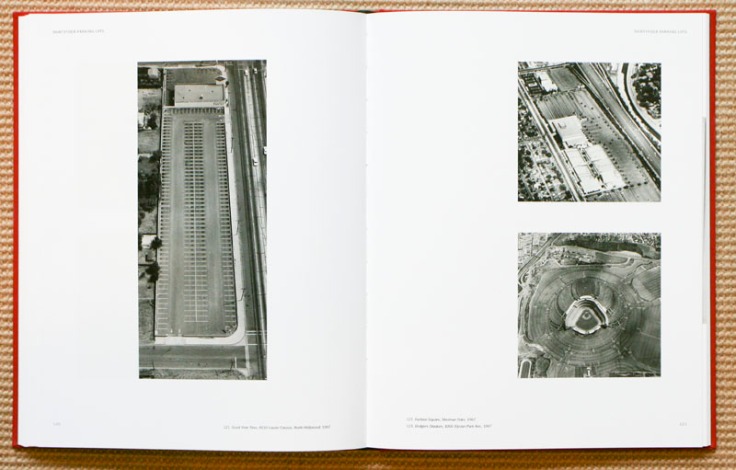

This book provides a wonderful sampling form the various Ruscha photobook projects, including; Twentysix Gasoline Stations, Sunset Strip, Some Los Angles Apartments, Thirtyfour Parking Lots, Nine Swimming Pools, Babycakes, Real Estate Opportunities, Dutch Details, Records and Colored People.

As noted in Rowell’s introduction, “Ruscha produced sixteen photographic books, publishing most of them himself, twelve devoted to landscape or still live motifs, and the remaining four may be loosely described as records of events. Each book in the former group was conceived as a repertory of prosaic subjects; gasoline stations, apartment homes, parking lots, cakes or palm trees. The majority (although not all) of the photographs were taken by Ruscha, in, according to him, the most neutral or “factual” manner possible.”

Ruscha has remarked, “Actually what I was after was no-style or a statement with a no-style” and “My interest in facts is central to my work, not that you’ll find factual information in my work”.

Ruscha was attempting to make non-esthetic documentary photographs and whose photographic books are an acknowledged historical influence on many of the exhibiting photographers in New Topographics exhibition at the George Eastman House in the 1975. Interestingly, Ruscha was not included in that pivotal exhibition. The “New Topographics” German photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher later assimilated the “Ruscha no-style” into what has become a Düsseldorf style, not only for themselves, but Thomas Struth, Thomas Ruff, Andreas Gurksy, Thomas Demand, Candida Hofer and others who themselves fell under the Becher’s influence at Kunstakademie. They were influenced by Ruscha’s enigmatic pictorial potential and cool aesthetic of the book’s urban landscapes.

In the introduction to the recent Steidl photobook New Topograhics, Britt Salvesen writes of Ruscha’s influence:

Bypassing traditions of singularity, fine printing and expressive layout in his deadpan inventories of everyday buildings and structures, Ruscha presented particular challenges (and opportunities) to those working in the context of fine-art photography. For the New Topographics artists, he became a polarizing figure with regard to the related issues of craft and irony. For some, his work affirmed their own instincts. (Lewis) Balz remembers discovering “photography degree zero” when he located Twentysix Gasoline Stations, Some Los Angeles Apartments and Sunset Strip at the SF Art Institute library in 1967.

(Steven) Shore likewise acknowledges that “Rushca’s work may have caused irritation in some parts of the art world, but for me and my friends his books were a delight.” (Robert) Adams and (Nicholas) Nixon, considering the question now, take a middle ground position; for Adams, Ruscha is “clever, sometimes funny”, while for Nixon, the work seemed like a “better idea than a thing”. John Scott reached a similar conclusion, and he provided (William) Jenkins with the assertion, quoted in the catalog, that Ruschas’s pictures “are not statements about the world through art, they are statements about art though the world.”

Ruscha’s photographs were the first to seriality document a subject, such that a singular image may not hold you attention, but a series of veru like subjects draws your interest, at a minimum to compare and to contrast, searching for similarities and differences. Ruscha has acknowledged his interest in breaking up his painting process into stages, thus the seriality of his photographic books reflects a similar systematic approach to photographing his subjects.

Ruscha has also acknowledged Marcel Duchamp as a strong influence with regard to “found objects,” that word’s “like a found object, (it) can be an unimportant word that becomes important when he repeats it to himself. Similarly, his photographic books entered his consciousness as catchphrases that gave him titles to turn into books.” That the “title came first, then to find or collect his subject matter”.

Ruscha influence extends to his selection of subjects, that as Rowell notes they would be “mundane, consisting of commercial or industrial architecture or commonplace objects, chosen for their inherent lack of artistic value” and that the “photography would be quick, casual and unprofessional”. For a skilled artist to attempt to create an “unprofessional” appearing photograph is to incorporate a carefully conceived and executed design element that would hopefully appear that it was created unprofessionally.

Meanwhile, his photobooks are noted to be rigorously designed, laid out and printed, reflecting more thought and deliberation. Such that Various Small Fires has “every photograph is reproduced in the same square format and placed on a right hand page”. Again, what can be argued as to Duchampian like contradictions, as in the previous mentioned book has fifteen images of something related to fire, but the last photograph is a place setting with a glass of milk, for which Ruscha states, “Milk seemed to make the book more interesting and gave it some cohesion.”

Roscha, in developing his conceptual framework, could also develop his photobooks in collaborations with writers, artists and other photographers (Art Alanis, Patrick Blackwell), who may in fact take the photographs. He subsequently would hire photographers to complete his projects, taking of the role of director, somewhat akin to the practice of Wall or Crewdson today.

As Rowell’s essay details, Roscha has influenced many artists, including Bruce Nauman, Robert Smithson, Cindy Sherman by his commonplace subject matter, neutral presentation, nonexpressive content and casual framing. Mel Bochner, Dan Graham, Douglas Huebler, and Sol LeWitt for his serial logic, as the photobooks true subject more so than the images.

From a photographic historical perspective, this is a book worth considering. It is the published catalog from Ed Ruscha’s 2006 exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

by Douglas Stockdale

Nice review. Thanks for sharing!

If you are interested, Ruscha’s “Real Estate Opportunities” from 1970 is up for auction.

http://cgi.ebay.com/ws/eBayISAPI.dll?ViewItem&item=260774372989

Do you have any new letter? I’d like to receive posts from Photobook Journal

Hello Claudia, Please provide your email address and we can sign you up. Otherwise send an email to editor@photobookjournal.com and request a free subscription. Cheers!