[You can now hear this post as an audio podcast via this link. It is also available in video form here.]

[You can now hear this post as an audio podcast via this link. It is also available in video form here.]

There are many baffling (let’s go with the critical consensus and call them “enigmatic”) aspects of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, and it’s going to take a lot more than a rapidly knocked-off blog entry to solve them. Like the blank, featureless monolith at its core, its mysteries cannot be definitively resolved no matter how hard you stare at them. Once you come to terms with that, you can enjoy the movie without it seeming like a space opera that fails to deliver the requisite thrills and resolutions. In some ways, disorientation is one of the film’s central motifs, whether it is created by the vast narrative ellipses, emotionally pale characters or the ambiguous, sometimes abstract spaces it depicts. Watching it again, I noticed numerous shots where Kubrick imposes a strict horizontality on the mise-en-scene. Let me explain what I mean.

2001 is about progress, the development of technologies that precipitate paradigm shifts in human life and relationships. The opening section famously shows the shift by apes from hunted, cowering scavengers into weapon-wielding territorial carnivores. The apes hold their bodies low to the ground, hunching their shoulders and scraping around in the dirt for food. One day, a large black monolith appears in their midst. Fearful at first, they seem to subject themselves in awe to the inert and inscrutable block. In return, it appears to stimulate a major evolutionary leap, inspiring one ape to to notice that the bone of a dead animal can be used to smash the bones of living creatures, providing plentiful meat, but also assisting with the subjugation of rival tribes. They become hunter-clobberers. All the apes are played by actors in suits and heavy prosthetics, except for one or two real chimpanzees to differentiate them from the new breed of enlightened beasts that will presumably evolve into homo sapiens. It will be those who dare to stand upright who will advance. Oh, and those who dare to take up arms and beat the crap out of something.

2001 is about progress, the development of technologies that precipitate paradigm shifts in human life and relationships. The opening section famously shows the shift by apes from hunted, cowering scavengers into weapon-wielding territorial carnivores. The apes hold their bodies low to the ground, hunching their shoulders and scraping around in the dirt for food. One day, a large black monolith appears in their midst. Fearful at first, they seem to subject themselves in awe to the inert and inscrutable block. In return, it appears to stimulate a major evolutionary leap, inspiring one ape to to notice that the bone of a dead animal can be used to smash the bones of living creatures, providing plentiful meat, but also assisting with the subjugation of rival tribes. They become hunter-clobberers. All the apes are played by actors in suits and heavy prosthetics, except for one or two real chimpanzees to differentiate them from the new breed of enlightened beasts that will presumably evolve into homo sapiens. It will be those who dare to stand upright who will advance. Oh, and those who dare to take up arms and beat the crap out of something.

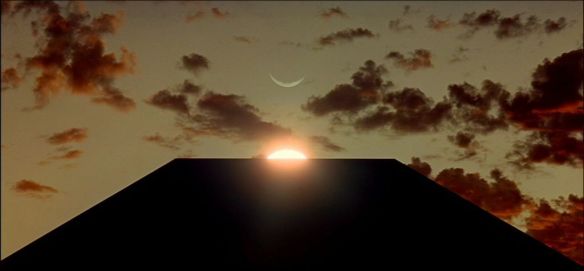

If the monolith’s appearance is significant in triggering the paradigm shifts that enable the evolution of humankind (and it is not certain that this is the case), then its power is signified by its presence at moments of cosmic order. It completes a pattern, becoming aligned with planets and moons and unlocking (?), sign-posting (?) or simply observing (?) a powerful coincidence of objects. The emergence of patterns becomes important as a graphic motif throughout the film. For the apes, the monolith represents a startling interruption of routine by straight lines and symmetry. From that point on, humans assume a new relationship with objects and tools. The match-cut which elides millions of years of history makes plain that this shift in perception is all you need to know about humans to understand how they went from picking fleas off each others’ backs to putting a space station into orbit.

If the monolith’s appearance is significant in triggering the paradigm shifts that enable the evolution of humankind (and it is not certain that this is the case), then its power is signified by its presence at moments of cosmic order. It completes a pattern, becoming aligned with planets and moons and unlocking (?), sign-posting (?) or simply observing (?) a powerful coincidence of objects. The emergence of patterns becomes important as a graphic motif throughout the film. For the apes, the monolith represents a startling interruption of routine by straight lines and symmetry. From that point on, humans assume a new relationship with objects and tools. The match-cut which elides millions of years of history makes plain that this shift in perception is all you need to know about humans to understand how they went from picking fleas off each others’ backs to putting a space station into orbit.

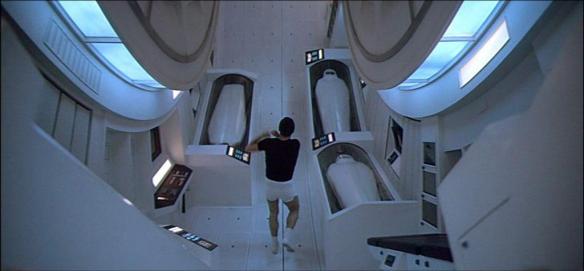

In zero gravity, it becomes a moot point which way is up or down, with only the distantial relationships between objects making any sense. Hence the blissful docking of spacecraft which have mastered the dance and found a common orientation. In 2001 interplanetary travel is not just for those with the “right stuff”, but rather a smooth, Club Class jaunt; all of the troubles of weightlessness have been circumvented by the innovations of various corporations whose logos pepper the onboard instruments. At various points, the set’s spatial clarity can be upset by a change of direction, a remix of the lines of action you thought were in play. An air hostess steps carefully down a corridor before turning and walking up the walls; later, Frank Poole jogs around the interior of the ship, seeming, from one perspective, to be running perpendicular to the floor. The next shot gives us a different point of view, as if to remind us that the orientations suggested by these interiors are denials of the actual relations between objects loosed from any gravitational pull.

In zero gravity, it becomes a moot point which way is up or down, with only the distantial relationships between objects making any sense. Hence the blissful docking of spacecraft which have mastered the dance and found a common orientation. In 2001 interplanetary travel is not just for those with the “right stuff”, but rather a smooth, Club Class jaunt; all of the troubles of weightlessness have been circumvented by the innovations of various corporations whose logos pepper the onboard instruments. At various points, the set’s spatial clarity can be upset by a change of direction, a remix of the lines of action you thought were in play. An air hostess steps carefully down a corridor before turning and walking up the walls; later, Frank Poole jogs around the interior of the ship, seeming, from one perspective, to be running perpendicular to the floor. The next shot gives us a different point of view, as if to remind us that the orientations suggested by these interiors are denials of the actual relations between objects loosed from any gravitational pull.

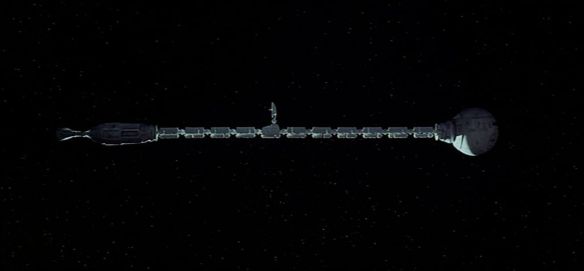

Kubrick’s compositions in interior shots are decidedly horizontal for the most part. The spacecraft, cockpits, docking bays and patterned lines cumulatively depict the imposition of order, straightness and an anthropocentric levelling-out of the inconceivable, directionless emptiness of outer space:

Kubrick’s compositions in interior shots are decidedly horizontal for the most part. The spacecraft, cockpits, docking bays and patterned lines cumulatively depict the imposition of order, straightness and an anthropocentric levelling-out of the inconceivable, directionless emptiness of outer space:

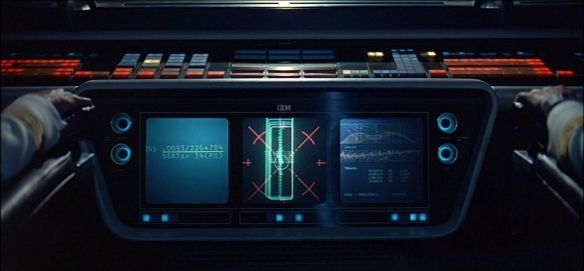

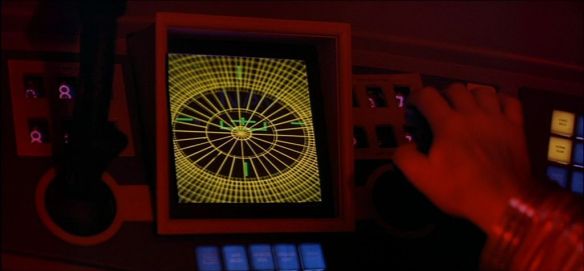

The technologised subjection of space to measurement, alignment and re-orientation is also seen in the focus on the navigation screens which show wireframe drawings of spacecraft on rigid grids that segment and demarcate the blackness. This equipment enables pilots to bring floating craft into a more co-ordinated and stable state:

The technologised subjection of space to measurement, alignment and re-orientation is also seen in the focus on the navigation screens which show wireframe drawings of spacecraft on rigid grids that segment and demarcate the blackness. This equipment enables pilots to bring floating craft into a more co-ordinated and stable state:

There are ecstatic moments when clarity and alignment occur, as in the quasi-mystical lining-up of planets in the opening salvo, as if their rare order switches on the film with a cosmic, curtain-raising overture. There are threats to humans’ attempts at universal horizontality. The monolith inserts a resolute vertical into proceedings, and its apparently deliberate placement on the moon is a shocking discovery to a species who had previously believed themselves to be the only beings capable of the careful positioning of things.

There are ecstatic moments when clarity and alignment occur, as in the quasi-mystical lining-up of planets in the opening salvo, as if their rare order switches on the film with a cosmic, curtain-raising overture. There are threats to humans’ attempts at universal horizontality. The monolith inserts a resolute vertical into proceedings, and its apparently deliberate placement on the moon is a shocking discovery to a species who had previously believed themselves to be the only beings capable of the careful positioning of things.

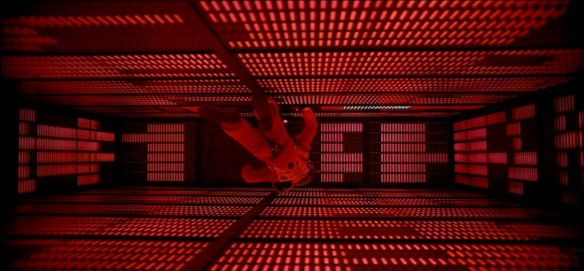

Now, although I’ve offered one way of reading 2001 as a depiction of human endeavour as the taming of space and distance, and I’ve done this just by looking at the arrangment of certain shots, this is not the only way to read the film. It would be even more difficult to pin down an editorial attitude to questions of technology coming from Kubrick or Arthur C. Clarke. There are plenty of moments of awed contemplation as the camera lingers over its spacecraft, ejecting people from the frame and decentring dialogue to an indistinct babble of small-talk in several scenes. Elsewhere, the beautiful machines turn menacing, either by their sheer scale or under the control of the artificially intelligent computer HAL, whose impermeable logic cannot be reasoned with once he decides on his own course of action. Is this late insertion of a lethally flawed computer supposed to undercut the preceding tech-fetishism? It is difficult to say, since the final shots are impossible to reduce to a closing comment (a reading of Clarke’s story The Sentinel will provide some clues, but the film’s version is not easily assimilable with it in many respects). The transformation of Dave Bowman into a gargantuan “starchild” (the film’s most dramatic reconfiguration of notions of relative scale) overlooking the surface of Jupiter is an evolutionary leap of which we cannot conceive. It moves humankind beyond a trifling interaction with levers, switches and big mechanical toys into a new arena of unbounded space where the rules of up, down, forward and back no longer need to apply. Maybe. That’s the brilliance of 2001. It defies explanation, but manages to give the impression that it is not a surreal refusal of sense, but a distant, advanced form of representation that will only be interpretable the next time a monolith appears to help with the next stage of consciousness.

Have you noticed how the lack of a traditional narrative in 2001 seems to make some people incredibly angry?

Oh, I’ve known plenty of people who are happy to dismiss this film as an overblown, pretentious mess.

I’ve only seen it on the big screen once, and I have to say it’s a totally different experience. I know people say that about a lot of movies, but in this case I think it’s true, so maybe its detractors don’t really feel its power when they see it on a TV screen.

Watching it again, I was struck by how engaging it is. There are regular hints at a grand mystery to keep you interested, and although the narrative is not a traditional one, the recurrence of the monolith gives it some structure and forward drive – it’s wholly linear, so it shouldn’t be confusing in any way (except when it doesn’t give you all the information that you might be used to receiving).

Maybe it’s not the lack of narrative that annoys people, but that coupled with the lack of strong human characters for most of the running time.

Any idea what a shot length of this would be like? It’s been years since I’ve seen it, but I have faint re-collections of long(er than average) takes.

I think it is probably the lack of a resolutely ‘human’ narrative that really ticks people off (and perhaps also the fact that any kind of substitute ‘mimetic’ interest is repeatedly resisted by Kubrick’s emphasis on overwhelming scale and technological coldness).

Cinemetrics has two reviews of 2001, and the ASL averages at about 13.5 seconds. I’m surprised it was that long, though. Watching it again, it seems to have been cut much quicker than I’d remembered.

The human lack in 2001 is clearly deliberate, but I can see how it might switch some viewers off. I’m told that the feeling of utter insignificance is familiar to people who spend their lives working with the astonishing bigness of space (to paraphrase Douglas Adams).

Just noticed on Cinemetrics that the two counts for City lights give it an ASL of either 19.7 or 8.5. I’d side with Yuri Tsivian, who gives it the longer average, but I would have guessed it was somewhere in between the two. Luckily, nobody has to rely on my guesswork…

Indeed it does – Google failed me. I thought it might have been longer. ASLs are curious – over the last couple of days I have got 14.4 for Renoir’s ‘Boudu sauvé des eaux’ and 11.3 for Bresson’s ‘Un condamné à mort s’est échappé’ – both longer than expected. Interestingly, Renoir notes in a conversation with Bazin & Rossellini (S&S 28.1, 1958/9, 26-30) that ‘…for some reason, I’ve discovered by experience that my shots usually average out at about five or six metres each (16-20 feet), though I know it sounds a bit ridiculous to gauge things this way…’

I’d be inclined to side with Tsivian too about ‘City Lights’, but that’s a huge discrepancy…

Having looked again at the Tsivian entry on City Lights, I see that it is not the usual measurement of shot scales, but a “laugh count”. We’re showing it later this semester. I might try and measure the chuckles here, too…

There were a few definate laugh out loud moments in the screening today (I think the term LoL’s would be an appropriate acronym for academics to use in this area of study). Once when the monkeys went ape (lol) and beat the inferior monkeys with their bones, once when that poor astronaut flies out of control into space, possibly once when those weird looking cosmic cuboids form from beyond the infinite (although I think that was more of a giggle than a laugh out loud moment). Finally there was a definate LoL when the film ends after the floating foetus looks at earth. Thought the film was amazing though, I’m now going to ignore all advice and search deep into the internet for the exact meaning of everything in the film (not really).

Glad you liked it. I didn’t really “get” 2001 until I was able to see it on a big screen, when it made total sense. Not as a story, but as a spectacle. The themes of the film are bigger than us. It helps if the pictures are, too.

It’s such a sombre film at times that it helps to laugh. It think it’s dated pretty well for a 40 year-old, so there aren’t too many comic anachronisms.

There’s fun to be had in trying to explain what it all means, and the film is intelligent enough that it suggests that explanation might just be possible when you attain a certain level of consciousness, pretentious as that sounds. There are some links from this blog entry to some writings that attempt to explain it all definitively. This one is much better:

http://metaphilm.com/philm.php?id=449_0_2_0_M

These are a bit nuts:

http://www.visual-memory.co.uk/amk/doc/0041.html

If I had seen the film for the first time on a television (or I-phone!), instead of the big screen, it would not have had such an impact on me. In the very public context of a cinema or exhibition of some kind, the beginning two minutes of darkness make sense. I can imagine viewers skipping the first scene on their DVD versions, in the cinema we are forced to “watch”. Also interesting that the version we saw kept the “intermission” inter-title, at which point we all had a bit of a stretch!

Yeah, I guess the intermission is a holdover from the cinema release – with video you don’t need to be told when you’re allowed to take a breather. That said, the intermission isn’t really long enough to do much. Next time, I’ll get one of the porters to come round with choc ices.

When you have a film with lots of plot, you know what your job is – you have to remember the details and build them up into a comprehensible whole that allows you to make, say, value judgments about a character, or solve a mystery etc. What do you do in a film where the narrative is not the central focus, and there are moments where you just stop and stare?

That’s an open question. I’m not picking on you, Rob…

The ‘moments where you just stop and stare’ sound very ‘cinema of attractions’ to me. I think the ‘challenge’ of shifting concentration from narrative to mise-en-scène (or: the shot / pro-filmic environment) is pretty easy here – it’s not like Kubrick isn’t giving us anything to look at!

It’s definitely true that it’s easier to find spectacle in really big things, especially machines and monsters. It’s a lot harder to compensate for the narrative pull if you want the viewer to look at a herd of cows for nine minutes (to pluck one random example out of the air…). It’s still amazing that most of the special effects still stand up to inspection. To paraphrase my own research on this, the viewer’s gaze is a punishingly inquisitive one, and Kubrick really challenges you to recognise that those giant spacecraft are actually plastic miniatures. I didn’t notice that the whole of the sequence with the apes is shot in a studio with front projection screens until I read about it. Even now, it takes a few moments to work out where the join is. I don’t think it’s a problem that viewers try to decode the special effects and see through the tricks. That oscillation between suspension of disbelief and critical distance is common to all kinds of engagement with art.

‘Cinema of attractions’ was supposed to describe the relationship between sets of films as much as it ever was to do with the ways in which individual films depict moments of spectacle. It designated a mode of cinema where many films were placed together as a sequence of views rather than as an accretion of causally connected narrative details. Even Gunning himself suggested that the attractionist aesthetic was dispersed into popular cinema in action set-pieces and special effects sequences (he pointed at Lucas and Spielberg, as I recall), but narrative was so firmly established as the dominant paradigm that I’m not convinced that the comparison is valid. Nobody would sit and watch Kubrick’s spaceships for two hours if there was no narrative hook, no sense that the “odyssey” was heading somewhere or that these images meant something. There is thematic content in the way those lingering shots of machines exclude people, reduce them to minor details in a world where machines do most of the mechanical and symbolic work.

I must stop trying to answer my own questions. Sorry, I went off on one there!

Thanks for clarifying the distinction of a ‘cinema of attractions’ – it was in my head after reading Andrew’s new article in Cinephile, and I suppose I was thinking of it in very basic terms: “the cinema of attractions directly solicits spectator attention, inctiting visual curiosity, and supplying pleasure through an exciting spectacle – a unique event, whether fictional or documentary, that is of interest in itself” (Gunning, ‘Early Cinema: Space, Frame, Narrative’, 58).

It is interesting that Gunning refers to “the Spielberg-Lucas-Coppola cinema of effects”, but the spectacle Kubrick creates doesn’t rely nearly as much on direct narrative concerns (such as involvement with the plight of the characters) during the effects sequences as those directors do. There’s a sort of ‘purity’ to the attractions in ‘2001’ unusual in narrative cinema – at times, spectacle fully uproots the dominant framwork.

Also, pushing this slightly off-topic, I can’t help thinking that there’s always some sort of narrative hook within actions/shots that don’t immediately appear to have one. Take Tarr’s cows in ‘Sátántangó’: the herd enters the farmyard, begins to separate whilst plodding through, then disperses on reaching the field – the shot ends when they have reached their destination and the ‘action’ is over. The same goes for Kiarostami’s driftwood, dogs, ducks, etc. I always feel that these shots & events are heading somewhere, whether they ‘mean’ anything or not. Only those who are patient enough will find out, though…

Don’t get me started on those cows! One of my earliest blog posts was a slightly silly response to that opening shot from Satantango. I still don’t know what to do with it. If it was people milling about and then heading off somewhere, we’d presume, justifiably, that it was choreographed. I like to think there are dozens of takes in which the cows stood about for a bit, then maybe one of them took a dump and they wandered back into the barn or something. But that’s just me.

That shot wouldn’t have the same effect if it wasn’t at the beginning. That’s when you’re most acutely seeking direction and narrative information, waiting for some cues about what the film is about and where it will proceed. Handing that burden over to a bunch of cows is genius. I could as easily believe that that shot was completely unplanned as I could accept that the cows were being pulled along by hidden wires. The fact that it is cows sets up perfectly that ambivalence, and prepares you to seek significance in places where you might not usually expect it.

Do the cows reach a destination, or do they just leave the yard for an uncertain goal? Maybe they’re heading for Beverly Hills? It could just be a succinct depiction of the collapse of the farming commune. Whatever, it’s mesmerising because the duty of supplying the initial narrative information is delegated to dumb animals who don’t care what you sat down to watch.

I could go on and on and on about those cows.

So, is there always an expectation that a shot will “go somewhere”, i.e. that you are required to see it all and then assimilate it with the broader project of a particular film? That would suggest that narrative always exerts an influence and raises expectation, urging you to relate sequences of shots to one another as a matter of course.

Yes, you’re absolutely right that the shot is particularly effective because it takes place at the very beginning (hence, the most ‘open’ point) of the film – that’s probably far more significant than I thought. At that point, we are probably searching far more actively for a narrative hook to the action than we might be later on (when possibilities have narrowed and other things are on our mind). But I wonder whether it would also work at the beginning of one of the (twelve) chapters that divide the narrative as well – and what about similar ‘non-events’ that rupture the course of events later on, such as the (sublime) owl-zoom?

An interesting counterpart is the night-dawn-day opening of Reygadas’s ‘Stellet Licht’ – it’s a stunning shot, slipping us into the world of the film through the gradual rising of the sun (I wish we witnessed daybreak like that round these parts). In a way, though, it’s almost completely self-contained – absolutely nothing to do with plot or character is revealed, and Reygadas simply plays it in reverse at the end to signify closure (of the film) and continuation (of something beyond the film).

A thought about ‘going somewhere’ (although it doesn’t answer your question): I listened to a bit of Laura Mulvey’s commentary after watching Rossellini’s ‘Viaggio in Italia’ again the other night, and she describes the two driving shots at the beginning as opening the film with ‘pure movement’. It’s a very vague description, but this is how I think of shots like the ‘Kraftwerk on the M4’ windscreen-POV in Chris Petit’s ‘Radio On’ (easily the equal of Wenders’s 1970s road movies), and Irimiás & Petrina’s walk down the centre of the windswept street in ‘Sátántangó’. The interesting thing about these shots is that they do nothing but ‘go somewhere’, presenting pure dynamic motion (vehicle, camera, protagonists) so that anything else would surely feel superfluous.

Pingback: Brainstorm: The Medium is the Mess « Spectacular Attractions

The moment’s probably passed, but the subject of the ASL on City Lights came up on this thread. I’ve just rewatched the film, and I didn’t take a measurement of the ASL, but was struck by the shot during the boxing match that lasts for just over 80 seconds. That must skew the average a little…

Pingback: Screed for Speed « Spectacular Attractions

Pingback: New Look, Old Posts. « Spectacular Attractions

Pingback: The First Spectacular Attractions Podcast « Spectacular Attractions

Pingback: Essay: Time and Memory in La Jetée, 2001 and Solaris « Real Virtuality

I think Kubrick scholars and fans will enjoy my new book, Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey — How Patterns, Archetypes and Style Inform a Narrative. I explore Kubrick’s use of archetypal symbolism and patterns and offer new insights into his way of using music in 2001. it’s available in bookstores or may be ordered directly from us at Leonine Productions, 7 Spring St., Waverly, NY 14892.

http://blog.makezine.com/archive/2010/10/2001_monolith_action_figure.html

Wondered if you’d seen this yet, fairly amusing

Thanks, T. That’s awesome. “No points of articulation.” Genius. http://tinyurl.com/ykk7ey8

Pingback: Inception | Spectacular Attractions

Pingback: Spectacular Attractions Video Podcast #001 | Spectacular Attractions

Pingback: Spectacular Attractions Video Podcast #002 | Spectacular Attractions

Pingback: Gravity: The Weight of Water | Spectacular Attractions