This summer, I was finally able to return to Italy for the first time since 2019. It was, of course, fantastic to be back and soaking up the atmosphere again. It was also the last funded research trip of my AHRC fellowship, and I wanted to make the most of it by visiting some lesser-known areas that I had not seen before.

One of my goals for this year is to learn a bit more about the Etruscan ports on the east coast of Italy. The ports of the west coast – like Gravisca and Pyrgi – are pretty well-known, and understandably. The art, architecture and inscriptions from those areas (especially the Pyrgi tablets) are completely amazing, and the materials are mainly kept in frequently visited museums in and around Rome and Naples. But the ports of the east – like Adria and Spina – are often forgotten, despite their roles in the connectivity of the Etruscan world.

The treasures unearthed at Spina are kept in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Ferrara – housed in a nice villa with a shady garden, and well worth a visit. Spina was only discovered in the 1920s, and most of it was excavated in the second half of the twentieth century. The museum’s party piece is the room with two entire wooden boats, each made from a single tree-trunk. These are extremely hard to photograph in person because of their size, but you can see what they look like on this link.

The museum is also filled with Greek vases, imported from Athens and other areas of Greece to meet the lively Etruscan export market. Most of the excavations are from the necropolis, and many of these vessels were buried with their owners as indicators of their social status.

This was a very rich site, with a huge amount of what I can only call ‘bling’ – including some of the chunkiest amber necklaces I’ve ever seen.

There is also a wealth of inscribed materials, mostly scratched on ceramics. Quite a high proportion of the names inscribed on the vessels from the necropolis show evidence of the immigration and mobility that made Spina so important. Greek and Italic names are mixed with Etruscan ones, often within the same person’s name. I quite like one from the third century BCE which is thought to read ‘P(l)ati’ in the Etruscan alphabet (right-to-left) and ‘Bla’ in the Greek alphabet (left-to-right) – possibly, the caption suggests, the owner was writing two versions of the same name, Platios (a name of Messapic origin from Apulia, in the south of Italy, which comes up in lots of different regions).

The excavations from Adria are kept in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Adria, which is two train rides away from Bologna, where we were staying. It’s a beautifully laid-out museum, despite its isolated spot. (And possibly the only museum I’ve been to in Italy that had a children’s playground?)

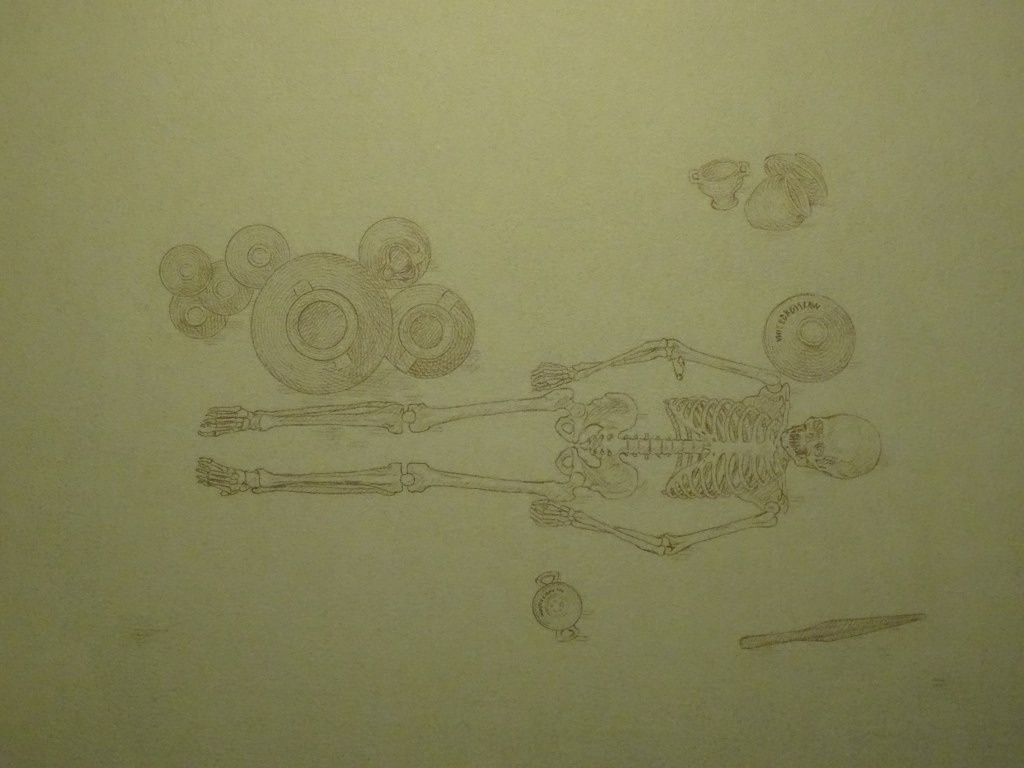

A great deal of the material from Adria is also from the necropolis. The site was active for much longer than Spina, well into the Roman period, and like Spina it was an active and wealthy port city. The display goes grave by grave, explaining to the viewer what was in each tomb, how the body was laid out, and who the deceased was.

One set of grave goods that stood out to me were those of a man called Verkantu, probably originally from a Celtic-speaking area judging by his name and the bronze fibula he was wearing, but a fully signed-up member of the Etruscan elite of Adria who was buried with a typical banqueting set and lots of Etruscan inscriptions. He had far more objects inscribed with his name than anyone else from Spina, and I feel intrigued about why having so many inscribed objects was important to him or his family.

Because Adria was active into the Roman period, they also had a good collection of Roman gravestones from the late Republican and Early Imperial period – showing just how much burial practices changed over this period.

I also really admired some of the creative ways they had displayed the Roman material that people might otherwise not give much thought – like this wonderful display of Roman glassware, really showing off the range of colours and styles.

The material at these museums is so rich – both in the sense of being historically important and the sense of being from a wealthy society. This was primarily a fact-finding mission for me, and I have a lot more thinking to do about everything I saw. But after some more detailed research I am hoping to work these sites into my discussions of language contact in port cities in Italy, and compare them to the better-known ports of the west.

Leave a comment