Sharks come in all shapes and sizes, here in the UK we are lucky to play host to some of the largest, rarest and fastest species in the world! With at least 21 species to be found right off British shores all year round, and plenty more migrants, an encounter with one of these beautiful creatures would be a very exciting and memorable day indeed.

Sharks in the UK vary from the small velvet belly (Etmopterus spinax), growing to a whopping 60cm, all the way to the largest shark in British waters and second largest fish in the world; the charismatic basking shark.

I think its important we stop for a moment before delving into this weeks “Secret lives of British coasts” and let that sink in… One of the oceans giants, existing for over 30 million years, can be seen just offshore in the UK every year!

So lets delve into the secret world of the basking shark.

Latin name: Cetorhinus maximus (meaning: great whale nose)

Common name: Basking shark

Stats:

Lifespan: 50 years

Weight: up to 7 tonnes

Swim speed: 2.5 – 4mph

Maximum total length: 12 – 15m (average: 9.8m)

Maturity: Males- 4-5m (age 12-16), Females- 8- 9.8m (age 18)

Gestation: 12 – 36 months

Size at birth: Unknown (smallest known free-living individual: 1.7m)

Seen in UK: May – late October

Only member of the family: Cetorhinidae

Adaptations:

Sharks have a huge variety of adaptations that has allowed them to thrive for over 400 million years. From skeletons made of cartilage to electroreception, and even skin covered in denticles (tiny teeth).

Basking sharks have 5 enormous gill slits that almost encircle the entire head. These overdeveloped dermal denticle gill rakers allow them to filter vast quantities of plankton from the water.

Although filter-feeders, basking sharks retain minute hooked teeth in rows of 200 in each jaw. Those in the front are small and triangular, whereas the teeth at the sides are more conical and slightly recurved, however they serve little purpose in feeding.

Accounting for upto 25% of its body weight, the large high squalene liver allows the shark to maintain neutral buoyancy in the water.

Unlike most sharks, basking sharks have very limited countershading camouflage. Their dorsal and ventral surfaces are almost uniformly coloured brown unlike most sharks are grey/blue on the dorsal surface and white on the ventral surface. This could be due to the food basking sharks feed on; zooplankton are poor swimmers due to the perceived increased density of water experienced by smaller organisms.

Distribution:

Basking sharks are a global species found in boreal and temperate waters near the coast and further offshore.

To spot one of these enigmatic creatures in the UK there are a few ‘hot spots’ where your chances of an encounter are greatly improved. The southwest (in particular Cornwall), off the Isle of Man, western Scotland (especially the outer Firth of Clyde), and the north of Ireland are all great places to spot a basking shark, and plenty of other wildlife too!

Feeding:

The basking shark is one of the three types of filter-feeding sharks, the other two being the megamouth and whale shark. However unlike the other two species, basking sharks are passive feeders, filtering food out of the water as they swim with their mouths agape.

Although the second largest fish in the world, like the blue whale, basking sharks feed on some of the smallest inhabitants of our oceans. They feed on zooplankton (microscopic creatures that drift with the current), prey includes decapod larvae, fish eggs, deep water oceanic shrimp and copepods, in particular the adult copepod Calanus helgolandicus.

As basking sharks cruise around with their iconic mouths open up to a massive 1.2m wide, filtering 1.5 million liters of water an hour! Swimming with their huge cavernous mouths open and gills distended, plankton is trapped on their unique gill rakers and ingested when the mouth is periodically closed. This huge volume of water fills basking sharks stomachs with an average half a ton of food.

As passive feeders basking sharks maximize their food intake by foraging in the most profitable areas via following zooplankton gradients. They actively select high-density areas of large zooplankton along thermal fronts. The sharks can continue to forage in rich zooplankton areas for up to 27 hours following the plankton hotspot for over 500km.

Behaviour:

If your lucky enough to spot a basking spark, you may even witness that most rare of behavior; the breach. Breaching in basking sharks could be to dislodge parasites, however the energetic cost of breaching makes this unlikely. As with most displays of strength and prowess, breaching is likely a courtship display of fitness and receptivity to mating.

Basking sharks are often found in small groups, however on some rare occasions they are seen in huge aggregations swimming together in one direction.

Migration:

Basking sharks undertake short scale local migrations such as moving from the English Channel up to Scottish waters here in the UK.

These sharks have also been shown to undertake long transoceanic migrations of over 9000km. One shark was tracked migrating from the Isle of Man to Newfoundland, Canada and another individual travelled from New England on the first trans-equatorial migration of its kind to the southern hemisphere.

As well as travelling vast vertical distances, basking sharks also migrate horizontally. Sightings of basking sharks take place during the summer months, which led people to theorise on where they went during the winter. The original theory was these animals hibernated as they lost their gill rakers and therefore were unable to feed.

However these animals don’t lose their gill rakers all at once and instead are utilising deeper feeding areas. They remain within the continental shelf area but spend a greater proportion of time at depths of around 900m, feeding on patchier fronts of zooplankton. This is also indicated by the large proportion of oil typical of deep-water sharks found in the liver.

Reproduction:

Courtship in basking sharks can occur in pairs, groups and even huge schools of up to 100 individuals. Behaviors associated with courtship include breaching, echelon (parallel) and nose-to-tail swimming, rostral contact, pectoral (side) fin biting and nudging. These behaviors have been witnessed taking place in the UK in the southwest between May and July.

Female basking sharks are ovoviviparaous whereby young are born live, however there is no placental connection. Mothers are also oophagous and expend energy producing infertile eggs for the young to feed on after the yolk sac is absorbed.

Gestation lasts 12-36 months with females resting for one year between pregnancies. The estimated length of young at birth is between 150-200cm, however this is based on one anecdotal witnessed birth. Little is know about where baby basking sharks are born and their nursery grounds as they are seldom seen until they are at least 3m in length.

Threats:

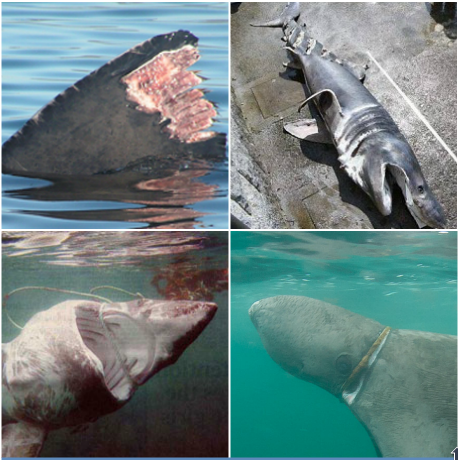

Although now heavily protected, basking sharks were once considered no more than a commodity and were extensively harvested worldwide. The sharks were taken for their oil rich liver to tan leather and industrial processes, fins for shark fin soup, meat for human consumption, skin for leather and to produce fishmeal.

In the UK alone approximately 105,000 individuals were killed between 1946 and 1995, which is a devistating loss for a slow growing species which is extremely vulnerable to overfishing.

Commercial fishing of these sharks may have ceased in the UK, yet sadly they still face many more negative impacts from human activity. Like the majority of marine species basking sharks face the threat of bycatch in fishing nets, entanglement in ghost nets, ingestion of micro plastics (up to 13,110 items per day), boat strikes, disturbance from water users, habitat loss, chemical pollution and climate change.

Will climate change lead to shifts in the number or distribution of basking sharks in the UK? Over the last 5 decades there has been an increase and northward movement of warm water plankton and a decline in cold-water species. These changes are altering the seasonality and abundance of preferential food as basking sharks follow areas rich in cold-water zooplankton, therefore it is not unlikely the distribution of the sharks will also move northward.

Conservation:

Due to past exploitation, subsequent declining populations and the ongoing threats they face from human activity, basking sharks have been granted full legal protection in the UK since 1998. This legislation includes:

UN Convention on the Law of the Sea – Annex I

CITES – Appendix II

IUCN Red List – listed as vulnerable

UK Biodiversity Action Plan – priority species

EU Common Fisheries Policy – prohibited species

Convention on Migratory Species – Appendices I & II

OSPAR – list of threatened and/or declining species

Wildlife & Countryside Act

Countryside Rights of Way Act

There is no doubt basking sharks are amazing creatures and a desire to see one in the wild is something we all share. If you are lucky enough to encounter a basking shark then please follow the code of conduct laid out by the Shark Trust for all water users.

This ensures you have a fun and safe encounter, but most importantly it protects the shark(s) so they can continue their natural activities undisturbed.

Get involved:

Record any and all shark sightings

Record collisions, entanglement and harassment of sharks

Live or dead stranding’s

References:

Compagno, L.J.V., 1984. FAO Species Catalogue. Vol. 4. Sharks of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Part 1 – Hexanchiformes to Lamniformes. FAO Fish. Synop. 125(4/1):1-249. Rome: FAO. (Ref. 247)

Fossi, M., Coppola, D., Baini, M., Giannetti, M., Guerranti, C., Marsili, L., Panti, C., de Sabata, E. and Clò, S. (2014). Large filter feeding marine organisms as indicators of microplastic in the pelagic environment: The case studies of the Mediterranean basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) and fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus). Marine Environmental Research, 100, pp.17-24.

Rus Hoelzel, A., Shivji, M., Magnussen, J. and Francis, M. (2006). Low worldwide genetic diversity in the basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus). Biology Letters, 2(4), pp.639-642.

Sims, D.W. & Quayle, V.A. (1998) Selective foraging behaviour of basking sharks on zooplankton in a small-scale front. Nature 393, 460-464.

Vas, P. (1991). A field guide to the sharks of British coastal waters. Field studies council, 7, pp.651-686.