Roman Frescoes

Fresco, an ancient mural painting technique, involves applying pigments to freshly laid lime plaster, allowing the colors to merge with the surface as the plaster sets, creating a durable and integral artwork.

In Roman architecture, frescoes served not only as decorative elements but also as practical solutions to the challenge of windowless and dimly lit interiors. By adorning walls with vibrant scenes and colorful motifs, frescoes illuminated rooms, creating an illusion of light and space and imparting a sense of airiness to otherwise enclosed spaces. These lively and dynamic paintings transformed the atmosphere of Roman interiors, infusing them with vitality, warmth, and visual interest, while also providing a glimpse into the artistic tastes, cultural values, and daily life of the ancient Romans.

The Roman Empire boasted a rich tradition of fresco artistry, with affluent homeowners and businesses adorning their walls with vibrant scenes and intricate designs. While much of this artistic heritage has been lost to time, special circumstances have preserved select examples for modern appreciation.

Among the most renowned are the wall paintings unearthed at Pompeii, Herculaneum, and nearby sites, offering a fascinating glimpse into the decorative tastes and lifestyle of the region’s elite before the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

These meticulously crafted frescoes reveal the opulence and sophistication of a wealthy seaside community, showcasing a diverse array of subjects ranging from mythological narratives and scenic landscapes to intricate architectural motifs and whimsical vignettes. As windows into the past, these evocative artworks provide invaluable insights into the daily lives, cultural preferences, and aesthetic sensibilities of ancient Roman society.

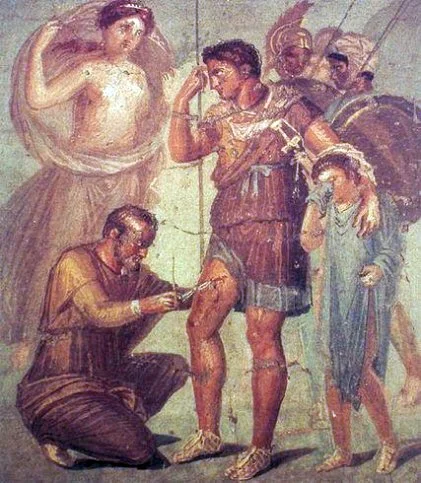

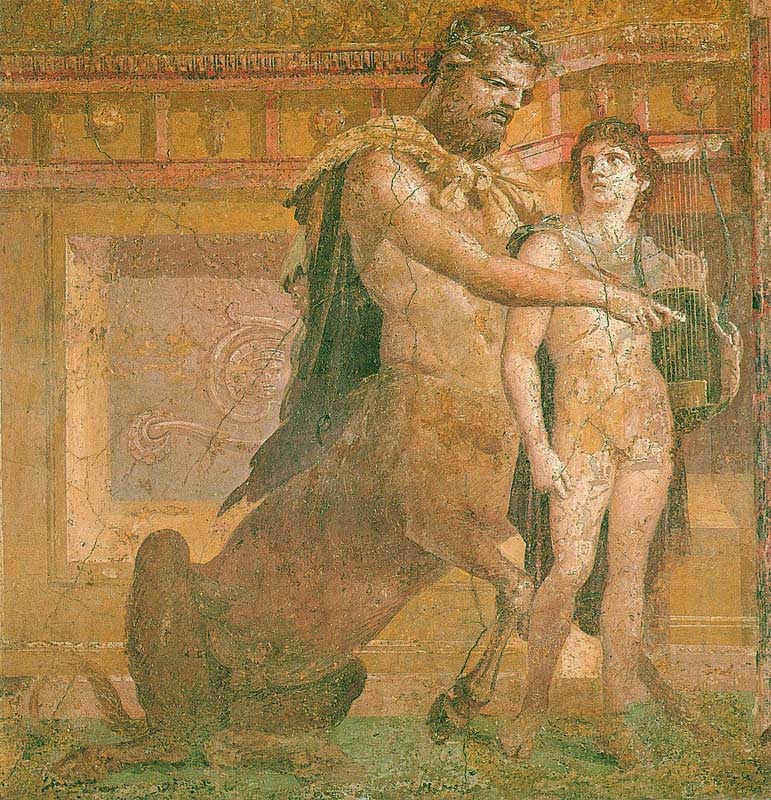

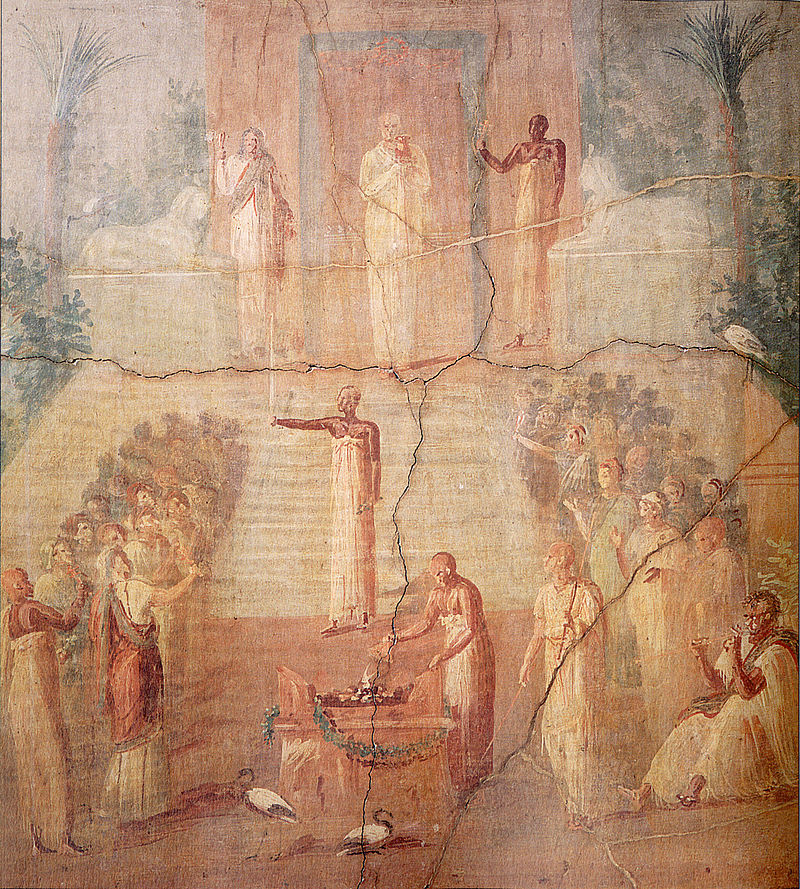

Indeed, the frescoes of the Roman Empire serve as a testament to the enduring influence of Hellenistic culture, particularly evident in their depictions of mythology. Drawing inspiration from Greek mythology, Roman artists skillfully rendered iconic tales and legendary figures on the walls of affluent residences and public spaces.

These mythological motifs not only reflected the intellectual and artistic exchanges between the Roman and Hellenistic worlds but also served as a means of cultural expression and identity for the elite. From scenes of gods and goddesses engaging in epic struggles to narratives of heroic exploits and divine interventions, these frescoes captivated viewers with their vivid storytelling and timeless themes.

2. Iphigenia in Aulis. House of the Tragic Poet, Pompeii.

3. The goddess Flora. Villa Ariadne, Stabiae. (c) ArchaiOptix

4. Europa on the Bull. House of Jason, Pompeii.

5. Perseus and Andromeda. House of the Dioscuri, Pompeii. (c) AlMare

6. Chiron and Achilles. Basilica of Herculaneum.

In addition to providing a window into the mythological realm, Roman frescoes offer a fascinating glimpse into the daily lives of ancient Romans. Through detailed depictions of food, clothing, activities, and the surrounding natural world, these frescoes offer valuable insights into the customs, habits, and preferences of Roman society. Scenes of banquets and feasts showcase the culinary delights enjoyed by the elite, revealing their tastes in food and dining etiquette.

Similarly, frescoes portraying individuals engaged in various activities, such as sports, music, and leisurely pursuits, shed light on the recreational pastimes and social gatherings that occupied their time. Furthermore, the inclusion of flora and fauna in these artworks provides valuable information about the natural environment and agricultural practices of the Roman world.

Pompeian Styles

The Pompeian Styles, as delineated by August Mau, have provided invaluable insights for archaeologists in dating Roman structures containing frescoes, particularly those unearthed in Pompeii. These four distinct periods, spanning from the Roman Republican to the Imperial periods, offer a chronological framework for understanding the evolution of Roman fresco painting.

The first two styles, incrustation and architectural, emerged during the Republican era and are characterized by their relatively simple compositions and motifs. In contrast, the ornamental and intricate styles, which flourished during the Imperial period, exhibit greater sophistication and complexity in design and execution. While each style possesses its own unique characteristics, there is a discernible progression and interplay of elements from earlier styles evident in the later ones.

First Style

The First Style, known as the encrustation style, flourished from 150-80 BC and is distinguished by its imitation of marble-lined walls using shiny stucco decoration. This technique aimed to create the illusion of luxurious and expensive materials without the cost associated with genuine marble. The final effect was achieved through meticulous attention to detail, with a variety of colors meticulously inserted into different partitions. These colors were strategically employed to simulate the appearance of smooth or rusticated paintings, enhancing the overall aesthetic appeal of the interior space.

Second Style

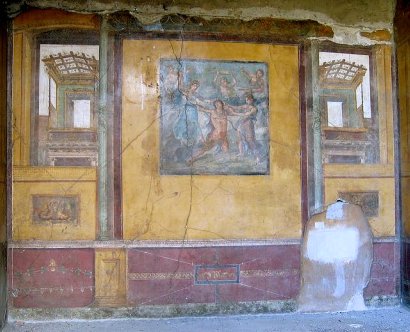

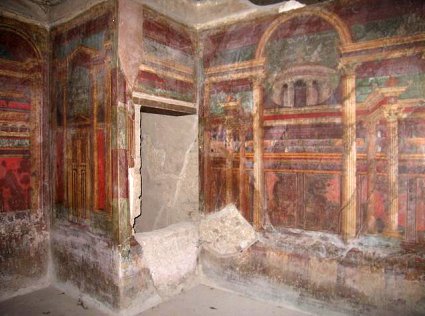

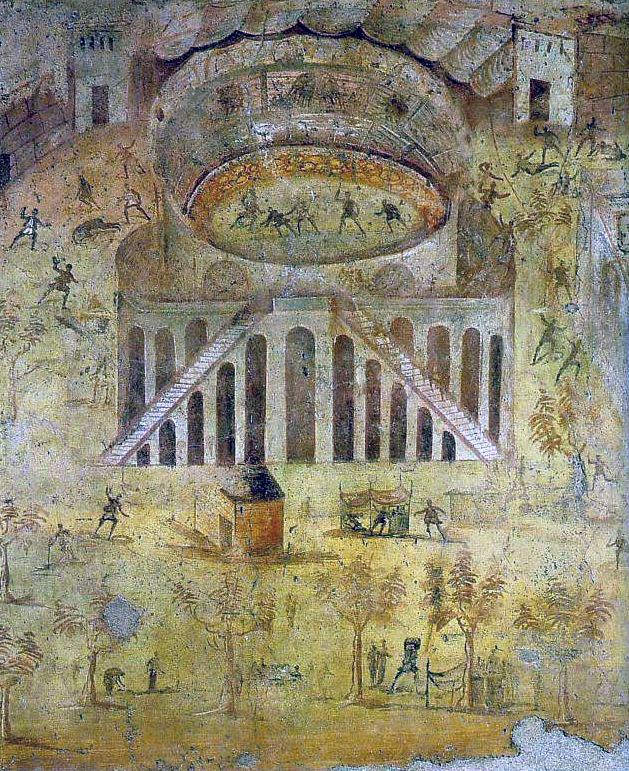

The Second Style, also known as the architectural style, marks a significant departure from the enclosed spaces of the First Style, creating the illusion of expansive vistas and open landscapes within the confines of interior walls. Flourishing between 80 BC and 14 AD, this style introduced a revolutionary approach to fresco painting, employing architectural elements to extend the visual space of the room into imaginary landscapes.

Unlike the earlier encrustation style, which primarily focused on imitating marble patterns, the Second Style utilized perspective techniques to achieve a sense of depth and three-dimensionality. Walls were adorned with elaborate architectural compositions, featuring columns, colonnades, and doorways arranged to create the illusion of depth and distance.

These architectural elements served as frames for larger mythological, heroic, or religious scenes depicted in the central panels, while smaller panels featured intricate details such as ornamental motifs or additional architectural elements. The overall effect was highly theatrical, suggesting a newfound appreciation for dramatic and scenographic presentation influenced by theatrical aesthetics.

Third Style

The Third Style, prevalent until the year 62 AD, represents a departure from the architectural motifs and spatial illusions of the previous styles, opting instead for a more decorative approach that emphasizes flatness and surface ornamentation. In this style, architectural elements such as columns, balustrades, and architraves are rendered in a flattened manner, serving primarily as ornamental elements rather than structural features. Columns are elongated and used as frames for large figure paintings set against plain colored backgrounds. The overall composition loses depth, with landscapes reduced to miniature vignettes set against monochromatic backgrounds, often in shades of sea-green and golden yellow.

This style is often referred to as pseudo-Egyptian due to the incorporation of Egyptian motifs and decorative elements, such as lotus flowers, rosettes, and colored fillets. A distinctive band running along the skirting features still-life scenes, depicting gardens with bulrushes and elegant birds in various poses. Large-scale wall decorations inspired by lush gardens, complete with trees, fountains, pools, and birds in flight, are also characteristic of this period. These elements contribute to the overall ornamental richness of the Third Style, reflecting a synthesis of Egyptian influences and Roman artistic sensibilities.

Fourth Style

The Fourth Style, employed from the earthquake of 62 AD until the destruction of the town in 79 AD, is often referred to as the ornamental style due to its focus on creating elaborate decorative compositions across entire walls. In this style, architectural elements lose their grounding in reality and are transformed into fantastical designs, characterized by excessive ornamentation and intricate details. Bas-relief stucco work, reminiscent of the Second Style, is frequently utilized to enhance the decorative effect. Figure paintings, if present, are smaller in scale or may be entirely absent, replaced by formal subjects often inspired by philosophical or exotic themes.

This style reflects a display of wealth and sophistication, particularly evident in the homes of affluent merchants in Pompeii prior to the catastrophic events. Many scholars believe that the artistic tendencies of the Fourth Style were influenced by the opulent designs found in the Domus Aurea, Nero’s imperial palace in Rome. The adoption of these grandiose decorative schemes served as a testament to the social status and cultural aspirations of Pompeii’s elite, showcasing their affinity for luxurious and fashionable artistic trends of the time.