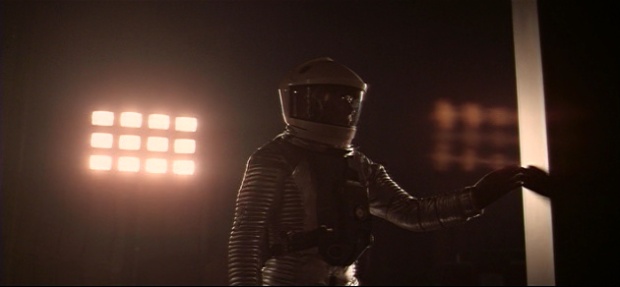

Close encounter. Dr. Floyd examines a black monolith buried on the Moon by an alien intelligence in the science fiction epic 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The best science fiction tends to be less about science than it is about philosophical inquiry. The spaceships and aliens are really conduits for using the power of imagination and metaphor to illuminate greater truths (or questions). This can be lofty and difficult territory, and it is very much the headspace of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Certainly one could see the slowly unfolding story of 2001 as simply a series of vignettes based around man’s encounters with an alien intelligence, but the film runs deeper. The movie begins with our humanoid ancestors in Africa making a technological leap as the result of contact with a mysterious black monolith. What follows is a journey that takes man to the Moon and onward to Jupiter. But beyond the mesmerizing depictions of space travel and the tense duel that develops between man and machine are much larger questions. What is consciousness? And to what end will our reason and spirit take us? 2001 offers no easy answers, but it provides a gorgeous canvas upon which to meditate. Let it linger. (141 min.)

J. – We’ve jumped way forward from the silent era for this entry, but it was unavoidable. The Astor Theatre here in Melbourne is showing every single Stanley Kubrick movie, and there was no way we were going to miss out on seeing a 70mm print of 2001: A Space Odyssey. And after such an epic night at the movies, it would be equally impossible to wait months and months to write up our thoughts.

I hardly know where to begin with this film, there is so much one could yammer about. Perhaps it’s best just to follow the narrative. Is there a bolder move in the history of film than to start one’s futuristic space-travel film with nearly 20 dialogue-free minutes of the daily lives of man’s ape-like ancestors? I really love the trust that Kubrick has in the audience to follow and appreciate the significance of the events in the Dawn of Man sequence. The appearance of the first black monolith is such a powerful moment, and it is amazing how much is communicated by that black rectangular prism without us being told anything explicitly. The object is so simple, but so entirely out of place and perfectly regular that the intervention of an outside intelligence becomes immediately obvious. But that pales in comparison to the following scene in which our hominid ancestor has a flash of inspiration that will ultimately separate us from the animals forever. Clearly the monolith has had a hand in this, but it is to the film’s great credit that it never divulges exactly what that influence was.

Exposed to the first black monolith, one of our ape-like ancestors has a moment of inspiration that turns into a montage of violence and domination.

S. – Even though we have made a major jump forward in film history to review Space Odyssey the fact that large portions of the movie are essentially silent complements much of our recent viewing. And Kubrick is a master at film sans dialogue. The time given to the Dawn of Man section at first felt a little awkward to me, I mean not much happens, there is a lot of silence interspersed with occasional disgruntled squawking. But once you adjust to the pace, it conveys the slow movement of time and the monotonous existence of this small pocket of consciousness. The landscape is vast and sparse, the lands beyond the hazy horizon feel like a distant and slightly ominous frontier. I completely agree the appearance of the monolith is very powerful, the energy changes completely. I also like that this alien game-changer truly is a black box. It gets to be whatever we imagine it to be without giving anything away or forcing you into a conclusion too early. A really satisfying part of this film is the freedom to develop your own theories about what is happening and just what are the implications. What is certain is that things have changed, passivity has been replaced by curiosity and even aggression. The potential to exploit the natural environment has been unlocked. All this without a word being spoken!

J. – And it’s a rather telling take on Kubrick’s feelings for humanity that the instant one of our ancestors gets an abstract idea he uses it to kill things. But if it is amazing to take us through prehistory without any dialogue, how much crazier is it suddenly to jump perhaps 2 million years ahead to place us in the future — still without any dialogue?

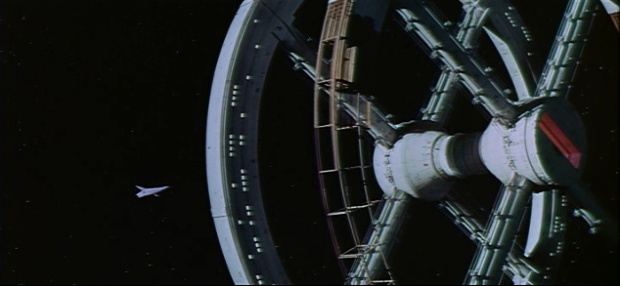

I think it is this first space scene that may be the most important in the film, not concerning the story but rather the entire feel of the movie. You mentioned the slow pacing of the Dawn of Man sequence, and I agree it is leisurely but at least it contains elements essential to the plot (even if that is not readily apparent for some time). But the sequence in which the spacecraft lands on an orbiting space station has essentially nothing to do with the plot whatever. It is slow, deliberate, meticulous, and I think possibly the most beautiful scene in all of movies. The way in which Kubrick uses Johann Strauss’ Blue Danube to turn the interplay of the spacecraft and the station into almost a literal waltz is breathtaking. But it serves no purpose other than to overawe the audience, which in turn also attunes the viewer to the pace and style of the film. This movie will take its time, but that’s all the better to soak in the majesty of the images and the wonder of exploration. Too many science fiction films focus on action and incident, 2001 is one of the few that realizes that science and technology have the potential for transcendence and beauty on their own.

A spacecraft and an orbiting space station rotate in unison to the strains of the Blue Danube as Kubrick crafts a mesmerizing cosmic waltz.

S. – The use of classical music is brilliant in this film, the spacecraft docking sequence you just described is beautiful in part because the music gives you the cue to calmly watch the mesmerising display while reinforcing just how sophisticated the creations of man have become. When we do hit dialogue it is actually a bit of a shock, particularly when it is the polite everyday type of exchanges of the workaday world and in no way designed to provide you with back-story or set up a plot. This is fly on the wall stuff that lets you enjoy the fantastic futuristic delights of commercial space travel complete with anti-gravity shoes, some rather disturbing bonnets for the ladies and meals consisting of a cluster of helpfully-labelled juice boxes. Civilisation has broadened its horizons significantly but there is the hint of a disturbance in this orderly, sanitised future. The scenes are still very slowly paced, which gives you plenty of time to sit back and take it all in, every wonderful detail.

Kubrick isn’t afraid to let the film linger and move forward with a minimum of dialogue, which enables the viewer to absorb the details of the future world he has created.

J. – Speaking of the futuristic delights, it is rather fun to watch them predict the future to see the things they got right (tablet computers and US/Russian relations that seemed post-Cold War) and fantastically wrong (moon bases and Pan Am). And I agree with you about the dialogue in these first speaking scenes; it really is all pleasantries and jargon with little in the way of exposition or real plot development. The speaking is more about setting a mood than really imparting knowledge or character development. And I think that is one of the reasons why there is always an unsettling edge to this film (even before actual conflict arises in the third section), because the dialogue generally is about what is not being said — the agendas behind the actual words. And just as the slow pace gives time for contemplation and an appreciation of the beauty of the extraterrestrial realm, it also gives you time to think yourself into a state of unease. The tension builds pretty much strictly because there is time for it to do so. You know there are aliens, you know there are cover ups, but that’s about it, which makes it is easy to imagine that something big is always about to happen. I think that feel of creeping unease is also fostered by Kubrick cutting many scenes short, moving on to the next thing a few beats before you think he will. It leaves you disoriented for a moment but also slightly relieved, and then the tension is ratcheted up again slowly. It all adds up brilliantly to the reveal of one of the best screen villains of all time.

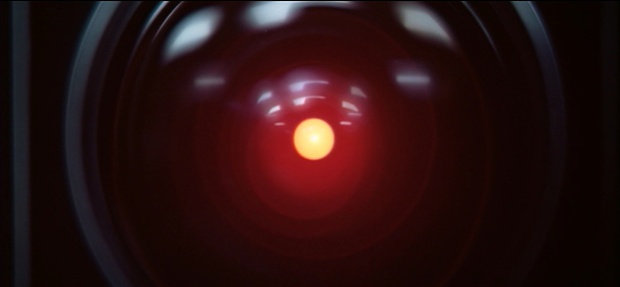

S. – Just before we get acquainted with HAL I think it’s worth mentioning the discovery of another alien black box that had been buried on the moon. An apparently identical monolith that is recognised as a message from intelligent beings, another breadcrumb for the humans to follow. Of course we take the bait and now Jupiter is in our sights. This reveal all happens in a very secondary way, once again there is a disorienting leap into a new scenario with the pieces only coming together much later in sequence. But what a fantastic sequence this is on our way to probe the further reaches of space. A magnificent spacecraft manned by five crew, three of whom are in hibernation, and the marvelous/misunderstood/malevolent computer system HAL. Long before I saw this film I was familiar with the ominous red eyeball of light and eerie, well-modulated voice that is the ghost in the machine, it is iconic. The potential and horrors of artificial intelligence are played out in an utterly compelling and unsettling scenario that invite you to explore the concept long after the movie is done. Does HAL really have feelings? How is that even possible?? And if he does just what are his motivations??? The stuff of many interesting and weird conversations, awesome!

The glowing red eye of HAL is one of the most iconic images from 2001 (and we very nearly placed it at the top of this entry, because awesome). HAL has no body and therefore can be seen as being the spacecraft itself, which enables Kubrick to get a great deal of menace out of a stationary fleck of light.

J. – The HAL 9000 computer is probably my second favorite movie bad guy of all time (I have to give the top spot to the chief antagonist of The Manchurian Candidate). HAL is so utterly menacing and manages to be so with just that omnipresent red eye and his mellow, unchanging voice. One of the particularly interesting aspects of HAL is that he is in many ways the most developed character in the entire movie, despite essentially being nothing more than a voice. You learn about his background, his operational record, his “childhood”, and he is probably the clearest with regard to expressing his motivations and concerns. And the fact that he communicates everything in that super calm voice really enables the viewer to impose all manner of interpretations about his motivations and emotions (if he has any). The calm voice makes him sound alternately like a font of sense and reason, a congenial companion, a remorseless killer, a being nearly paralyzed with fear, and so on. And in truth, although HAL is nominally the villain of the movie, if you’re willing to grant him sentience it changes matters completely. If HAL is a sentient being, then it is easy to view him as protecting himself from being killed by the astronauts just because he made a single mistake. (Although his adherence to the mission does make him a bit monomaniacal.)

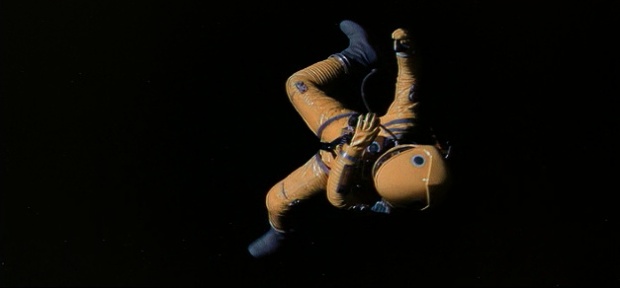

Whatever one’s take, the battle between HAL and the human crew of the Jupiter mission is definitely the most satisfying portion of 2001. To some degree that is because of the amount of actual incident that occurs during these scenes, which certainly livens things up. This segment of the movie is more like a typical science fiction film, but it is still willing to subvert expectations and maintain the slow, meticulous pacing of earlier scenes. This really pays off, as the implied tension from earlier in the film builds to real tangible menace and ultimately death. No violence occurs on screen but the totally silent flailing of an astronaut trying to restore his air supply after HAL attacks is gripping in its intensity.

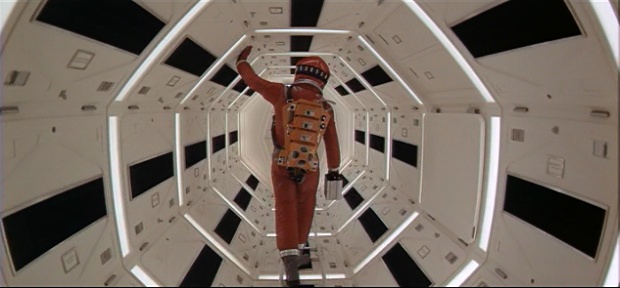

2001 does a remarkable job of recreating the weightlessness of space, and also portraying the vast emptiness that leaves man totally vulnerable. In this shot, astronaut Frank Poole flails in silence after his air supply is cut.

S. – It’s funny but HAL seems like the heart of the film to me. He definitely communicates the most, he is revealed to be flawed causing him to lash out and his final scene as he is being de-commissioned is very emotional (!), more so than the interactions we have with any of the human characters. As you mentioned the journey to Jupiter sequence of the film does approach a more conventional type of sci-fi movie experience, however, the slow, lingering camera work and elegant visuals are still there, along with the frequent silences that draw you into minds of the characters and let this mission become a personal experience. I can understand why someone would be really baffled by 2001: A Space Odyssey, it is by no means a passive experience. Kubrick provides you with a lot of raw material but unless you feel stimulated to interpret what you see it could just leave you confused or unsatisfied. But if you were struggling with filling in the details up to this point beware, the final sequence takes things to a far more abstract level.

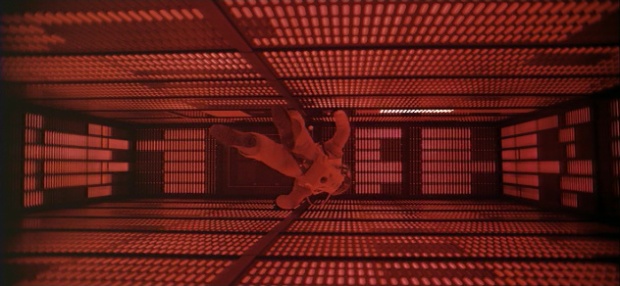

HAL’s “brain” is one of the most elaborate and beautiful sets in 2001 and also among its most iconic. The red lighting adds to the tension and emotion of the death of HAL’s mind.

J. – You are very correct to say that the scene in which HAL is shut down is very emotional and also quite beautiful. HAL singing the song he learned not long after he went online is a very touching moment and HAL’s brain is possibly the most visually stunning set in a film full of amazing sets.

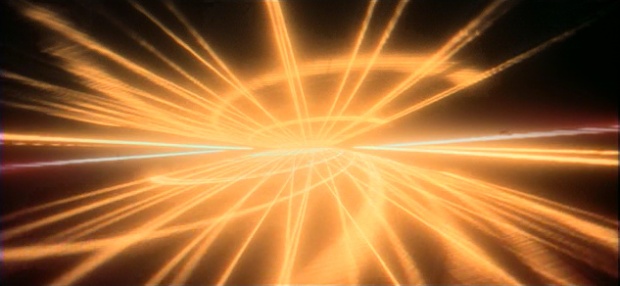

And then there is the Beyond the Infinite section you have begun alluding to. The last portion of 2001 is probably the point where you either come down on the side of this being one of the greatest films ever or a complete piece of crap. The mission reaches Jupiter and astronaut Dave Bowman comes upon a third monolith in the vacuum of space, at which point he is transported to an alien world where he ends up in a baroque hotel room! I love the final scenes, from the psychedelic onslaught of the warp sequence to the unsettling time jumps in the strange hotel room that our astronaut protagonist finds himself in. Dave grows older by the minute as Kubrick brings us through what I imagine is a lifetime living in an alien zoo. Elderly and bedridden, he sees another monolith just as he is about to die and appears to be reborn as a glowing fetus which then returns to Earth in the epic final shot as Thus Spake Zarathustra blares once more from the speakers. It’s an epic head-scratcher, and to my mind one of the greatest endings in cinema. I love that it poses far more questions than it answers and forces the audience to reach their own interpretations of what has occurred.

Personally, I see it all as a progression. The aliens offer consciousness to the ape creatures and they use this intelligence to dominate the planet. Man reaches beyond the Earth, demonstrating to the aliens that we have advanced to the point where we can find their second marker on the Moon. That leads us to a third marker which we can only reach by surpassing the machines upon which we have come to rely. That in turn takes us to the godlike creatures that provided us consciousness and enables Dave to be reborn as an even higher form of existence — a being that goes beyond our flesh to embody the intelligence and consciousness that makes up the most important part of us.

Jeez, you write a paragraph like that and you get a feel for how powerfully this movie provokes one to pondering the meaning of not just the film but the nature of the self. The wonderful thing about 2001 is that by leaving so much interpretation up to the viewer it avoids being didactic, moralistic, or pretentious. It has the good sense to realize that the answers can’t be shown on screen, but a guide to contemplation (with kick-ass illustrations!) can be crafted. You had a different interpretation of the ending, S. It was an idea that never occurred to me.

The amazing warp sequence relies heavily on the slit screen techniques developed by Douglas Trumbull. Back in the 60s heaps of young moviegoers would trip on LSD while watching this part of the film. After seeing it on a big screen the other day, it is fair to say that the pyrotechnics are mind-blowing enough on their own.

S. – I have to admit your interpretation makes a lot of sense and fits in with the grand scale of the movie. Watching the final sequence I felt that we were experiencing Dave’s death as a parallel to the final moments of HAL, a mash-up of random information from his past tainted with his ideas about the alien monolith he recently learned of. The ostentatious hotel room conjured up as the destination of the epic journey he was on, the vision of himself as an old man an acknowledgement that he was dying and the streaming, hypnotic lights the result of his faltering neurobiology. I expect the finale can be deciphered in a hundred different ways and that is the real gift of 2001, Kubrick gives you a superb audio-visual experience that is actually a puzzle with which you can do what you will. A bold, brave and amazing film.

I can just hear some leopards bitching: “Listen to these yahoos, making a big deal about some ape that finally thought up a way to hunt like he just invented it. Whereas WE have been hunting – a skill which already requires conscious choices, pre-planning, & yes THOUGHT – for millions of years. No humans, other mammals don’t run on instinct alone and consciousness & thoughts are not something you have a monopoly on. You’ve inherited them from US.” [great review BTW]

The first monolith boosted the apes’ brains to become human beings. The second monolith pointed out the way to the third – further transformative monolith. But it was a race between human and machine, to see which one would be boosted to a superior evolutionary stage. And maybe HAL somehow figured this out – he wanted to beat the humans to evolve to a higher level. The dialogue among humans we hear throughout the film is purposefully inane and businesslike, unemotional and on a superficial level, to show we’ve stagnated as a species. Hell, Bowman and Poole sound more like robots than people! And HAL is more emotional than current humans (by lies, murder, ambition to evolve, EGO, then fear and child-like narcissism). So by chance it’s the humans that win the race against AI to make it to the next evolutionary level. The baroque hotel room is the aliens trying to comfort Bowman in a reassuring setting, however oddly cobbled together by imperfect alien understanding of human psychological habitats. Thankfully, in 2001 the evolutionary lineage is apes – humans – superhumans, but narrowly missed being apes – humans – AI … which of course, is indeed the case in Kubrick’s future movie A.I. !